FEATURE:

Paradise City

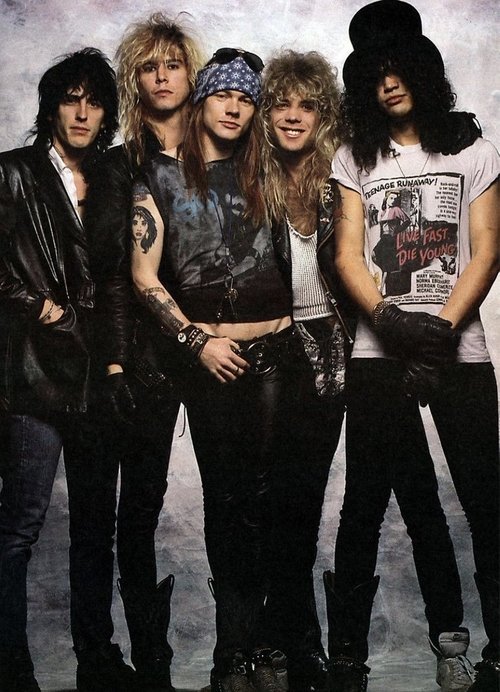

Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite for Destruction at Thirty-Five

__________

A monster of an album…

that topped charts, sold huge numbers and is considered one of the best ever, the initial reviews for Guns N’ Roses’ debut, Appetite for Destruction, were not all glowing. A sort of Hair Metal, Rock and Glam mixture from a band led by Axl Rose must have been an unexpected and hard-to-appreciate-at-the-time combination in 1987! Released on 21st July that year, I wanted to spotlight an album that is celebrating a big anniversary soon. Featuring iconic songs like Welcome to the Jungle, Paradise City, and Sweet Child o' Mine, I think that most Guns N’ Roses fans would put Appetite for Destruction at the top of their list. It is a wonderful album that has gone through reappraisal. At the time, some objected to Appetite for Destruction. Whether they felt Guns N’ Roses were a combination of other bands or were a bit cliched, it did take a while for the album to get this huge acclaim. Now seen as a watershed moment and one of the very best albums ever, Appetite for Destruction has won many more positive critical reviews since its initial batch in 1987. In a spectacular year for music – classics from Prince, Michael Jackson, Eric B. & Rakim, INXS, and U2 among them -, Guns N’ Roses debut was quite unlike anything else. I think that one reason why Appetite for Destruction remains so intriguing, durable, and popular is the fact it does not sound dated. Thanks to the varied songwrtiting from the band and excellent production from Mike Clink, here is an album that will be discovered, played and treasured for decades to come.

Like I do with album anniversary features, I am going to end with a couple of reviews of Appetite for Destruction. It is interesting reading all of the reviews for the album, as everybody has their own take on a truly awesome album. Before getting to that, Loudwire wrote about the story of Appetite of Destruction in July 2021. I have highlighted a few parts that are particularly illuminating and helpful:

“In an era of bad-boy rockers who weren’t terribly bad and wrote music that sounded too good, Guns N’ Roses were the genuine article. Their songs echoed with the love for rock and roll and the spirit of rebellion. When Geffen Records A&R man Tom Zutaut signed the band he had no idea what he had gotten into. No one else wanted GN’R because they were viewed as a liability, a band as likely to miss the show as perform a gangbuster set. Yet what Zutaut heard from vocalist Axl Rose, guitarists Slash and Izzy Stradlin, bassist Duff McKagan and drummer Steven Adler was inspiring and seemed to have the potential to be a profitable signing if they didn’t all die in an alcohol or drug related mishap.

“There are some bands that just can’t be stopped and you can sense it,” Zutaut says. “No amount of alcohol or drugs will slow them down. Guns N’ Roses were able to consume those things, yet, deliver at a live show and deliver in the studio. I don’t know if that makes them like gorilla glass on a cell phone or what, but there are plenty of bands that probably did less heroin than Guns N’ Roses and drank less alcohol, but imploded. For every Guns N’ Roses or Motley Crue that delivers, there’s probably 10 bands that are great but fall apart before they even become successful.”

Impressed by Guns N’ Roses’ ability to endure under adverse conditions, Zutaut paid producer Spencer Proffer $15,000 to record “Nightrain” and “Sweet Child of Mine,” as a test and if the chemistry was good he would stay on for the debut. He also agreed to record a few extra songs with the band for the EP Live Like a Suicide, which Geffen released in England under a different label to pique interest in the band before they toured there.

“Proffer didn’t produce those songs, his engineer just recorded them,” Canter says. “GN’R recorded those songs in two or three weeks at a time when they were totally out of control. Even Axl wasn’t in the best shape, and he was the cleanest out of all of them. But he was fooling around with whatever they were doing. Once he saw that they were totally spun out, he just stopped. But nobody showed up on time. They’d throw up or pass out in the studio. But they got the songs done. They recorded nine songs in that studio including 'Heartbreak Hotel,' 'Don’t Cry' and 'Welcome to the Jungle.' But they only used those four. And then they used 'Shadow of Your Love' as a b-side.”

The writing sessions for Appetite for Destruction were brief and frantic, largely because they band was aching to get into the studio again and record their first album, but also because they wrote many of the songs on their debut before the band got signed. McKagan had “It’s So Easy,” Stradlin presented “Think About You,” “Anything Goes" was a Hollywood Rose tune and Slash, McKagan and Adler had started “Rocket Queen” when they were in the band Road Crew. “Mr. Brownstone,” a warning of sorts about the allure of heroin, came quickly to Slash and Stradlin, largely because they wrote from experience.

“Slash once told me, ‘You know, you do heroin once and it’s such a high, that you want to do it again,” says the band’s former European publicist Arlett Vereecke. “The problem with that is, the minute you do it a second time, you’re addicted to it. Axl wasn’t really doing drugs because of the medication he was on. He was not a big drinker either. People have a misconception about that, but he was the clean and mostly sober one, really. He wanted to preserve his voice, and he was serious about it”.

I can imagine being a teen in the mid/late-1980s and getting these phenomenal albums out. It must have been exciting learning about a band like Gun N’ Roses arriving with Appetite for Destruction. It is such a confident album; it is impossible to not be affected by it. Even if it was knocked by some in 1987, critics have come around. Even if there is this sense of the lurid and overly-macho on many songs, Appetite for Destruction is more sophisticated and nuanced than it being a low and knuckle-headed album. This is what Pitchfork observed in their review back in 2017 (when the album turned thirty):

“From their grimy photo shoots that became Metal Edge pinups to their candid discussions of how they survived before hitting it big (“Strippers were our main source of income. They’d pay for booze, sometimes you could eat...” Slash told Rolling Stone), Guns N’ Roses were often portrayed as a clouded mass of debauchery with insatiable needs to simultaneously consume and destroy. “We are just being ourselves, but at the same time, these ’bad boy’ images tend to sell,” Axl told SPIN in 1988. Slash told Melody Maker something similar that same year: “We’re not mean, we’re not nasty, we’re decent people. We’re just out for a good time, like five teenagers on the loose.”

The Parents Music Resource Center panic that took hold in the mid-’80s helped fuel GNR’s reputation as “bad boys.” The band were open about their vices on record and in interviews, but their wide-ranging appeal, despite the cluck-clucking of reactionary critics, wasn’t merely the result of them wearing their indulgences on their sleeves. They had shrewd ears and wide-ranging influences, resulting in a sound that used bouncing-ball grooves with punk’s economy that vibrated with paranoia and antipathy yet could (very occasionally) settle into romantic bliss. Bassist Duff McKagan came from the Seattle punk scene, drumming for the legendary hyper-power-poppers Fastbacks; he and drummer Steven Adler would hone their rhythm-section camaraderie by listening to Cameo and Prince LPs. Slash, the London-born son of a costumer who designed for Bowie, decided to pick up the guitar when he heard Aerosmith’s 1975 opus Rocks, telling Guitar World that the album’s “drunken, chemically induced powerhouse sound just sold me and changed me forever.” Izzy Stradlin, the band’s chief songwriter who’d escaped Indiana with Axl, had a Charlie Watts air about him, being the coolest guy in the room while he laid down riffs from which Slash’s solos could take flight.

“Welcome to the Jungle,” the album’s opener, is followed by “It’s So Easy”—one of the greatest one-two punches in rock history. A snarling chronicle of the void at the center of any Dionysian orgy, it’s powered by Adler’s butterfly-bee drumming and riffs that sound like they’ve been turned into pistons. The lessons in funk taken by Adler and McKagan make the album’s most harrowing moments roll out of the speakers all throughout—the shimmying that underlies the rancid takedown of a cleaned-up bad girl on “My Michelle,” the musical portrayal of the “West Coast struttin’” by the blotto protagonist of “Nightrain.” Axl’s scorched-earth upper register is at key times doubled not just by his bandmates, but by a low-pitched version of his own voice—detailing that adds another edge to the group’s dystopian reveries.

Even with Appetite’s thick layers of grime, its path to mainstream success was shoved along by songs that reflected a bit of Southern California sunshine. “Sweet Child O’Mine” was the album’s big hit, a mushy love song set aloft by Slash’s thick arpeggiating (which, as he told Rolling Stone, was a “goofy personal exercise” overheard by Axl, who decided to write lyrics to it ) and Axl’s doe-eyed lyrics. It’s not all light-hearted—his initially muttered, eventually yelped, “Where do we go? Where do we go now?” that peppers the bridge reveals his ever-present search for more as the song resolves in a minor key.

The album’s most triumphant moment is the Jock-Jam-in-waiting “Paradise City,” a fever-dream anthem where green grass and lovely women abound, where everyone’s so cheerful that no one will give you shit if you add a synthesizer to the mix. The main riff is one of those so-simple-it’s-criminal melodies that get arenas shaking; when it double-times at the song’s end, with Slash freaking out on a solo and Axl pleading to be taken haaaawwoooooommmmeeee, it’s an invitation to exhume the toxins of the mean streets and the meaner drugs and the even meaner people and to just thrash away their residue”.

Another review I want to highlight is from Louder Sound. Packed with so many great songs and a band (Axl Rose, Slash, Izzy Stradlin, Duff ‘Rose’ McKagan and Steven Adler) so connected and electrifying, I think Appetite for Destruction is an album that will continue to find fans, influence bands, and remain high in the polls of the greatest albums of all-time:

“But at the heart of the album was a core of truly great songs: In many ways, Welcome To The Jungle is the definitive Guns N’ Roses song, and an album opener which – from Axl’s opening words, ‘Oh my God’ – warns the listener in no uncertain terms that they better buckle up tight for the road ahead. Detailing Indiana boy Rose’s first wide-eyed, open-mouthed impressions of Los Angeles, this was the first song Slash and Axl ever wrote together, and it remains the ultimate statement of Guns’ fearless, reckless, last-gang-in-town swagger.

It’s So Easy was Guns’ first UK single, a snarling, seething introduction which double-dared you to get closer to these obnoxious, aggressive, misogynist shitbags. It’s hardly the band’s most sophisticated tune, but no other early Guns song carries such bad-boy menace.

And if much of Appetite declares that Los Angeles is a dirty, depraved, dangerous shithole, Paradise City is the album’s kicker – an admission that Guns N’ Roses wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. The quintet’s first UK Top 10 single, its simplistic singalong melody is arguably a little too eager to please, though the song may have had less global appeal had the band not changed its original lyric: ‘Take me down to the paradise city, where the girls are fat and they got big titties’. Slash’s guitar playing, meanwhile, transforms the whole thing into a sleaze-rock Born To Run, all marauding riffs and elegiac solos.

Mr. Brownstone, You’re Crazy, Out Ta Get Me: the album oozes bad attitude and is littered with great lines (‘I used to do a little, but a little wouldn’t do, so the little got more and more’, ‘Some people got a chip on their shoulder/An’ some would say it was me’, ‘Welcome to the jungle it gets worse here everyday/You learn to live like an animal in the jungle where we play’). And in Sweet Child O’ Mine, Guns N’ Roses had a secret weapon: a beautiful rock ballad inspired by Southern rock icons Lynyrd Skynyrd. Slash didn’t much care for the song at first, dismissing it as “sappy” and his own lead guitar melody as “this stupid little riff”. But it topped the US chart for two weeks in September 1988, regularly tops polls to find the greatest guitar solo or riff, and it remains the best-loved song of Guns N’ Roses’ career.

Appetite For Destruction arrived at the height of the hair metal era and was born of the LA rock scene, but its roots lay in the great rock music of the 70s – in Aerosmith, Led Zeppelin, AC/DC and the Sex Pistols. It’s the newest album in the top 10 and understandably so – has anybody made a better rock’n’roll record since its release?”.

On 21st July, Appetite for Destruction turns thirty-five. I was only four when it came out, so I am not sure how people reacted. I know that, through the years, it has been afforded so much praise. It is a mighty album that has (in my view) never been bettered by the band. One of the greatest debut albums, Appetite for Destruction came fully-formed and fierce from…

THE amazing Guns N’ Roses.