FEATURE:

All Is Full of Love

Björk's Stunning Homogenic at Twenty-Five

__________

IT is hard to think…

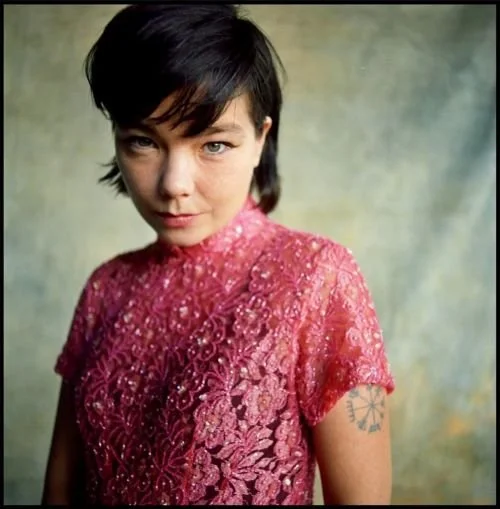

IN THIS PHOTO: Björk in 1997/PHOTO CREDIT: Danny Clinch

of any artist who has had such a successful run of albums than Björk. Five years after her ninth studio album, Utopia, she has announced that Fossora is her next release. It will come out in the autumn. The icon has also unveiled a podcast where she explores her discography. Björk only releases albums with one-word titles. I like that. It is focused and more defined than a lot of other artists – ones that have lengthy titles. I am really looking forward to her tenth studio album. She has barely dropped a step or put a foot wrong since her 1993 debut, Debut. The quality has been sky-high for the past few decades! One of most acclaimed and astonishing is her third studio album, Homogenic. It was released on 22nd September, 1997. That year was one of the most remarkable years for music. Bands like Radiohead were entering new territory and breaking ground. Heavy-hitting and hugely atmospheric releases from the likes of The Prodigy, The Chemical Brothers, and Spiritualized defined the year. It was such an exciting and interesting year where things had moved on and evolved since the mid-1990s. Similarly, Björk’s music was shifting and changing. Keeping some of the Trip-Hop sounds of her previous two albums, Homogenic focused more on similar-sounding music combining electronic beats and string instruments, with songs in tribute to her native country Iceland. Recording began in London. She had to relocate after surviving a murder attempt by a stalker. Relocating to Spain, it was a tense period for Björk. That is not really reflected in Homogenic. By all accounts, the actually recording and production was smooth and productive. Working with Mark Bell, Guy Sigsworth, Howie B and Markus Dravs, Homogenic is a masterpiece. I am going to come to a couple of the many positive reviews for the album.

On 22nd September, 1997, Björk released one of the most spectacular albums of the decade. There are a couple of articles that I want to bring in now, so that we can get an idea of the making of Homogenic and the period leading up to the album. First, in 2017, SPIN revisited their 1997 cover story with Björk when marking twenty years of a truly astonishing album. It is shocking reading some of the turmoil and turbulence Björk was caught up in before recording Homogenic:

“1996 was Björk’s year in the barrel. While on tour in Asia, Björk arrived in an airport in Bangkok and was descended upon by a bunch of television reports. The most aggressive telejournalist of the bunch shoved a microphone into her ten-year-old son’s face and tried to interview him on live television, saying to him at one point, “It must be really difficult to have a mom like that.” Björk—who says she has only lost her temper two other times in her life—snapped, beat the stuffing out of the reporter, and then, in an unintentional display of her recently acquired karate skills, threw her to the ground. The footage immediately went into heavy rotation on the Hard Copys of the world, and turned Björk into a most unexpected tabloid subject. Several months later, a crazed fan in Miami, disturbed by Björk’s impending mixed-race nuptials to jungle star Goldie, sent her a letter bomb and then killed himself. (The letter bomb was intercepted by police; she and Goldie never tied the knot.) Overnight, photographers were camped outside her London home, and Björk went from being the cultish and irresistible iconoclast of dance music—a hipster novelty from a strange land—to an international celebrity. The fuss has mostly died down, but it was, she says, the most “outrageous, mental year of my life.” With some distance on these events, she now believes she was asking for it. “I sent out messages,” she says, “and I got answers: Please put me on the edge of a cliff and will someone please kick me off.”

Björk’s response to her emotional crash was to fly off to El Madroñal, a small town on the southern coast of Spain, where she spent several weeks sleeping, Jet Skiing, and making music. If we are inclined, as Björk seems to be, to find the silver lining, then her beautiful, spooky, difficult new album, Homogenic, appears to be it. It is a minimalist masterpiece. The extravagant disco show tunes of yore are gone, and what’s left are the fuzzier musical experiments that popped up on Debut and Post, her first two solo records after leaving the punkish Icelandic band the Sugarcubes in 1992. A head-on collision of often contrary sounds—the Icelandic String Octet; the electronic, ahead-of-the-curve weirdness of coproducer Mark Bell of techno outfit LFO; and Björk’s outsized, unprecedented voice—Homogenic, she says proudly, is her least compromised work to date. “It’s the record that’s closest to the music that I hear in my head. It’s closest to what I am.” But. “I don’t know if people are going to like it or not.”

Neither does her record label. “Björk’s challenging her audience, and, more so, radio, to get beyond traditional song structure, to step outside their comfort zone,” says Greg Thompson, senior vice president at Elektra. “So yeah, it’s a challenge. No doubt. I liken her to Beck. They’re not necessarily radio-driven, single-driven artists. They conceive great albums. Björk’s concept is to combine strings and hip-hop beats, and quite frankly, from radio’s standpoint, that’s difficult to mix in with Sugar Ray.”

While Björk has charted 11 Top 20 singles in England, she has yet to have the same commercial impact in America (Homogenic debuted at No. 28 on the Billboard Top 200.) The worldwide combined sales of Debut, Post, and Telegram (last year’s remix album) total around six million, with her biggest single success in America coming from “Army of Me,” a song from Post that appeared on the Tank Girl soundtrack. Despite the steady momentum gained from the MTV airplay of 1993’s “Human Behavior” (Björk being chased by a bear) and ’95’s “It’s Oh So Quiet” (Björk dancing with a mailbox) and electronica’s recent Stateside foot-in-the-door, chances are remote the the bizarro Homogenic will launch Björk beyond her cute, cuddly cult. The album’s first single, “Joga,” a love letter to her best friend, feels nearly a cappella, a barely detectable beat humming under Björk’s soaring vocals. The stuttering, scratchy “5 Years” sounds as if it was recorded in a video arcade circa 1980. “Immature” repeats the same four lines over and over (“How extremely lazy of me!”) over a church bell-laced beat. You get the idea. Unless your name is RZA, such avant-garde strivings don’t do much for your bankbook. When Thompson says that the folks at alternative radio are “waiting for her to make that one gem that actually works as a radio song,” you can be sure that he knows it’s not on Homogenic.

Though Björk’s loath to put down Americans and our notorious need to categorize pop music into endless charts and radio formats, she can’t help herself. “It’s American radio’s own worst enemy,” she says. “Music, to me, stands for freedom, and to be so limited is the opposite of what music is.” And even within our endless sub-categories, it seems to her, we’ve still gotten it all wrong. “I went to New York last January and did some interviews and they were all like, ‘Electronica is the next big thing,’ and I’m like, ‘Please.’ And they put it under the same thing as Prodigy, Kraftwerk, Massive Attack—the whole lot. To them it’s this thing that was born half a year ago. Please.”

To Björk, the charge that techno is inherently cold and soulless—the typically rockist, typically American criticism formerly known as “disco sucks”—is patently absurd. There is no soul in a guitar, she points out; someone has to play it soulfully. “I saw this magazine called Guitar,” she says, with a smirk, “and there was this comic in the back with this blues guy with a guitar, and the question was, ‘Why will computers never take over the guitar?’ And the final thing was, ‘Well, you can never call a computer Layla.’ Please! Have you heard the names all the kids give their computers?! They’re like pets. Please!”

“Settled in, at last, for band rehearsal, Mark Bell and engineer Allan Pollard are on stage fiddling with the pets: a 909 drum machine, a brand new, powerful effects unit called a Sherman—that is no bigger than a typewriter—a keyboard, and a mixer. They are gearing up for an eight-city mini-tour of nightclubs around Europe hat kicks off in Munich a couple of days from now. All of the shows are low-key affairs—either barely promoted or unannounced—that will allow Björk and Bell some time to learn to play off each other before the Icelandic String Octet is brought in for the tour proper that begins in November. This is, in many ways, a new model for onstage musical performance: one person pushing buttons—remixing live, really—the other singing. “I think I can say this has never been done before,” Björk announces. Many of the songs will be left “open” so that Bell “can drop things in and surprise me. And then it’s just eye contact. It’s all very free-form.”

Bell has remixed parts of Homogenic for this tour, better to suit a late-night disco experience. He plays for Björk his pumped-up drum track for “Alarm Call”—it’s both deafening and skittish, a nimble feat—at which point Björk joins Bell onstage and begins to dance from one end to the other, sometimes skipping, sometimes marching, sometimes standing in place and twisting her torso in a strange reverie. She’s wearing an odd pants-with-a-skirt combo, a faded black T-shirt, and funny little canvas shoes that, she will tell me later, are worn by Japanese men who build houses. They make her feet appear webbed. The performance—Björk’s mad dance, her improbably voice, the unlikely outfit, the schizophrenic beats—reminds me of nothing so much as Alice in Wonderland, a trippy little universe unto itself. When Björk sings the line “I’m no fucking Buddhist / But this is enlightenment,” the track sputters out, and she and Bell matter-of-factly huddle, swapping asides on this tape loop and that string noise. Bell heads back to work. Björk comes down off the stage, yawns, and says, “I need meat.”

A few blocks away from the rehearsal studio, Björk sits in front of a huge plate of crispy duck, devours it like a hungry truck driver, washes it down with red wine, and explains to me why she’s titled such a weirdly eclectic new album Homogenic. “This album is only songs that were written last year,” she says, while Post and Debut were like back catalogs of all the songs she’d always wanted to record—of all her obsessions with different sounds and ideas from different times in her life. Those records weren’t as much solo projects, she says, as collections of duets with the producers who had inspired her: Nellee Hooper, 808 State’s Graham Massey, Tricky, Howie B. “This is more like one flavor. Me in one state of mind. One period of obsessions. That’s why I called it Homogenic.”

Those obsessions were, improbably, pre-Off the Wall Michael Jackson (“I love Michael Jackson so much. He’s got a ridiculous, outrageous, stubborn faith that magic still is with us.”) and 20th-century string quartets. “I went to music school in Iceland for ten years,” she says, “and obviously I was introduced to a lot of music.” In some ways, Homogenic is a return to her classical training, “going back through everything I learned,” she says, “and trying to focus on where I was in that moment.” With the help of Asmundur Jansson, a musicologist friend in Iceland who has been making her tapes since she was 14, Björk would sit down to compiled cassettes of, say, songs about ships or songs featuring angular, out-of-tune brass. “I went to him h`oping to find a treasure,” she says. “I really wanted to discover what Icelandic music is, and if there is such a thing. And in a way, there really isn’t.”

It is not a very big leap from this discovery, or lack thereof, to conclude that perhaps Björk herself is Icelandic music. Iceland is a country obsessed with literature and story-telling (think Viking sagas), to the exclusion of nearly all other arts. And, unlike America and Europe, countries that industrialized slowly over a period of a few hundred years, Iceland has come into the technological present fairly recently. Björk’s grandfather, for example, lived in a mud house. Out of this sped-up modernization sprang both an almost mythological relationship to nature and a brand-new fixation on technology. “All the modern things / Like cars and such,” Björk sings on Post, “Have always existed / They’ve just been waiting in a mountain / For the right moment… / To come out / And multiply / And take over.” And on Homogenic‘s “Alarm Call”: “I want to go on a mountain top / With a radio and good batteries”.

I know that is a lot to grab from SPIN, but it is such an amazing and detailed feature/interview. I want to move on to Classic Albums Sundays. Their feature about the making of Homogenic is excellent. Every fan has their own favourite Björk album. In terms of the critical reaction and the kudos Homogenic has received through the years, this one is right near the top:

“With this album, Björk dug even deeper into London’s underground electronic scene, the sounds of which she absorbed, processed, and transformed into her most experimental work up to this point. She initially intended to produce the album herself and started writing with Brian Eno co-producer Marcus Dravs in her own home studio. She later opted to recruit other producers and brought back Howie B with whom she had collaborated on “I Miss You” for Post. And she was finally able to snag pioneering producer Mark Bell of LFO, who along with Eno and Stockhausen, was a big inspiration and would remain a collaborator through to her 2007 album Volta. Other production credits went to Seal and Bomb-the-Bass co-writer Guy Sigsworth along with Björk, herself.

The sounds on the album were a marriage between her love of strings once again orchestrated arranged by Deodato and this time performed by the Icelandic String Octet, and her infatuation with abstract electronic beats and sonics which she felt were just as pure. She told Jam! Magazine, “Most people look at technology that it’s cold and people that use synthesizers and all these samples are lazy bastards who just have everything on tape and just press ON and out comes the song, which of course, isn’t true. Synthesizers are quite an organic, natural thing.”

The name Homogenic also suggests the concept of home. While recording she revealed to Jam!, “I’m really seeking after something that’s Icelandic. And I want it to be more me, this album. Debut and Post are a bit like the Tin Tin books. Sort of Tin Tin goes to Congo. Tin Tin goes to Tibet. So it’s all these different flavors, me sort of trying all these different things on, which is very exciting, but now I think it’s a bit more Björk goes home.” On the song “Unravel”, one of the album’s highlights and a favourite of Tom Yorke, she used a traditional Icelandic choir singing technique which was a combination of speaking and singing”.

I am not sure whether there is a twenty-fifth anniversary release of Homogenic. If you want to know more about the album, then I would recommend this book from Emily Mackay. Although not every reviewer was positive towards Homogenic in 1997, most of the reaction was incredibly positive. In retrospect, that has only increased. The album has been reassessed in terms of what came next and how the music scene changed. One band who were influenced by Homogenic were Radiohead. Their guitarist Ed O'Brien claimed Björk inspired them to change their musical style for their fourth studio album, Kid A (2000). This is what AllMusic wrote in their review for the emotionally deep and spectacularly beautiful Homogenic:

“By the late '90s, Björk's playful, unique world view and singular voice became as confining as they were defining. With its surprising starkness and darkness, 1997's Homogenic shatters her "Icelandic pixie" image. Possibly inspired by her failed relationship with drum'n'bass kingpin Goldie, Björk sheds her more precious aspects, displaying more emotional depth than even her best previous work indicated. Her collaborators -- LFO's Mark Bell, Mark "Spike" Stent, and Post contributor Howie B -- help make this album not only her emotionally bravest work, but her most sonically adventurous as well. A seamless fusion of chilly strings (courtesy of the Icelandic String Octet), stuttering, abstract beats, and unique touches like accordion and glass harmonica, Homogenic alternates between dark, uncompromising songs such as the icy opener, "Hunter," and more soothing fare like the gently percolating "All Neon Like." The noisy, four-on-the-floor catharsis of "Pluto" and the raw vocals and abstract beats of "5 Years" and "Immature" reveal surprising amounts of anger, pain, and strength in the face of heartache. "I dare you to take me on," Björk challenges her lover in "5 Years," and wonders on "Immature," "How could I be so immature/To think he would replace/The missing elements in me?" "Bachelorette," a sweeping, brooding cousin to Post's "Isobel," is possibly Homogenic's saddest, most beautiful moment, giving filmic grandeur to a stormy relationship. Björk lets a little hope shine through on "Jòga," a moving song dedicated to her homeland and her best friend, and the reassuring finale, "All Is Full of Love." "Alarm Call”'s uplifting dance-pop seems out of place with the rest of the album, but as its title implies, Homogenic is her most holistic work. While it might not represent every side of Björk's music, Homogenic displays some of her most impressive heights”.

I am going to finish off a part of Pitchfork’s review of Homogenic. They gave it a perfect ten in 2017. I don’t think Homogenic will ever lose any of its influence and incredible power. It is an album that you need to hear in its entirety and surrender yourself to:

“Björk’s voice is, without question, the life force of this music. You can hear her finding a new confidence on “Unravel”: The edge of her voice is as jagged as the lid of a tin can, her held tones as slick as black ice. A diligent student could try to transcribe her vocals the way jazz obsessives used to notate Charlie Parker’s solos, and you’d still come up short; the physical heft and malleability of her voice outstrips language.

Videos had long been an important part of Björk’s work, but they became especially crucial in building out the world of Homogenic. Compared to the sprawling list of collaborators on her first two records, she had pared down to a skeleton crew for this album; working with an array of different directors, though, allowed her to amplify her creative vision.

Chris Cunningham used “All Is Full of Love” as the springboard for a tender, and erotic, look at robot love. Michel Gondry turned “Bachelorette” into a meta-narrative about Björk’s own conflicted relationship with fame—an epic saga turned into a set of Russian nesting dolls. Another Gondry video, for “Jóga,” used CGI to force apart tectonic plates and reveal the earth’s glowing mantle below. At the end of the video, Björk stands on a rock promontory, prying open a hole in her chest—a pre-echo of the vulvic opening she will wear on the cover of Vulnicura—to reveal the Icelandic landscape dwelling inside her. In Paul White’s video for “Hunter,” a shaven-headed Björk sprouts strange, digital appendages, eventually turning into an armored polar bear, as she flutters her lids and wildly contorts her expression—a vision of human emotion as liquid mercury. Her use of different versions of her songs for several of these videos also contributed to the idea that the work was larger than any one recording—that these songs were boundless.

Björk’s initial idea for Homogenic was to be an unusual experiment in stereo panning. She imagined using just strings and beats and voice—strings in the left channel, beats in the right channel, and the voice in the middle.

It’s kind of a genius idea: an interactive, self-remixable album, a sort of one-disc Zaireeka, that goes to the heart of the dichotomies that have always made Björk—theorist and dreamer, daughter of a hippie activist and a union electrician—such a dynamic character. And while it’s easy to see why the concept never came to fruition—there’s no way such a gimmick could have yielded an album as richly layered as Homogenic turned out to be—it turns out to have been a prescient idea: the direct antecedent to Vulnicura Strings, which excised the drums and electronic elements of Vulnicura and focused on voice and strings alone”.

I know there will be a lot of new inspection of Homogenic closer to its twenty-fifth anniversary in 1997. Following the acclaimed and remarkable Debut and Post (1995), few could have precited just where the always-unpredictable and innovative Björk would head next. She would release her fifth studio album, Vespertine, in 2001. It was yet another stunning album from an artist, as I say, who has not released anything other than wonderful and unique. 1997’s Homogenic is a monumental and utterly spellbinding album from…

ONE of music’s greatest geniuses.