FEATURE:

Vinyl Corner

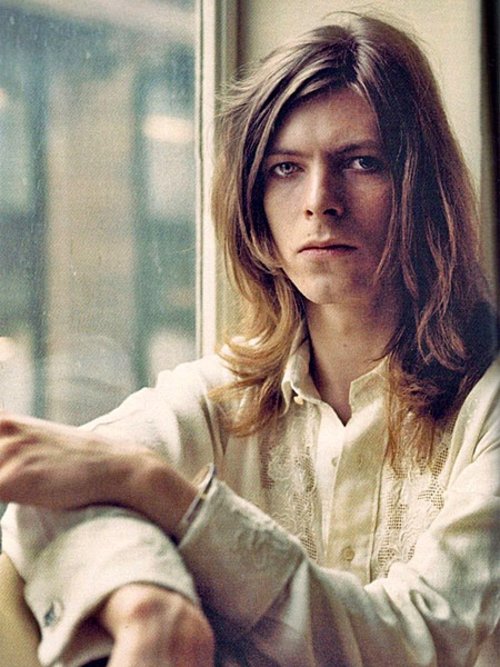

David Bowie – Hunky Dory

___________

NOT that a reason is needed…

to include David Bowie in any feature but, on 17th December, Hunky Dory turns fifty. One of Bowie’s most important albums, it is one that is well worth getting on vinyl. It is an album that contains some of his best songs. It features Changes, Life on Mars?, and Kooks. There are few artists who could complete with Bowie in the 1970s. The incredible run of albums he released in the decade showed he was one of the most innovative and original artists ever! Whereas 1970’s The Man Who Sold the World is a harder and grittier album, Hunky Dory is softer, more melodic and a different direction – Bowie choosing to write on the piano more compared with the guitar for the previous album. I know that there will be a lot of celebration and remembrance of Hunky Dory on its anniversary. It is over five years since we lost David Bowie. He left us with so many genius albums. Hunky Dory ranks alongside his very best. I will source a review of the album – I am yet to find one that is not overwhelmingly positive – that shows what a pioneer Bowie was. Before that, on its forty-ninth anniversary, LOUDER produced a lengthy and detailed feature about how Hunky Dory was made and why it was such an important release for Bowie. I have selected a few sections that interested me. Bassist Trevor Bolder and drummer Mick Woodmansey (and others) provided their recollections and memories:

“Sessions began at Trident Studios in London’s Soho in early June 1971. In the world outside, US president nixon ended a 21-year-old trade embargo on China; Russia launched the Soyuz 11 craft for the first-ever rendezvous with a space station; Frank Sinatra announced his retirement; and topping the pop chart in Britain was Tony Orlando & Dawn’s Knock Three Times.

Inside Trident, however, none of that registered. Working from 2pm to midnight, Monday to Saturday, with quick breaks for tea, sandwiches and the occasional bottle of wine, the band were swept up in a colourful world of bipperty-bopperty hats, Garbo’s eyes and homo superiors (the album’s recurring theme of children ch-ch-changing into enlightened beings was influenced by Bowie’s love of the occult writings of Aleister Crowley, and sci-fi novels by Arthur C Clarke).

Bolder recalls the excitement: “Hunky Dory was the first recording session I ever did in my life, and just to be in a studio was amazing. Our approach was very off-the-top-of-our-heads. We’d go in, David would play us a song – often one we hadn’t heard – we’d run through it once and then take it. no time to think about what you’re going to play, you’d have to do it there and then. In some respects it’s nerve-racking, but it gives a certain feel. If you play a song too many times in the studio it can become stale, and I think David wanted to capture the energy of it being on the edge.”

Woodmansey agrees: “There was incredible pressure in getting a track recorded right. Many times, we’d go in with a track to record, and at the last minute David would change his mind and we’d do one we hadn’t rehearsed! We would be panicking, as he didn’t like doing more than three takes to get it. nearly every track I recorded with David was first, second or third take, usually second. he knew when a take was right.”

This was a change from the sessions for the previous album, where Bowie was reportedly distracted and undisciplined. Tony Visconti later complained that during the recording of The Man Who Sold The World David had spent more time in the lobby cuddling with Angie than worrying about finishing the tracks. But the Bowie on Hunky Dory was a man with a mission

Ken Scott: “With David, unlike the Beatles sessions, it was very much him knowing what he wanted right from the get-go. I think he knew all along what was going to happen, but he didn’t always tell you. you had to be ready. and with David almost all of the lead vocals are one take.”

A late addition to the team was keyboard virtuoso Rick Wakeman, who had played Mellotron on Space Oddity and was now drafted in to dress up Bowie’s piano parts. “he told me to make as many notes as I wanted,” Wakeman once said. “The songs were unbelievable – Changes, Life On Mars?, one after another. he said he wanted to come at the album from a different angle, that he wanted them to be based around the piano. So he told me to play them as I would a piano piece, and that he’d then adapt everything else around that.”

If Wakeman was a featured performer so too was the 100-year old Beckstein piano he played. Scott: “It was the same piano used on Hey Jude, the early Elton John albums, Nilsson, Genesis and Supertramp, among many others. That was one of Trident’s claims to fame – the piano sound. It was an amazing instrument.”

Nowhere was that piano better featured than on the kitchen-sink ballad Life on Mars? The song has often compared to Sinatra’s My Way (the album liner notes even say: “Inspired by Frankie”), and for good reason. In 1968 Bowie was asked by a publisher to submit English lyrics to a popular French chanson, Comme D’Habitude. his version, titled Even A Fool Learns To Love, was rejected in favour of another by former teen idol Paul Anka.

Bowie: “There was a sense of revenge in that, because I was so angry that Paul Anka had done My Way. I thought I’d do my own version. There are clutches of melody in that [Life On Mars?] that were definite parodies.”

A week before the sessions began, on May 30, Duncan Haywood ‘Zowie’ Jones was born, cracking his mother’s pelvis in the delivery. Bowie greeted his boy with Kooks, a charming ditty meant as both a paternal tribute and a warning. In the 1971 press release for Hunky Dory, he explained: “The baby looked like me and it looked like Angie and the song came out like, ‘If you’re gonna stay with us you’re gonna grow up bananas.’”

Actually, Zowie (now known as Duncan Jonesand an acclaimed film director) turned out fine, despite a mostly absentee father and being raised by a revolving cast of nannies and grandparents. Bowie confesses: “I might have written a song for my son, but I certainly wasn’t there that much for him. I was ambitious, I wanted to be a real kind of presence. and I had Joe very early. and with that state of affairs, had I known, it would’ve all happened a bit later. Fortunately everything with us is tremendous. But I would give my eye teeth to have that time back again, to have shared it with him as a child.”

Drawing on the “collision of musical styles” idea, Hunky Dory ricochets playfully through its 11 songs. From the lounge-meets-boogaloo gear shifts of Changes and the glam-ragtime stride of Oh, You Pretty Things, through the Tony newley-does- the-blues of Eight Line Poem to psyche-Dylan swirl of The Bewlay Brothers, it’s a thrilling hybrid.

“It was like, ‘Wow, this is no longer rock’n’roll. This is an art form. This is something really exciting!’” says Bowie. “I think we were all very aware of George Steiner and the idea of pluralism, and this thing called post-modernism which had just cropped up in the early 70s. We kind of thought, cool, that’s where we want to be at. Fuck rock’n’roll! It’s not about rock’n’roll any more, it’s about how do you distance yourself from the thing that you’re within? We got off on that. I think certain things had been done that were not dissimilar, but I don’t think with the sensibility that I had.”

That sensibility was abetted by the album’s secret weapon: guitarist and creative foil Mick Ronson. “What I’m good at is putting riffs to things, and hook-lines, making things up so songs sound more memorable,” the guitarist (who died in 1993) once said. and the proof abounds: his spare, searing licks on Eight Line Poem; the explosive acoustic on Andy Warhol; the nasally distorted power blast on Queen Bitch. all electrifying moments.

“I would put him up there with the best I’ve ever worked with,” said Ken Scott. “I think Ronno was better than any of The Beatles as a guitarist. his playing was much more from a feel point or melodic point of view.”

Woodmansey: “Mick didn’t really know how good he was. he would do a solo, first take, never played it before, and it would blow us away. David would always get Ken to push the record button without Mick knowing. he would do another six solos, but it was always the first or second one that we kept.”

Ronson’s gifts extended beyond his guitar playing. In the months prior to the sessions, he had been studying music theory and arranging with a teacher back in Hull. That bit of knowledge, combined with his innate musicality, made for the stunning string arrangements on songs like Life On Mars? and Quicksand.

“Ronno was great the way he’d go down to just one or two violins, then have the others come slowly but surely,” says Scott. “he didn’t quite know what he was supposed to do, so he was much freer. Much like The Beatles. he would do things other arrangers would never do.”

Angie Bowie says of the communication between her ex-husband and Ronson: “They were two Yorkshireman chatting away. Very full of respect for each other. They were young and very sweet, well-mannered, trying to be as professional as they could. I know that sounds boring, but it’s the truth. There were no drugs. They were just doing this wonderful album and everyone was thrilled at having a chance to participate instead of having to work horrible jobs.”

Side Two of the album featured a trio of “hero songs” inspired by Bowie’s visit to America. Queen Bitch was an exhilarating nod to the Velvet underground (Lou reed later said he “dug it”). Bowie says he had been fixated on the Velvets since the first time he heard their single Waiting For The Man. “It was like, ‘This the future of music! This is the new Beatles!’ I was in awe. For me it was a whole new ball game. It was serious and dangerous and I loved it”.

If Hunky Dory was David Bowie’s first masterpiece, it definitely wasn’t his last! It is an album that gave him a wider audience and seemed to open his horizons. Bowie recalled how people came up to him after the album came out and provided compliments (the first real time that has happened to him). If you do not own Hunky Dory on vinyl, then now is a perfect time to get it. In their review, this is what AllMusic observed:

“After the freakish hard rock of The Man Who Sold the World, David Bowie returned to singer/songwriter territory on Hunky Dory. Not only did the album boast more folky songs ("Song for Bob Dylan," "The Bewlay Brothers"), but he again flirted with Anthony Newley-esque dancehall music ("Kooks," "Fill Your Heart"), seemingly leaving heavy metal behind. As a result, Hunky Dory is a kaleidoscopic array of pop styles, tied together only by Bowie's sense of vision: a sweeping, cinematic mélange of high and low art, ambiguous sexuality, kitsch, and class. Mick Ronson's guitar is pushed to the back, leaving Rick Wakeman's cabaret piano to dominate the sound of the album. The subdued support accentuates the depth of Bowie's material, whether it's the revamped Tin Pan Alley of "Changes," the Neil Young homage "Quicksand," the soaring "Life on Mars?," the rolling, vaguely homosexual anthem "Oh! You Pretty Things," or the dark acoustic rocker "Andy Warhol." On the surface, such a wide range of styles and sounds would make an album incoherent, but Bowie's improved songwriting and determined sense of style instead made Hunky Dory a touchstone for reinterpreting pop's traditions into fresh, postmodern pop music”.

Fifty years after its release, Hunky Dory is still being played and studied. Such a wonderful album with huge hits such as Changes sitting alongside deep cuts like Fill Your Heart. It is a truly visionary and remarkable work from a legend we all miss very much. Produced by Ken Scott and David Bowie and released on 17th December, 1971, David Bowie’s Hunky Dory is…

AN unquestionable masterpiece.