FEATURE:

Go Deep

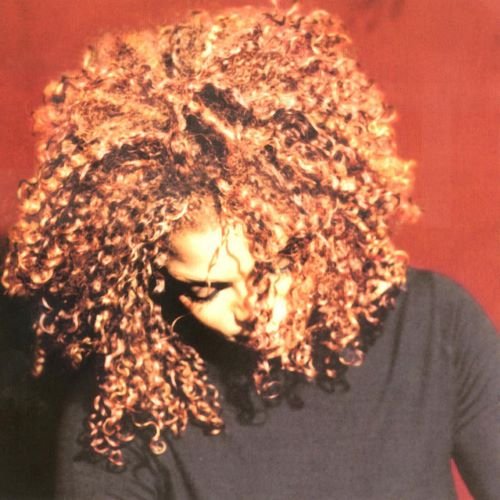

Inside Janet Jackson’s The Velvet Rope at Twenty-Five

__________

PERHAPS the most mature…

and ambitious album of her career to this point, Janet Jackson’s The Velvet Rope came out on 7th October, 1997. I have seen a lot of great reviews for it, though some have given it a more mixed reception. There were high hopes before the release. 1993’s janet. is a phenomenal album. Prior to the release of The Velvet Rope, Jackson renegotiated her contract with Virgin for U.S.$80 million, the largest recording contract in history at that time. Between the release of her 1993 album and The Velvet Rope, Jackson experienced emotional breakdown and stress. The Velvet Rope is a more introspective and harder-hitting album than its predecessor. Jackson discussed her personal struggles throughout, in addition to domestic abuse, sexuality, same-sex relationships and social issues. It is a very important and deep album that has never quite received all the acclaim it deserves. Many highlighted the racier elements of The Velvet Rope, rather than the range and nuance of the music, the more serious themes Jackson addresses, plus how honest and open she is throughout. I think there has been fairer retrospection. Considered to be one of Jackson’s darker, most personal, and intimate albums, The Velvet Rope has influenced artists like Rihanna and Kelly Rowland. It is an incredible album coming up to its twenty-fifth anniversary. Reaching number one in the U.S. and spawning incredible and successful singles like Together Again, there is no doubting the fact The Velvet Rope is iconic and hugely important.

Because of that, I want to mix some reviews for the album with features that go deep and explore its making and legacy. The first, from Udiscovermusic.com, is from earlier this year. They highlight the timeless intimacy of the phenomenal The Velvet Rope:

“Janet Jackson’s longevity and versatility as an artist is largely credited to her ability to shapeshift between albums, exuding power one moment and vulnerability the next. She was already iconic, having several successful albums under her belt and a reputation for passion and precision on stage. Each of Janet’s previous albums was layered with radio hits and seemed to carve out a specific narrative: superstar. In the midst of battling a deep depression, Janet chose to get more raw and confessional with her art. On The Velvet Rope, Janet experimented with displaying heartache, loneliness, and sensuality for all to see – forcing us to delve deeper into wondering who she was as a person, and as an artist.

While Janet is indirect about specifics pertaining to the album, one theme is clear: pain. When pressed for more details explaining the lyrics for “What About,” she told Rolling Stone. “Singing these songs has meant digging up pain that I buried a long time ago. It’s been hard and sometimes confusing. But I’ve had to do it. I’ve been burying pain my whole life. It’s like kicking dirt under the carpet. At some point, there’s so much dirt you start to choke. Well, I’ve been choking. My therapy came in writing these songs. Then I had to find the courage to sing them or else suffer the consequences – a permanent case of the blues.”

Vulnerability in art is nothing new, but Janet contorts through her pain like a trapeze artist; swinging over the crowd and performing for us, catching herself and swinging to keep from plummeting, both eyes fixed on the rope in front of her. She used The Velvet Rope as divergence from her previous understandings and measurements of success, noting that she previously stifled her feelings and just performed for the sake of success rather than out of passion or a deep yearning to do so. By the time Janet made Velvet Rope, she’d opened up feelings of past trauma to explore herself as a woman and artist. She got tattoos and piercings – physical markings of emotional pain.

Despite the overwhelming theme of pain with a tinge of emotional anguish, Janet insists that the symbol of the rope is not meant to be one of harshness but one of mystery. “The music is sensual, not brutal. The feeling of The Velvet Rope is soft, not severe,” she told Rolling Stone. After living through celebrity from childhood, with her life fully on display for consumption, Janet said she never was asked if she wanted to be a performer. But she performed. After leaving her feelings of distress and isolation unaddressed through adolescence and early adulthood, Janet chose to wield the inner torment of fame and its underlying stressors as a weapon against hiding. This album isn’t just about sex. It’s about growth into adulthood and the pain that comes along with being alive.

Although Janet’s elaborate conceptual theme was constantly questioned by critics, listeners seemed to understand. Velvet Rope went multi-platinum and was Janet’s fourth album to chart on the Billboard 200. The album has sold over 10 million copies worldwide, being certified triple Platinum in Canada, double Platinum in Australia, and Platinum in Japan, Europe and France. The album navigates topics of bisexuality, queer positivity, and S&M, cementing Janet as a gay icon. She was awarded the ‘Outstanding Music’ award by GLAAD Media – Janet has since been honored with a Vanguard award by GLAAD.

The Velvet Rope influence isn’t strictly relegated to musical artists. Activist Janet Mock named herself after Janet Jackson, and cites the sexual fluidity and sexual autonomy on Velvet Rope for being an album that paralleled her own life at the time. Psychologist Alan Downs’ book Velvet Rage illustrates growing up gay in a world that largely caters to heterosexuals. Artists across genres and platforms have cited the influence and significance of this album in their own work, attempting to mold their own pain and self-discovery into a risky, autobiographical element. Janet’s impact is still being heard in other artists’ work, decades later, cementing her status as an icon and permanently defining the parameters – or lack thereof – needed for a raw, intimate, mature pop album”.

I like the idea of The Velvet Rope’s title referring to this sense of emotions being kept behind a rope or at bay. Maybe a sense of happiness or strength slightly out of bounds. Although The Velvet Rope is very personal, it is accessible and has a lot of joy throughout. In 2017, Albumism celebrated twenty years of a supreme and rich album that continues to inspire artists today:

“Importantly, there was a new ingredient at play here: neo-soul. This R&B sub-genre was to bring artistic relief to a black music scene soon to become rife with super producers and manufactured talent as the 1980s closed. Starting in 1991 with Omar, the sub-genre grew each subsequent year with efforts from Caron Wheeler, Meshell Ndegeocello, D’Angelo and Maxwell. This movement influenced the imaginations of black artists far and wide. Jackson is no exception, as neo-soul carried the Blaxploitation/freestyle merger of “Free Xone” and the bare-faced piano preciousness of “Every Time.” Neo-soul also touched Jackson’s visual aesthetic for The Velvet Rope. Two of its partnering music videos directed by Mark Romanek (“Got ‘Til It’s Gone”) and Seb Janiak (“Together Again”) were celluloid encomiums to Afrocentrism.

But while The Velvet Rope brought Jackson back to her rhythm and blues homebase, the LP did not engage in total R&B isolationism. She tied in bits and pieces of alternative rock and electronic influences too, as heard on the squally title track and “Empty.”

Quite the musical meal when served up on October 7, 1997, The Velvet Rope asked for patience while unmasking its treasures. The set’s singles―“Got ‘Til It’s Gone” (featuring Q-Tip), “Together Again,” “I Get Lonely,” “Go Deep,” “You,” and “Every Time”―were fantastic lures for what awaited listeners on The Velvet Rope en masse.

Jackson’s sixth LP marked a new pinnacle for her, both critically and creatively. Since then, only Damita Jo (2004) has been able to enter The Velvet Rope’s orbit as her secondary masterpiece. By granting temporary access to the “spiritual garden” of Janet Jackson on The Velvet Rope, audiences can experience and celebrate the complexities of this woman, great and small”.

I shall round off with a couple of reviews. The first, from Random J Pop is really glowing and positive. It made me think about Janet Jackson’s award-winning sixth studio album in a new light. There is no doubting the fact The Velvet Rope is such an important and stunning album:

“There didn't seem to be any rules when it came to putting this thing together. Janet and her partners in crime, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, really pull from the edges for The Velvet Rope to make songs whatever they want them to be. The album casually swings from Electro Pop, to Rock, to Funk, to R&B, to Dance music, to Pop, and then back again. Sometimes with fusions. Sometimes with a different twist. No two songs on this album sound the same, and half of it is unlike anything Janet had done before. An album like this could easily be alienating. But the anchor is the familiarity of Janet's voice, and the feelings she conveys through these songs.

Whilst Rhythm Nation tried its damnest to make commentaries on capitalism, violence and social constructs, it was easy for these songs to get lost in how bouncy they were (i.e "State of the World") or the sequencing. An absolute banger of a song about feeling good and free-spirited coming after a song which touches on children having to grow up into a broken world kinda robs the focus. The Velvet Rope has a far better flow to it. Everything about the album feels more fluid and presents a narrative which flows from song to song. Starting with feeling lost ("The Velvet Rope"), to experiencing loss ("Together Again"), to loneliness ("Empty" and "I Get Lonely"), to being open to being loved ("Anything"), to then finding your place in the world ("Special").

The theme of The Velvet Rope is loss and a lack of belonging. But there's still some joy to be found in the songs, even if it doesn't shout it from the rooftops. The "Tubular Bells" sampling "Velvet Rope" is about those who hurt others being truly seen. Acknowledging that sometimes people who hurt others do so because of their own hurt. And that whilst many wouldn't give them the time of day, showing enough compassion to allow them to love others and love themselves is how we all win. "Together Again" was written following Janet losing a friend to AIDS. But the song is not about the anguish at the loss. It's about that person's everlasting memory, and the notion of there being an existence where Janet will get to see them again. "Together Again" is known for its Dance, House influenced sound, but it was originally written as a ballad, and it's not hard to hear it. "Free Xone" is a 5 minute spoken-word funky get-down, with a message which is basically 'People be gay' before it became a meme featuring Quinta Brunson. "Go Deep" is about being so tired of life that you're like 'Fuck it, I'mma go out, drink, maybe fuck around a little'.

But not every song has a silver lining, as is true to life. "Got 'til It's Gone" is what it says on the tin. Realising what you've lost, that you'll never get it back, and continually being tormented by the wonder of what could have been. "Empty" is about being your truest self online, and connecting with somebody who understands you in ways that nobody in your offline life does, and raising the question of how 'real' a relationship is that you've built with somebody online. "Empty" has aged like the finest of wines given where the world is now in an age of social media, dating / hook-up apps and online gaming. It honestly makes more sense to me now than it did when I first heard it way back.

The Velvet Rope's charm is in how relatable its songs are. Some songs may not even click with you at first, and you'll only appreciate them because of the production. But then, you really listen to what Janet is saying, and then you find yourself like 'Oh, shit. That's me!' And it's not to shame or make anybody feel bad. It's simply to make you feel. The acknowledgment that you aren't as alone as you may have thought you were. And that as vast as this universe is, there will always be at least one other person out there who gets it and gets you for who you truly are. You may not ever meet that person, but they are out there. This is what The Velvet Rope represents. Belonging and the championing of acceptance.

Pop owes an everlasting debt to Janet Jackson. Janet's impact on music seemed to have been wiped off the table all because her left titty guest featured in her Super Bowl performance, but there's no escaping that pop would not be what it is without Janet Jackson. But I also feel that the impact that The Velvet Rope specifically had on Pop music gets overlooked. We may not have had Janelle Monáe's Dirty Computer, Rihanna's Loud, Beyoncé's Lemonade or Kelela's Take Me Apart (which even share similar visual colour palettes) if it wasn't for this album. Janet not only made it okay for women in Pop to lay their feelings and insecurities bare in a song, but she normalised Black women in Pop being able to do what was largely only done within Soul, Blues and R&B - as though these are the only genres in which Black woman can extricate their pain.

The Velvet Rope wasn't just an affirmation of belonging for people who felt they were different. It was for Black girls who wanted to be boundless Pop stars. That reinvention, drastic image changes, controversy, and living your best Pop star life weren't exclusive to Madonna. That you ain't gotta be white to be able to do any of this shit. Black girls can do all of these things too, because Janet was doing it too”.

The final review that I am going to include is from SLANT. Although they note that there is a lot of sexual openness and frankness, something more compelling and emotive lies beneath the surface of a terrific album:

“If Janet Jackson made much ado of janet. being the Let’s Get It On to Rhythm Nation’s What’s Going On, then 1997’s The Velvet Rope is clearly her I Want You, respectively Jackson’s and Gaye’s best and least-heralded albums. (Both incidentally recognized at the end of their creators’ respective marriages.) The chief difference between The Velvet Rope, the least “perfect” album of Janet’s increasingly careful career and the one that most threatens to collapse at each turn, and all the albums that Janet has released since is that all the subsequent albums have been cheery, forcedly carefree collections of would-be singles without any cohesiveness behind them; they’re kiddie cocktails by someone old enough to know better. The reason none of them sound particularly convincing—like Jane Adams’s Joy from Happiness gamely grinning “I’m doing good” seconds before peeling into miserable, anti-cathartic tears—is because of The Velvet Rope, an album by a still very inexperienced person attempting to convey maturity and worldliness.

In every conceivable way the most “adult” album of Janet’s career, The Velvet Rope is also the most naïve. Its vitality owes almost nothing to its stabs at sexual frankness. Because, truthfully, a lot of the “naughty” material doesn’t exactly seem that much more convincing than the Prozac-fuelled aphorisms of the follow-ups, nor is it more politically intriguing than her advocacy of color-blindness in Rhythm Nation.

The bisexuality of her cover of Rod Stewart’s “Tonight’s the Night” never manages to convince that Miss Jackson has ever been so nasty as to even consider loosening pretty French gowns. “Rope Burn” isn’t so ribald that Janet doesn’t have to remind listeners that they’re supposed to take off her clothes first, though producers Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis’s Chinese water torture beat does approximate sonic bondage. It’s hardly surprising that when Janet uses the word “fuck” in “What About,” she’s not talking about it happening to her. For a sex album that also seems to aim at giving fans an unparalleled glance behind the fetish mask (literally, in the concert tour performance of “You”), Janet’s probably never been more cagey.

But behind the sex is something even more compelling, because it gradually dawns on you that Janet’s use of sexuality is an evasive tactic. That it’s easier for her to sing about cybersex (on the galvanizing drum n’ bass “Empty,” one of Jam and Lewis’s very finest moments, maybe even their last excepting Jordan Knight’s “Give It to You”) and to fret about her coochie falling apart than it is to admit that it’s her psyche and soul that are in greater danger of fracturing. Soul sister to Madonna’s Erotica (which, in turn, was her most daring performance), The Velvet Rope is a richly dark masterwork that illustrates that, amid the whips and chains, there is nothing sexier than emotional nakedness”.

On 7th October, The Velvet Rope celebrates twenty-five years. It would be four years until Janet Jackson followed this masterpiece with All for You. A less consistent album in my view, I was eager to explore and highlight the brilliance of The Velvet Rope. It is an album that everyone should know and listen to – so, if you have not done so for a while then make sure that you do. The Velvet Rope was confirmation (as if it was needed) that Janet Jackson is a hugely important, influential and…

LEGENDARY artist.