FEATURE:

A Mid-Sixties Masterpiece

Bob Dylan at Eighty: The Majesty of Blonde on Blonde

___________

IT is quite timely…

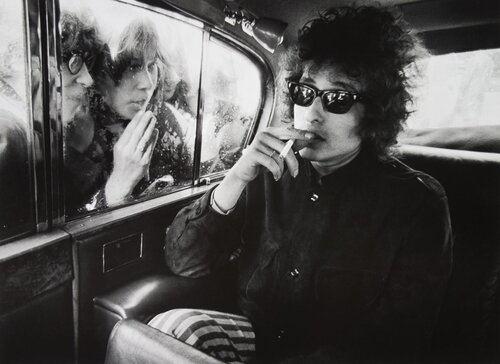

IN THIS PHOTO: Bob Dylan in London in 1966/PHOTO CREDIT: Barry Feinstein

that I mention Bob Dylan’s seventh studio album, Blonde on Blonde, ahead of the master’s eightieth birthday on 24th May. It was released as a double album on 20th June, 1966 by Columbia Records – its approaching fifty-fifth anniversary is one to celebrate. Recording sessions startyed in New York in October 1965. There were numerous backing musicians, including members of Dylan's live backing band, the Hawks. Only one track from the sessions made its way onto Blonde on Blonde: the terrific One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later). Taking a different approach producer Bob Johnston, Dylan, keyboardist Al Kooper, and guitarist Robbie Robertson relocated to the CBS studios in Nashville, Tennessee. It was then that the remaining tracks were laid down and completed. I think Blonde on Blonde is one of the great Dylan masterpiece. It arrived during a golden run of albums; the final of a trilogy of incredible albums from that time - Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited were released in 1965. Not only is Blonde on Blonde one of the best albums ever; it was one of Rock’s first double albums. Dylan’s lyrics range from the personal to the widescreen and fantastical. In terms of the compositions, I think it was Dylan’s broadest and most wide-ranging to that point. After introducing the electric guitar into his music from 1965, he was moving further away from the acoustic sound of his earliest albums. Three of my favourite Dylan songs appear on Blonde on Blonde. Visions of Johanna, I Want You and Just Like a Woman are classics. In fact, each of the fourteen tracks is superb and without fault! I am going to bring in a couple of reviews and articles regarding Blonde on Blonde – finishing with a section about the album’s legacy and importance.

Not to mangle it too much, but Rolling Stone produced a great article in 2016 ahead of the fiftieth anniversary of an iconic album from a songwriting genius. I am interested in the early sessions and how things started to come together in terms of pace and productivity:

“I was going at a tremendous speed… at the time of my Blonde on Blonde album,” Bob Dylan told Rolling Stone editor and publisher Jann S. Wenner in 1969. On Blonde on Blonde, all the tension and angst of Highway 61 Revisited and Bringing It All Back Home were blown wide open to reveal pure freedom. It’s rock’s first double-album monument, where the distance between Dylan’s imagination and his music collapsed entirely: “The closest I ever got to the sound I hear in my mind,” he famously said, “that thin, that wild mercury sound.” With its chain-lightning mix of rock & roll, novelty music, surrealist ballads, Chicago blues and psychedelic country, its peels of lyrical invention and epic song lengths, Blonde on Blonde might seem like the kind of work that involved long-term contemplation.

In fact, most of the album was knocked out between stints on the road during a historically intense bout of touring. In the fall of 1965, Dylan wanted to continue pushing his new sound, and tour with an electric band. A decision was made to split a series of upcoming concerts between an acoustic set and a plugged-in performance. At the suggestion of his manager Albert Grossman’s secretary, Dylan checked out Canadian band the Hawks, who had cut their teeth backing rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins. Dylan was especially impressed by Robbie Robertson, the band’s 22-year-old guitarist, and asked the Hawks to play two shows, one in New York and one in L.A. At the New York show, held in front of a crowd of 14,000 at the Forest Hills tennis stadium in Queens, fans sat patiently through Dylan’s acoustic songs and then commenced booing during his electric set (some people sang along to “Like a Rolling Stone” and then booed when it was over). After they completed their West Coast date, the Hawks (soon to be renamed the Band) were hired for a year of shows that began in Texas in September 1965.

That October, just as the tour was beginning, Dylan and the Band went into Columbia Studios in New York and recorded the single “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?” a curt blast of “Like a Rolling Stone”-style acrimony Dylan was so pleased with that he once kicked folk-scene grandee Phil Ochs out of a limo for saying he didn’t like it. Surprisingly, though, more attempts by Dylan and the Band throughout the fall and winter produced only one song that made it onto Blonde on Blonde, “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later),” a swirling haymaker that took 24 takes and had to be finished with the help of other musicians. “Oh, I was really down,” Dylan told writer Robert Shelton.

Salvation came from a surprising place. The previous summer, during the end of the at-times-difficult sessions for Highway 61 Revisited, producer Bob Johnston had introduced Dylan to multi-instrumentalist Charlie McCoy, a seasoned musician from Nashville who’d played with everyone from Elvis to Perry Como. After McCoy sat in on the recording of “Desolation Row,” Johnston suggested Dylan might like recording in Nashville. “See how easy that was,” Johnston said”.

When Dylan arrived in Nashville with his new wife, Sara, and their one-month-old son, Jesse, he had a few songs ready to go.” The elegant “Fourth Time Around” was a direct (albeit never acknowledged) reference to the Beatles’ Dylanesque classic “Norwegian Wood,” with the lyrics “I never asked for your crutch/Now don’t ask for mine” possibly serving as a warning to John Lennon to stop ripping him off. “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat” was a hilarious snatch of 12-bar Chicago blues that has long been rumored to be about Edie Sedgwick, reigning starlet of Andy Warhol’s Factory scene, who Dylan had been spending time with recently (when asked about the song in 1969, Dylan said he “mighta seen a picture of one in a department-store window”).

The album’s first session would produce the epochal “Visions of Johanna,” which Dylan first debuted in 1965 at a Berkeley concert attended by Allen Ginsberg and Joan Baez (who insisted the song was about her). With Kooper’s organ and Robertson’s trebly guitar shadowing Dylan’s lyrics, which go on for five image-stuffed verses, the song turns a recollection of a hazy New York night into a liquid meditation on carnal obsession and spiritual desire. At seven minutes long, it also suggested this wasn’t going to be just another series of recording dates.

“It was really … ‘far out’ would be the term I would have used at the time,” said Bill Aikins, who played keyboards on the song. “And still today, it was a very out-there song.” As Dylan later said, “I’d never done anything like it before.”

The song set the tone for the rest of the sessions. Dylan got down to writing new songs and called the musicians in when it was time to record. For the crack team of players, this was an entirely new experience. Accustomed to Nashville’s sharp standards of professionalism and tight budgets, where a musician was rewarded for working quickly and the most efficient players might record a song an hour, they now found themselves being paid to be on call waiting for genius to strike. “There were some days when he would sit in the studio for six hours and work on the lyrics,” says Kooper. “We ended up getting there at 12 noon and going home at, like, five or six in the morning. We’d get there at 12 and wouldn’t record anything until four or five”.

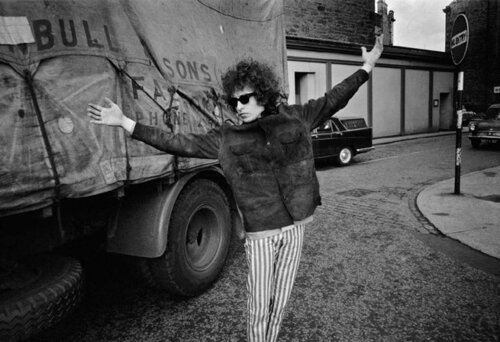

IN THIS PHOTO: Bob Dylan in Scotland in 1966/PHOTO CREDIT: Barry Feinstein

When they were summoned, the songs that awaited were unlike anything they’d ever played on. The day after recording “Visions of Johanna,” Dylan laid down another landmark epic, “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands,” which ended up stretching out past 10 minutes in the studio and took up the entire final side of Blonde on Blonde. An ode to Sara Dylan, it “started out as a little thing,” as Dylan later recalled, “but I got carried away somewhere down the line.”

“We started ‘Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands,’ a 14-minute ballad, at 4 a.m.,” McCoy recalls. “And concentration is tough at four in the morning, when you’ve been up all night, waiting to play, and nobody wanted to be that guy that messed up. But we did it, and then after that, everything went much smoother.”

With his creativity peaking, Dylan began entertaining the idea that the album might become a double LP. He left Nashville for some more concert dates and returned in mid-March to finish the record. The songs recorded during the March session were shorter and flowed faster than ever, with Dylan working on a piano in his hotel room and Kooper playing musical director, taking Dylan’s ideas to the session musicians to prep them so that when Dylan finally arrived with the finished song they’d be ready”.

I think it is worth bringing in a critical review for Blonde on Blonde. In their write-up, this is what AllMusic remarkable about one of Bob Dylan’s most-celebrated albums:

“If Highway 61 Revisited played as a garage rock record, the double album Blonde on Blonde inverted that sound, blending blues, country, rock, and folk into a wild, careening, and dense sound. Replacing the fiery Michael Bloomfield with the intense, weaving guitar of Robbie Robertson, Bob Dylan led a group comprised of his touring band the Hawks and session musicians through his richest set of songs. Blonde on Blonde is an album of enormous depth, providing endless lyrical and musical revelations on each play. Leavening the edginess of Highway 61 with a sense of the absurd, Blonde on Blonde is comprised entirely of songs driven by inventive, surreal, and witty wordplay, not only on the rockers but also on winding, moving ballads like "Visions of Johanna," "Just Like a Woman," and "Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands." Throughout the record, the music matches the inventiveness of the songs, filled with cutting guitar riffs, liquid organ riffs, crisp pianos, and even woozy brass bands ("Rainy Day Women #12 & 35"). It's the culmination of Dylan's electric rock & roll period -- he would never release a studio record that rocked this hard, or had such bizarre imagery, ever again”.

Before rounding off with a Wikipedia article that outlines the legacy and popularity of Blonde on Blonde, there is another article that I want to source from. Americana UK looked back on Blonde on Blonde in their feature from last year:

“But what about Dylan and Americana? Back in the Sixties practically nobody really spoke, considered, or tried to combine genres into something that currently bears that name. Practically nobody, except Dylan. And that is where one of his (and everybody else’s) masterpieces ‘Blonde on Blonde’ comes in.

No, it is not the fact that it was what quite a few critics considered the third part of his ‘electric’ trilogy, nor that it was one of the first double albums in modern music ( in some countries, Frank Zappa and his Mothers of Invention beat him to the punch with their ‘Freak Out’ album). It is the fact that on this 72-minute epic Dylan actually brought to the main music scene a combination of musical styles that was simply more than just what was named country rock, but moreover an intricate combination that now bears the name(s) of roots music and Americana.

Let’s mention a few facts here. Dylan began writing and demoing the songs that comprise ‘Blonde on Blonde’ at the time when he started rehearsing and playing live with a band that was then called The Hawks, later to become his staple (live) band – The Band. The cooperation came through Robbie Robertson, then Hawks guitarist instrumental on his previous two ‘electric’ albums (‘Bringing It All Back Home’ and ‘Highway 61 Revisited’), but it was also the moment when one of the musicians also instrumental for that electric Dylan sound, keyboardist Al Kooper, decided not to tour live with Dylan anymore. After ‘Blonde on Blonde,’ ‘New Morning‘ was the last studio album on which Kooper was to appear.

The problem was that Dylan and The Hawks gelled so well on stage, but the studio sessions not so much. Of course, that seemed to change when they went into a basement. But Dylan was always a restless character, who kept on immersing practically anything he would hear and liked and shaping it into not just something personal, but also unique and – magical.

To try and revitalize the sessions, then Dylan producer Bob Johnston sent Dylan, Kooper, and Robertson to Nashville, where they were joined by stellar session musicians, harmonica player, guitarist, and bassist Charlie McCoy, guitarist Wayne Moss, guitarist, and bassist Joe South, and drummer Kenny Buttrey. Kooper represented the link with the electric sound, Robertson was shaping himself into the link between rock and roots music, and the seasoned session musicians turned out to be that salt and pepper that gave the album the character of a true combination of rock, roots, country, blues – and you can add a few more genres there easily.

What we get is a set of truly sublime songs, both musically and lyrically. Take, just three as an example. The opening ‘Rainy Day Women No. 12 & 35’ was probably a shock not only to his old folk fans but his relatively newly acquired rock fans. It plays out like a drunken Mardi Gras band walking down the streets of New Orleans at five in the morning (with a piano being pulled on one of the carts), but still being able to keep their composure, while Dylan, in a manner, that only he has, combines and weaves drug and Biblical metaphors into a unified whole.

Or, consider ‘I Want You.’ The session musicians, driven by Wayne Moss’ (later of Area Code 615 and Barefoot Jerry) guitar picking set into a slightly mutated bluegrass groove with Dylan crams in a list of at least seven characters into song’s three minutes.

And then there’s the concluding 11 minutes or so epic ‘Sad Eyed Lady of The Lowlands’. With its cyclical melody, that gains in intensity, Dylan spins an Appalachian -style fairy tale about a mystical woman, whoever she was. And it certainly does sound like Appalachia, but with a timeless quality – there’s no chance any listener can clearly say when this song or any on this album were recorded – in 1966, any decade that followed, or yesterday. A true classic in every sense of that word”.

Many of us know about how good Blonde and Blonde sounds and what its highlights are. This Wikipedia article outlines the cross-pollination of Blonde and Blonde and how it has been celebrated since its release:

“Dylan scholar Michael Gray wrote: "To have followed up one masterpiece with another was Dylan's history making achievement here ... Where Highway 61 Revisited has Dylan exposing and confronting like a laser beam in surgery, descending from outside the sickness, Blonde on Blonde offers a persona awash inside the chaos ... We're tossed from song to song ... The feel and the music are on a grand scale, and the language and delivery are a unique mixture of the visionary and the colloquial." Critic Tim Riley wrote: "A sprawling abstraction of eccentric blues revisionism, Blonde on Blonde confirms Dylan's stature as the greatest American rock presence since Elvis Presley." Biographer Robert Shelton saw the album as "a hallmark collection that completes his first major rock cycle, which began with Bringing It All Back Home". Summing up the album's achievement, Shelton wrote that Blonde on Blonde "begins with a joke and ends with a hymn; in between wit alternates with a dominant theme of entrapment by circumstances, love, society, and unrealized hope ... There's a remarkable marriage of funky, bluesy rock expressionism, and Rimbaud-like visions of discontinuity, chaos, emptiness, loss, being 'stuck'."

That sense of crossing cultural boundaries was, for Al Kooper, at the heart of Blonde on Blonde: "[Bob Dylan] was the quintessential New York hipster—what was he doing in Nashville? It didn't make any sense whatsoever. But you take those two elements, pour them into a test tube, and it just exploded." For Mike Marqusee, Dylan had succeeded in combining traditional blues material with modernist literary techniques: "[Dylan] took inherited idioms and boosted them into a modernist stratosphere. 'Pledging My Time' and 'Obviously 5 Believers' adhered to blues patterns that were venerable when Dylan first encountered them in the mid-fifties (both begin with the ritual Delta invocation of "early in the mornin"). Yet like 'Visions of Johanna' or 'Memphis Blues Again', these songs are beyond category. They are allusive, repetitive, jaggedly abstract compositions that defy reduction."

Blonde on Blonde has been consistently ranked high in critics' polls of the greatest albums of all time. According to Acclaimed Music, it is the 9th most ranked album on all-time lists In 1974, the writers of NME voted Blonde on Blonde the number-two album of all time. It was ranked second in the 1978 book Critic's Choice: Top 200 Albums and third in the 1987 edition. In 1997 the album was placed at number 16 in a "Music of the Millennium" poll conducted by HMV, Channel 4, The Guardian and Classic FM. In 2006, TIME magazine included the record on their 100 All-TIME Albums list. In 2003, the album was ranked number nine on Rolling Stone magazine's list of "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time", maintaining the rating in a 2012 revised list. In 2004, two songs from the album also appeared on the magazine's list of "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time": "Just Like a Woman" ranked number 230 and "Visions of Johanna" number 404. (When Rolling Stone updated this list in 2010, "Just Like a Woman" dropped to number 232 and "Visions of Johanna" to number 413.) The album was additionally included in Robert Christgau's "Basic Record Library" of 1950s and 1960s recordings—published in Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981) - and in critic Robert Dimery's book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die. It was voted number 33 in the third edition of Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums (2000). It was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999”.

Nearly fifty-five years since its release, Blonde on Blonde has moved and blown away so many people! At such a rich and fertile period for Dylan, it is perhaps no surprise he was so ambitious and productive on this double album. Many can argue which Dylan album is the best. I think Blonde and Blonde is right near the top! As the great man turns eighty on 24th May, I wanted to highlight one of his crowning achievements. There is no doubting the fact that Blonde on Blonde is...

A real masterpiece.