FEATURE:

Groovelines

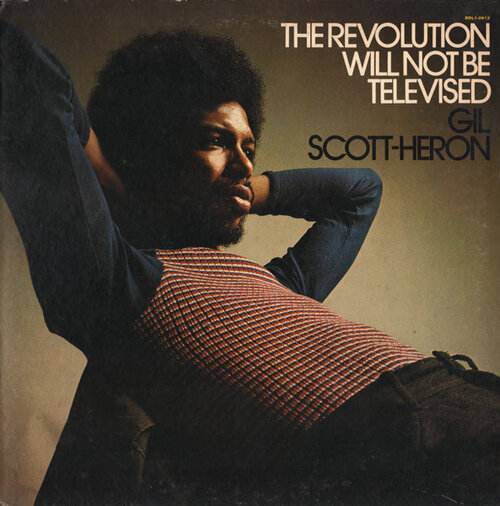

Gil Scott-Heron - The Revolution Will Not Be Televised

___________

I want to bring in a few articles…

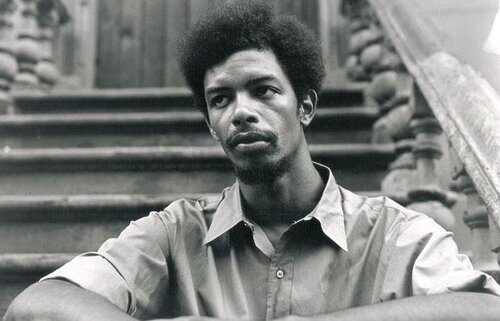

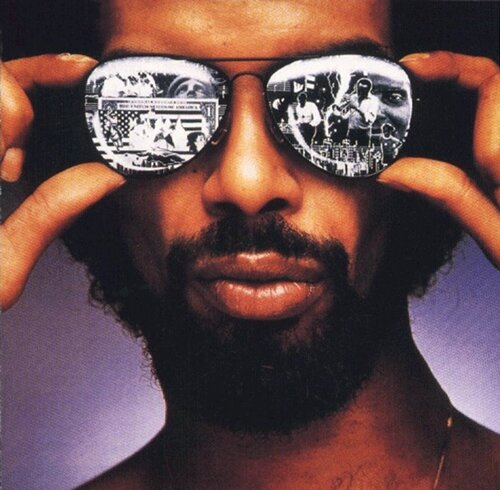

regarding this song, as I can not do it true justice on my own. The Revolution Will Not Be Televised is a glorious by Gil Scott-Heron. Scott-Heron first recorded it for his 1970 album, Small Talk at 125th and Lenox. A re-recorded version, with a full band, was the B-side to Scott-Heron's first single, Home Is Where the Hatred Is (from his album Pieces of a Man (1971). As the album turns fifty very soon, I wanted to spotlight a truly incredible piece of music. The song's title was originally a popular slogan among the 1960s’ Black Power movements in the United States. The song was inducted to the National Recording Registry in 2005. I am going to source from a few articles that tell us the story of The Revolution Will Not Be Televised and why it remains so important and powerful. If you have not heard the Pieces of a Man album, I would advise you to seek it out. This is what AllMusic said when they tackled it:

“Gil Scott-Heron's 1971 album Pieces of a Man set a standard for vocal artistry and political awareness that few musicians will ever match. His unique proto-rap vocal style influenced a generation of hip-hop artists, and nowhere is his style more powerful than on the classic "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised." Even though the media -- the very entity attacked in this song -- has used, reused, and recontextualized the song and its title so many times, the message is so strong that it has become almost impossible to co-opt. Musically, the track created a formula that modern hip-hop would follow for years to come: bare-bones arrangements featuring pounding basslines and stripped-down drumbeats. Although the song features plenty of outdated references to everything from Spiro Agnew and Jim Webb to The Beverly Hillbillies, the force of Scott-Heron's well-directed anger makes the song timeless. More than just a spoken word poet, Scott-Heron was also a uniquely gifted vocalist. On tracks like the reflective "I Think I'll Call It Morning" and the title track, Scott-Heron's voice is complemented perfectly by the soulful keyboards of Brian Jackson. On "Lady Day and John Coltrane," he not only celebrates jazz legends of the past in his words but in his vocal performance, one that is filled with enough soul and innovation to make Coltrane and Billie Holiday nod their heads in approval. More than three decades after its release, Pieces of a Man is just as -- if not more -- powerful and influential today as it was the day it was released”.

Not to mangle a great piece of writing, but Medium documented the origins of The Revolution Will Not Be Televised and the events leading up to its creation. The beginnings occurred at a time of racial struggle and injustice in the United States:

“When Gil returned to campus in September of 1969, the school was on the verge of revolt. As a rural school, too far away from urban unrest, Lincoln University didn’t experience the explosive rage blowing up on other black campuses such as Howard University or Morgan State. But there was plenty of anger directed at the conservative school administration, which looked down on political demonstrations and some of the free-form creativity taking place on campus. The school had started admitting female students only the year before, and some of the older students and faculty were still resentful at the changes taking place on campus. But Gil and his friends kept pushing for even more change.

Among them was Carl Cornwell, a student who occasionally jammed with the Black and Blues, a band fronted by Gil. He was also a member of a jazz quintet that played a lot of contemporary music by Herbie Hancock and McCoy Tyner. Called the Harrison Cornwell Limited after Cornwell and trumpeter Joe Harrison, the group had originally included Brian Jackson, until Gil snatched him away to play with the Black and Blues. Cornwell, whose father taught at Lincoln, grew up in town and was imbued with the school’s pride and heritage. But once he became a student, he saw firsthand that the college was lacking essential services and wasn’t responsive enough to the needs of students.

At midnight one Friday in November 1969, at the end of a rehearsal, Cornwell’s group was packing up their instruments when drummer Ron Colbert started having an asthma attack and his inhaler wasn’t helping him catch a breath. The group walked to the school infirmary but it was closed. So they took Ron back to his room. By the time the ambulance arrived, it was too late. “He died in my arms,” remembers Cornwell. “I’ll never forget it.”

The tragedy could have been avoided if the infirmary had been staffed and open around the clock. Colbert’s death brought to a head some issues that had been simmering for years: Gil’s neighbor in his freshman dorm had died of an aneurism that had gone untreated after being detected, and several students had had their medical problems misdiagnosed by the campus doctor.

When Gil returned on Sunday night from a weekend in New York City, he quickly found out about Ron’s death and decided to take action, demanding adequate medical facilities. The student body united around the demands, especially after the administration started to claim that Colbert may have been getting high, though there was no evidence that the young man used drugs.

I would advise people to check out the full article. I wonder whether there will ever be a T.V. series or short around The Revolution Will Not Be Televised; one that uses the song as a central focus and features events in politics and society from late-1960s America. Perhaps there has been something produced; I think the political events of the late-1960s and how they resonated with people like Scott-Heron is fascinating.

“By 1970, Gil had written a few dozen poems that worked as song lyrics, most of them political and social commentary such as “Brother,” “Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul?” and one song that will define him forever. That spring, he and Brian and some friends were sitting around watching TV one night in one of the dorms when a news report came on about a demonstration. The newscasters started talking about how many people were taking part. “We said, ‘People ought to get out there and do something; the revolution won’t be televised,” Gil later recounted. “A cat said, ‘You ought to write that down.”

Over the next few weeks, Gil started writing down lyrics in his notebook, and he and Brian started paying more attention to what was actually being shown on television. They noticed the commercials, and the friends commented to each other on the insidiously persuasive power of ads for everything from toilet cleaner to breakfast cereal. The contrast between the commercials and the demonstrations in the streets could not have been more glaring: one was on TV, and the other was live. When he was finished writing, he titled the poem “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”.

Whether you consider The Revolution Will Not Be Televised to be an epic performance poem or a song, I feel it is one of the most potent and fascinating recordings in history.

I want to source from an article from Open Culture. We get a n interview exert from Gil Scott-Heron where he discussed The Revolution Will Not Be Televised:

“One might think Scott-Heron’s classic spoken-word testament “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” speaks for itself by now, but it still creates confusion in part because people still misconstrue the nature of the medium. Why can’t you sit at home and watch journalists cover protests and revolts on TV? If you think you’re seeing “the Revolution” instead of curated, maybe spurious, content designed to tell a story and gin up views, you’re fooling yourself.

But Scott-Heron also had something else in mind—you can’t see the revolution on TV because you can’t see it at all. As he says above in a 1990s interview:

The first change that takes place is in your mind. You have to change your mind before you change the way you live and the way you move. The thing that’s going to change people is something that nobody will ever be able to capture on film. It’s just something that you see and you’ll think, “Oh I’m on the wrong page,” or “I’m on I’m on the right page but the wrong note. And I’ve got to get in sync with everyone else to find out what’s happening in this country.”

If we realize we’re out of sync with what’s really happening, we cannot find out more on television. The information is where the battles are being fought, at street level, and in the mechanisms of the legal process. “I think that the Black Americans are the only real die-hard Americans here,” Scott-Heron goes on, “because we’re the only ones who’ve carried the process through the process…. We’re the ones who marched… we’re the ones who tried to go through the courts. Being born American didn’t seem to matter.” It still doesn’t, as we see in the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and so many before them, and in the grievous injuries and deaths from unconstitutional, military-grade police escalations nationwide since”.

I am going to wrap up soon but, just before, I wanted to highlight an essay by Marcus Baram. It helps answer misconceptions about the song and why The Revolution Will Not Be Televised is such a timeless poetic work – a mandate that could be applied to society today and how there is still huge inequality:

“In the song, Gil recites advertising slogans for some of America’s most famous brands-- Coca-Cola, Listerine, Hertz, Dove, Exxon--totems of the consumer culture of the 1950s and 1960s which had inculcated themselves into the country’s mythology and folklore. And he name-checks popular TV shows and movie stars—“Green Acres,” “The Beverly Hillbillies,” Natalie Wood, Steve McQueen--the demigods of America’s popular culture. His voice dripping with sarcasm, Gil mocks their triviality and insignificance because when the revolution comes, “black people will be in the street looking for a better day,” because “there will be no highlights on the 11 o’clock news.” He continues: The revolution will not go better with Coke The revolution will not fight the germs that cause bad breath The revolution WILL put you in the driver's seat The revolution will not be televised WILL not be televised, WILL NOT BE TELEVISED The revolution will be no re-run brothers The revolution will be live Long before he stepped into a recording studio, Gil already saw the poem as a song, a classic 12-bar blues track. And the next year, when he worked on his first album, “Small Talk at 125th and Lenox,” he recorded the lyrics to the poem, accompanied by congas and bongo drums, in front of a small group of friends sitting on folding chairs in a studio in midtown Manhattan.

It was later re-recorded with a full band, including his pal Brian Jackson on flute, as the B-side to his 1971 single, “Home Is Where The Hatred Is” for an album produced by Bob Thiele, who had also worked with John Coltrane and poets like Jack Kerouac. The song and the album were an early example of a creative work going viral, decades before the launch of Twitter and Facebook. It didn’t get much airplay on radio, due to its incendiary lyrics, but it spread by word of mouth in black neighborhoods around the country, in campus coffee shops and nightclubs in West Philadelphia, Harlem, Watts, Chicago’s South Side, and Atlanta. Poet Nikki Giovanni remembers seeing Gil perform the song at a store in Harlem and feeling encouraged that his voice--strong, black, political, poetic--was out there, shaping the minds of his generation. The song became an anthem for a revolutionary era, honored as one of the top 20 political songs in history, and compared to Allan Ginsberg’s “Howl” and Bob Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” Later, it became recontextualized and distorted into a message that became the medium again as a slogan on T-shirts and endless headlines that misunderstood the original meaning of the song. In a bitter irony, Gil himself allowed the song to be coopted and used in a TV ad for Nike back in 1994, a decision he always regretted. At the time he was battling a drug addiction and desperate for money, so he accepted director Spike Lee’s request to let rapper KRS-One transform the lyrics into an ode to basketball to help sell the sneaker giant’s new Air Jordans. Until his death in 2011, Scott-Heron was alternately proud of the song’s power and resonance but also frustrated by the way its meaning had been consistently misunderstood by many listeners who took the song’s title literally, that the revolution won’t be aired live on television. But what Gil meant in the song, and it’s obvious from hearing the lyrics, is that you have to be active, you can’t be a passive participant in the revolution. When the revolution happens, you’re going to have to be in the streets. If you want to make change in society, you have to get off your ass and take action. You just can’t sit on your couch and watch it on TV”.

Just ahead of the fiftieth anniversary of Gil Scott-Heron’s Pieces of a Man album (it was recorded in April and released later in the year), I wanted to dissect an incredible musical work. It is sad that, in some ways, society and relations have not progressed since the late-1960s; how there is still such injustice. Of course, The Revolution Will Not Be Televised is not only inspired by racial injustice but, as we are still living in a time where there is such horror and a lack of progression, one cannot help but extrapolate various words and lines from the track and apply them to the here and now. The Revolution Will Not Be Televised is a remarkable work that, over fifty years since its introduction…

MOVES and inspires all the senses.