FEATURE:

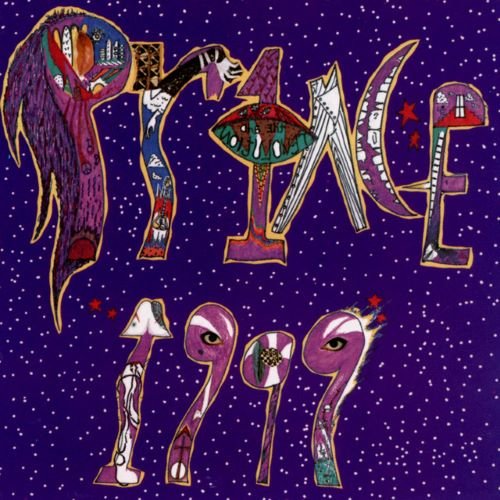

I Was Dreamin' When I Wrote This…

Prince’s 1999 at Forty

__________

THE master Prince…

PHOTO CREDIT: Ron Wolfson/WireImage, via Getty Images

released many genius albums in his life. Among his many masterpieces is 1999. Released on 27th October, 1982, his fifth studio was his best to that point. In fact, when you look at ranking lists like this, this, this and this, 1999 usually comes in at the number three position. Considering Prince released thirty-nine studio albums before his death in 2016, that is a pretty impressive feat! A staggering double album in a year when Prince was on a roll and releasing some of his very best music, I wanted to celebrate this incredible album ahead of its fortieth anniversary. I would encourage any music fan to buy the Deluxe edition of 1999 (you can see it being unboxed here). The New York Times wrote about it in 2019. Alongside the title track are classics like Little Red Corvette and International Lover. With songs lasting between four and nearly ten minutes, 1999 is an album that lets the material stretch, expand, and do its work. A gorgeously produced and realised album, 1999 still offers gifts and surprises forty years after its release! Seen as Prince’s breakthrough album, he followed up on the promise of 1981’s Controversy and began this purple patch. He would follow 1999 with perhaps the ultimate Prince album: the mighty and planet-conquering Purple Rain. The soundtrack to the film of the same name, how many artists have released two albums of that quality side by side?! It was a sensationally productive and golden period for the icon! 1999 was certified quadruple platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).

I am going to come to a couple of reviews for 1999. I often bring in features around big anniversaries. This is no exception. 1999 has been written about quite a bit, but there are a few features I want to highlight. PopMatters looked at the expanded Deluxe version of the album and provides some background about a time in Prince’s career where he was beginning to step into a league of his own:

“The most remarkable thing about the new, five-disc reissue of Prince’s 1999 is it makes the original record feel small. As released in 1982, 1999 goes deeper and reaches further than most pop albums, its tracks crawling past the seven-minute mark into the most frightening abysses. But as any Prince fan knows, 1999 is only the tip of the iceberg. All his albums come with acres of apocrypha, and the hours of unreleased material available here are even more daunting for being accessible at the flip of a record or the press of a button. We kind of have to listen to it now.

Prince was on a roll in 1982. It was a year of epics such as “Automatic”, great pop songs like “Raspberry Beret”, and soulful abstractions like “How Come U Don’t Call Me Anymore?” Had he hung up his ruffled shirt after the inspired but awkward Controversy from the year before, he might’ve been remembered as a studio weirdo like Shuggie Otis or Todd Rundgren, an icon to boomers and DIY hermits but few others. Following an unprecedented spurt of creativity that should be on any shortlist of the best years ever enjoyed by a musician, it was clear there was no mentioning him in the same breath as anyone. He’d put in enough hours by the time he was 23 to produce a masterpiece with almost unconscious ease.

During the fallow years between the early 1970s heyday of black art-pop and the desegregation of MTV, it was hard to be noticed as a young, black auteur. Prince responded by encouraging false rumors about his race and cultivating a guitar-god mythos to appeal to the rock kids on the other side of the radio dial who might’ve still been mad about disco. Boos on tour with the Rolling Stones made clear that wouldn’t happen for a while, but to this day, rock fans are less likely to cite his music than his prowess on that most phallic of instruments as the reason for their admiration.

1999 is the sound of Prince deciding not to give a shit. The guitar is not central to 1999; its most heroic solo, on “Little Red Corvette”, was played by Dez Dickerson of the newly formed Revolution. Prince still wrote pop songs, but not in any conventional sense of the word, and the strongest tie to rock is in its use of strenuous song lengths to impart a sense of awe rather than just to keep the party going at the club. 1999 is one of the most uncompromising records ever made by a star who could be considered ascendant. It’s telling that so many of its modern progeny – Beyonce’s self-titled, Rihanna’s Anti – are made by artists with an established-enough brand that people would buy their most avant stuff on name recognition alone.

The opening stretch of the album might turn off anyone whose impression of Prince is just another 1980s hitmaker. “1999” and “Little Red Corvette” are ubiquitous. The latter is so burned in our brains it’s easy to miss how brave it is, using as it does what could be a throwaway Big Sean line – “Girl you got an ass like I never seen / And the ride is so smooth you must be a limousine” – as the emotional climax of the whole song. “Delirious”, the culmination of Controversy‘s rockabilly flirtation, is made with such a light touch it might not immediately scan as great art, even as its rubbery construction plays tricks on our brain.

It’s in the latter three sides that Prince emerges as pop’s wickedest genius. The stretch from “Let’s Pretend We’re Married” through “All the Critics Love U In New York” represents some of the furthest out pop music has ever gone while remaining resolutely pop. Though the sheer size of the tracks is daunting, they move with a diseased grace, like an eel swimming up a polluted urban canal. Verse-chorus structures are irrelevant. Without ever sounding cluttered or overambitious, 1999 finds room for monologues, dialogues, codas, solos, sound-effects orgies, and long segments where an instrument will just build by itself.

What makes “Let’s Pretend We’re Married” sound like the marathon sex it describes isn’t its perfectly deployed F-bombs (the word sounds genuinely transgressive in Prince’s mouth), but its Linn LM-1 patter. The Linn is the instrument Prince masters on 1999 in lieu of guitar, and the legions of Chicago house producers who bought their own after its release found replicating Prince’s programming as daunting saving up the money for one. The beat builds unaccompanied for the song’s opening minute, its eighth-note obstinacy creating a tension that never lets up. With each passing second, we drift further away from the light into the record’s fetid bowels

Both “Let’s Pretend We’re Married” and nine-and-a-half-minute centerpiece “Automatic” deepen in the same fashion. Prince starts by singing about sex, not particularly lasciviously, and as the song progresses, we’re treated to a foley-studio interpretation of the act itself. On “Let’s Pretend We’re Married”, it’s the disappearance of the melody, the elimination of all distractions but the drive to orgasm followed the dirty talk Prince fearlessly spits into his paramour’s ear. On “Automatic”, it’s what could be a dentist’s drill, followed by moans of pleasure that—like the ones on “Lady Cab Driver” a few tracks later, as he dedicates his individual thrusts to the higher powers—sound more like moans of pain. The sounds Prince himself makes in the throes of lust are nearly as disturbing as James Brown’s, not least his screams.

Anyone whose interest in Prince has anything to do with his much-touted sexual fairness should reconsider, not least because two songs from the 1999 sessions, neither of which made it onto this disc (“Extraloveable,” “Lust U Always”), cast Prince as a rapist. Sex doesn’t sound much fun on most of 1999; it’s a means to an end more than anything else. The hero of “Let’s Pretend We’re Married” uses a fantasy of monogamy to justify his reckless promiscuity to himself. It’s implied that Prince fucks the heroine of “Lady Cab Driver” in lieu of paying the fare. Only on “International Lover”, which is basically self-parody, is anyone having any real fun.

1999 is really an album about staving off oblivion. The title track is about partying in the face of nuclear annihilation. There’s a whiff of apocalypse about 1999, and Prince, fresh out of the theater from Blade Runner, cleverly surrounds his characters with the signifiers of 1980s retro-futurism: computer bleeps, automated voices, synth pads like malignant rain, sampled traffic and crowd noise. Prince could sound cheeseball when he engaged with futuristic themes on any level deeper than an aesthetic veneer, which is why “Something in the Water”, for all its gutting, paranoid desperation, has aged least elegantly of these songs”.

Classic Pop looked at the making of 1999 earlier this year. I do wonder whether those who heard Controversy in 1981 and were listening to Prince in 1982 had any idea that he would unleash an album as remarkable as 1999! Purple Rain expanded further and solidified his genius. In a year as wonderful as 1982, 1999 might be the most recognisable and popular album of that time. It still sounds awe-inspiring in 2022! Let’s learn more about its history and impact:

“As far as we’re aware, Prince is the only pop star to have been honoured with his very own Pantone colour. ‘Love Symbol #2’ is its name and no prizes for guessing it’s a rather delicious shade of purple. But it’s not just a colour that Prince has claimed as his own.

He has come to define his own unique sound, to the point where the very word ‘Prince’ has itself become a musical shorthand for adding a little more spice into a performance: “Can you please make it sound a bit more Prince?” In other words, more funky, more visceral, more sexy… you know, more Prince.

A prodigious talent, Prince had long been shocking audiences, not only with an incredible musicianship, but also with song titles alone to make you blush. A gifted multi-instrumentalist and prolific songwriter, he had refined his sound and look across four studio albums in just four years between 1978 and 1981.

An incredible feat for any group, but even more so for a solo artist who did it all largely single-handedly, writing, performing and producing almost everything.

By the turn of the 1980s, Prince had gained a degree of notoriety on the R&B circuit, was playing sizeable venues to a select audience, and had gained himself some influential fans (Mick Jagger among them), but crossover success still eluded him. Album number five would correct that. If you had never heard of Prince before 1999, that all changed swiftly.

On 1999, Prince reached an artistic and commercial apex, finally becoming a mainstream artist five albums into his career. It was the moment that he had been building up to; the culmination of the work he’d put in to get to that point, refining the vision and building upon what had come before.

As well as his penchant for the colour purple and being friskier than a Duracell bunny on heat, Prince was particularly well known for his singular vision. His desire for total creative control is legendary.

He played every single note of every instrument on his first album, For You, and that solitary approach essentially set the template for his first few records. Gradually, however, he began to open up the door to let a select few individuals into his private world.

By 1999, a distinct change in approach was emerging. Perhaps by now he had proved the point, gained the self-assurance, or simply found the right people. Whatever the logic, he became increasingly more collaborative (or, at least, willing to delegate specific tasks to others under his meticulous direction).

While Prince still played the vast majority of the instruments on 1999, there were exceptions. Notably, he relinquished the Little Red Corvette guitar solo to his axeman, Dez Dickerson, (whereas on earlier albums, he surely would have opted to play it himself). Crucially, 1999 marked the introduction of his band, The Revolution.

It wasn’t a sudden outpouring of modesty, but all part of his masterplan. Dickerson has described Prince as both ‘spontaneous’ and ‘calculating’, “in a good way”, always with an eye on the commercial implications.

Giving his band a name on the bill – rather than being an anonymous bunch of session musicians – cemented their status as a unit, making the enterprise feel bigger and more substantial.

Prince’s willingness to share the stage is pointedly demonstrated in his decision to give the opening lines of the song 1999 (and hence the album) to his band mates. Far from diminishing his role, this move served only to strengthen it.

It’s the classic theatrical move of building the suspense and saving the best until last. In holding back his own dramatic entrance, it made it all the more potent when the moment arrived.

But this development extended beyond just his immediate band. Prince was building a family – perhaps even an army – with himself as the patriarch. Better to be the leader of a gang than go it alone, a mere sole trader. What’s more, the notoriously prolific songwriter was in such top form that he was churning out more songs than he could deal with.

His vision was too large for just one individual to carry. Why bother fighting to join a scene when you can simply make your own?

So that’s exactly what Prince did, creating other vehicles for expression, nurturing projects including groups The Time and Vanity 6. He even adopted the producer alter ego, Jamie Starr, a moniker that allowed him to explore another side of his character that he couldn’t under his own name.

These activities weren’t ancillary; they were all part of his bigger vision. But, of course, he planted himself as the centrepiece, and the Minneapolis movement’s totem statement was his landmark album, 1999.

Prior to recording 1999, Prince got burnt opening for The Rolling Stones – his outrageous attire and sexually provocative demeanor proved too much even for this audience and they were heckled and booed off stage amidst a barrage of missiles.

Prince’s response was to decamp to the studio, immerse himself in music and, according to Minneapolis music journalist Andrea Swensson, become “a superstar on his own terms.” Rather than going to the audience, make the audience come to you.

With 1999, Prince pioneered his own signature sound with its own definable characteristics, a sexy, synth-laden funk-pop, with elements of rock and R&B combined to create something totally fresh.

The futuristic sound was enhanced with synth stabs typically replacing a live horn section, and heavy use of the recently released Linn LM-1 Drum Computer, which Prince would feed through his guitar pedals to create even more otherworldly sounds.

This technology allowed the family unit to become more self-sufficient than ever. With a whole range of new sounds to tap into at their fingertips, the possibilities were endless. This distinct style became to be known as the Minneapolis sound. First expounded by Prince and his wider family, it was replicated by others outside the fold around the world.

Indeed, a certain would-be King of Pop took direct influence from the punchy synths of 1999 on his own burgeoning masterpiece.

It’s interesting to observe that while both Prince and Michael Jackson set out – dripping in confidence – to make defining records that would cement their superstar status, there is one very notable difference in their approaches. Unlike Thriller, which is consciously streamlined and trimmed down to its core essence, 1999 is the polar opposite of lean.

Where MJ gets straight down to the point, Prince allows each track the space to gestate, bubbling up slowly, like a physical workout routine that builds and builds before eventual climax.

Had Quincy Jones produced 1999, he would undoubtedly have shaved a sizeable chunk off the running time – after all, he thought the intro on Billie Jean was too much. But in Prince’s hands, 1999 is essentially one long victory lap. It feels as if he’s performing extended versions of well-established hits live, rather than introducing them for the first time on record. Four tracks extend over seven minutes, with Automatic rolling on for nearly ten.

It’s certainly an indulgence, and though it might be deeply sacrilegious to say so, the album could easily have been distilled down to under an hour.

Still, you just have to admire Prince’s unshaking bravado and refusal to truncate his vision. Prince was thinking visually, cinematically, even. An avid fan of movie nights with his inner circle, he took much inspiration from the big screen.

Quadrophenia apparently inspired the trench coats and (in turn) his own music movie, Purple Rain. By 1999 Prince had shaped a futuristic look befitting the music – shimmering hair, boxy jackets and guitars as angular and razor-sharp as the tunes. The birth of MTV in 1981 proved the perfect outlet for Prince to present the entire package to whole new audiences.

At the turn of the 80s, American radio was still notably segregated. Yet 1999’s singles went on to enjoy heavy rotation on mainstream radio and MTV. As such, the album was notable for making Prince one of the first black artists to get such broad airplay on the wider pop channels, as opposed to the R&B charts alone.

Prince now appealed to the white record-buying public, and in doing so, opened the door for others in his wake.

1999 was the album that propelled Prince into the big league. It gained him his first Grammy nomination and first Top 10 album. But he achieved this without diluting his vision; he didn’t suddenly become more acceptable to conservative sensibilities. After all, there are some very naughty bits on 1999 – he was as controversial as he had ever been.

Yet he refined his pop hybrid sound and brought in rock elements that enabled him to open doors previously closed to him. 1999 also set up the juggernaut that followed, 1984’s Purple Rain. Prince was in his stride and had entered a genuine purple patch that’s still pretty mind-boggling 40 years on”.

I am going to end with a couple of reviews for the monumental 1999. In its apocalyptic title track, Prince proclaimed that (in 1982) he was going to party like it was 1999. One of his most indelible and addictive choruses, 1999 is one of eleven masterful songs on a double album that ranks alongside the best of all time. This is what Pitchfork observed in their review:

“For all the hot-pink light bathing 30-years-on memories of the '80s, that decade was full of dread—bad guys lurked around corners, and the threat of nuclear war hovered over the world’s geopolitik. 1999, Prince’s fifth album, opens with reassurance: “Don’t worry, I won’t hurt U,” a mushily robotic voice announces. “I only want U to have some fun.” The song that follows is the record’s title track, and with its lyrical laser focus on the world possibly ending, if not imminently then eventually, it fulfills that promise. Prince realizes the power of saying “Fuck it, let’s party” in the face of near-assured annihilation, a gesture that foments an effervescent, uncontrollable glee. (Which, here, is depicted by mashed-on keyboards and a joyously wailed policy of ejecting anyone who might be in a less-than-celebratory mood.)

But we all die eventually, right? That’s the attitude that runs through much of 1999, which powers itself with machines like the Oberheim OB-SX and the Linn LM–1 while taking a slightly more sober view of the pleasures that dominated so much of Prince’s earlier work. Dangers—the bomb, “brand new laws,” sneering critics—get their airing, and time might be running out (Party over, oops!). Best, then, to get in all the good stuff while one still can, whether those feelings come from extended make-out sessions in the back of a slick car (the simmering “Little Red Corvette,” which emerges from a plume of smoke to become one of Prince’s most potent fusions of funk’s swing and rock’s swagger), late-night secrets about love and lust told among icy synthscapes (the stretched-out seduction “Automatic”), or Prince’s Holy Quadrality of Dance, Music, Sex, and Romance (the jittery “D.M.S.R.”).

1999 is a sprawling double album (“D.M.S.R.” was cut from initial CD pressings to make it fit on a single disc) on which Prince indulged his curiosity in new technology, but what’s remarkable about it is how tightly-wound it feels, even on the more far-flung jams. “Something in the Water (Does Not Compute)” is claustrophobic and tense, Prince’s pleas to a lover who’s left him behind made even more frantic by the cacophony of digital sounds ricocheting around the mix. (It’s the song that probably brings Prince’s admitted influence of Blade Runner to mind the most.) “Lady Cab Driver” unfolds like a movie playing on fast-forward in Prince’s dirty mind, with a request for a “ride” turning into a bit of slap-and-tickle play before fading back to reality—as evidenced by scritching guitars and the reprise of the song’s feather-light hook.

Then there’s “Delirious,” one of Prince’s most unbridled offerings, its wheezing keyboards sounding like a mind left alone to whirl, propelled by a dizzyingly upbeat drum track and Prince’s half-sneeze vocals. The one-two punch of that track and the Erotic City staycation “Let’s Pretend We’re Married” is enough to drive even the most buttoned-up listener to their own personal brink—one that arrives even before Prince murmurs, “I’m not sayin’ this just 2 be nasty/I sincerely wanna fuck the taste out of your mouth/Can U relate?” Well. When U put it like that…

It’s not all fun and sex games, of course; even though “1999” makes the idea of impending apocalypse alluring, the planet still goes kablooey when all is said and done. The piano ballad “Free” presents Prince in tender mode, smearing the personal and political together as he sings “Be glad that u r free/Free 2 change your mind.” The music grows increasingly stirring, with militaristic drums and fiercely slapped bass fighting for supremacy as Prince sings of creeping clamp-downs. And “All the Critics Love U in New York” takes the self-regard exhibited by the city and its more pretentious inhabitants and mashes it into a ball. But those forays into the wider world only give the more pleasure-minded tracks on 1999 more urgency and lightness.

Prince played with different toys on 1999—new synths, new sexual frontiers, new paranoias. He bent them to his will, though, and this 11-song opus was the result. Balancing synth-funk explorations that would reverberate through radio playlists’ ensuing years, taut pop construction, genre-bending, and the proto-nuclear fallout of lust, 1999 still sounds like a landmark release in 2016; Prince’s singular vision and willingness to indulge his curiosities just enough created an apocalypse-anticipating album that, perhaps paradoxically, was built to last for decades and even centuries to come”.

I am going to finish up with a review from AllMusic. I have not heard of a new fortieth anniversary edition of 1999. I know that there will be new features and investigations of a sensational album:

“With Dirty Mind, Prince had established a wild fusion of funk, rock, new wave, and soul that signaled he was an original, maverick talent, but it failed to win him a large audience. After delivering the sound-alike album, Controversy, Prince revamped his sound and delivered the double album 1999. Where his earlier albums had been a fusion of organic and electronic sounds, 1999 was constructed almost entirely on synthesizers by Prince himself. Naturally, the effect was slightly more mechanical and robotic than his previous work and strongly recalled the electro-funk experiments of several underground funk and hip-hop artists at the time. Prince had also constructed an album dominated by computer funk, but he didn't simply rely on the extended instrumental grooves to carry the album -- he didn't have to when his songwriting was improving by leaps and bounds. The first side of the record contained all of the hit singles, and, unsurprisingly, they were the ones that contained the least amount of electronics. "1999" parties to the apocalypse with a P-Funk groove much tighter than anything George Clinton ever did, "Little Red Corvette" is pure pop, and "Delirious" takes rockabilly riffs into the computer age. After that opening salvo, all the rules go out the window -- "Let's Pretend We're Married" is a salacious extended lust letter, "Free" is an elegiac anthem, "All the Critics Love U in New York" is a vicious attack at hipsters, and "Lady Cab Driver," with its notorious bridge, is the culmination of all of his sexual fantasies. Sure, Prince stretches out a bit too much over the course of 1999, but the result is a stunning display of raw talent, not wallowing indulgence”.

On 27th October, 1999 is forty. Kicking off with the insatiable title track and ending with International Lover, it is an odyssey and voyage into the mind and soul of the much-missed Prince. Few albums open with a more potent one-two-three as 1999, Little Red Corvette and Delirious. You get gripped and hooked by the first notes and stay until the end. We are living in quite an apocalyptic and strange times so, strangely, there is a relevance to an album released in 1982. Prince is here to often salvation, inspiration and music that helps you...

FORGET your troubles.