FEATURE:

We Have to Let It Linger

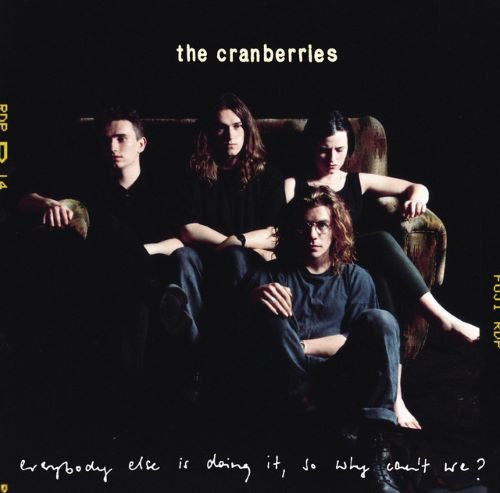

The Cranberries’ Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can't We? at Thirty

_________

ON 1st March, 1993…

the Irish group, The Cranberries, released their stunning debut album, Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can't We? One of the best debuts of the 1990s, it was written entirely by the band's lead singer Dolores O'Riordan and guitarist Noel Hogan. The much-missed O’Riordan is the band and album’s strongest point I think. Her voice makes every song sound so essential and moving. Upon its release, Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can't We? reached one in the U.K. and Ireland. Amazingly, The album spent a total of eighty-six weeks on the U.K. chart! A twenty-fifth anniversary edition of the album came out in 2018. Even though we lost O’Riordan in January 2018, her incredible talent and influence still resounds and resonates. The Cranberries’ debut album is her at her absolute best. Co-writing the songs with guitarist Noel Hogan, Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can't We?, what a talent O’Riordan was! I want to get to a few reviews for the simply divine and timeless debut from The Cranberries. In Pitchfork’s review from 2021, they give us some introduction as to how Dolores O'Riordan joined the band. It is so compelling that it makes me wonder whether we should get a biopic about The Cranberries so that we can see this story come to life!

“O’Riordan grew up about 10 miles outside Limerick in the rural townland of Ballybricken. The youngest of seven children, and one of two girls, O’Riordan learned early on that her voice would set herself apart: She was the precocious student that was asked to sing in Gaelic in front of the class, the tiny niece uncles brought around local pubs to entertain sloshed patrons. On her first day of secondary school, O’Riordan declared that she was going to be a rockstar before launching into a Patsy Cline song. She would go on to sing with a school choir that would frequently sweep the boards at Slogadh, an Irish youth arts festival. A devout Catholic, O’Riordan would later credit the church where she played the organ as the place that helped her envision music as a potential career. In 1992, she contextualized her band’s success as a kind of religious karma: “I could be just superstitious, but I think what’s happening now is a kind of a reward.”

After the audition, as O’Riordan headed out the door, the band handed her a tape with a loose sketch of a song—maybe she could think of some lyrics? The track consisted of four simple chords but, as O’Riordan remarked a few years later, “I took them home and I just wrote about me.” One week later she returned with a song that would change the foursome’s lives. Inspired by O’Riordan’s first kiss and the swift sting of rejection, “Linger” condenses every stage of heartache into four-and-a-half minutes of pop perfection with a few humble tools: an acoustic guitar riff, O’Riordan’s wistful humming, Lawler’s rolling drumbeat, and swooning orchestrals that aim for visions of grandeur far beyond the cheap synthesizer that produced them. The problem, as O’Riordan tells it, is that she gave her heart to someone, they stomped on it, and now she’s left holding the pieces. “But I’m in so deep/You know I’m such a fool for you/You got me wrapped around your finger,” she sings, her Irish brogue warming the edges of every syllable. All she wants is a little compassion moving forward: “Do you have to let it linger?”

As if galvanized by their new member, the band quickly began writing and performing with a newfound intensity. As O’Riordan later recounted, she initially assumed that people would find the cards-on-the-table emotion of songs like “Linger” too “girlie girlie.” “The music was so emotional I found that I could only write about personal things….I was sure that it would be considered soppy teenage crap, especially in Limerick, because most bands are really young (men), and their lyrics are humorous or mad. They don’t go pouring their hearts out,” she said. But the appreciation of O’Riordan’s vulnerability proved a point: everybody’s got a heart that breaks.

Once relegated to brief mentions in the local newspaper, by the summer of 1991, the band—now blessedly called the Cranberries—were British indie media darlings, especially after they signed a reported six-figure deal with Island. The press was especially charmed with O’Riordan, who was initially as unguarded in interviews as she was in song. Despite her shy nature and tendency to sometimes perform with her back to the audience, O’Riordan became the band’s mouthpiece, offering soundbites about her unfamiliarity with basic music equipment and passionate endorsement of the Catholic church.

That fall, Melody Maker visited the O’Riordan home in the Ballybricken and spotlighted the family’s soon-to-be-slaughtered Christmas turkeys, a kitschy Jesus clock, and supposed “gallons and gallons of Lourdes holy water.” “The Cranberries in general, and Dolores in particular, bring new meaning to words like innocence and naivete,” an Irish magazine quipped. (“Just because every second word isn’t ‘fuck’ and every song isn’t about sexual intercourse, people think it’s innocent,” O’Riordan retorted in 1992.) O’Riordan’s songwriting was vulnerable and her origins were certainly humble. But more often than not, these details played into sexist attitudes that align emotional awareness with fragility rather than a certain strength.

In March of 1993, after extensive soul-searching and some behind-the-scenes managerial drama, the Cranberries released their debut, Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We? If the band’s initial ascent to fame had exploited O’Riordan’s sensitivity as an oddity, Everybody Else bears no evidence that her heart was hardened as a result. “Linger” reappears and ascends to “Be My Baby”-levels of yearning thanks to the grandiose handiwork of producer Stephen Street, who had worked with the band’s beloved Smiths on albums like Meat Is Murder and The Queen Is Dead. “Dreams,” which articulates how falling in love is thrilling and terrifying all at once, achieves similar heights. From the first words out of O’Riordan’s mouth—“Oh my life/Is changing every day/In every possible way”—“Dreams” embraces the uncertain adventure ahead. With every new line, the band seems to breathe in fresh new air, constantly revitalizing themselves in real-time; at one point, O’Riordan lets out a defiant yodel, a vocal tradition that she was taught by her father.

Everybody Else is an album about relationships and the ways that a pair of people can love and hurt each other with equal intensity. Unfortunately, O’Riordan is consistently the one whose heart is getting broken. (“I was always one for the tears,” she once said.) Across 12 songs, the wind that once swept O’Riordan up into a gust of romantic euphoria has disappeared, leaving her desperate to understand where she—or her lover—faltered and everything fell apart. “Sunday” examines the dissolution from both sides, beginning with the other person’s unhurried romantic indecision, which is conveyed atop a gentle string arrangement. As if to express how destabilizing this waffling makes her feel, when it’s O’Riordan’s turn to vocalize her own perspective, the song shifts into a tighter, more upbeat melody. “You’re spinning me around/My feet are off the ground/I don’t know where I stand/Do you have to hold my hand?,” she tells her aloof lover. “You mystify me.”

While only “Dreams,” “Linger,” and “Sunday” channel swirling bliss, every song on Everybody Else blazes a path towards catharsis. Sometimes the exact conflict O’Riordan is trying to process can be difficult to pinpoint—“Still can’t recognize the way I feel,” she sings at one point—but this is an album that sinks into the idea that simply feeling can be enough. When O’Riordan is conflicted about a breakup, as on opener “I Still Do,” the band kicks up a grungy squall around her. Meanwhile, the seething betrayal of “How” boils over into a flood of rage, urged on by a blistering guitar riff, which Noel Hogan delivers as if he were trying to outrun the fire set by O’Riordan’s anguish. The Cranberries sound ridiculously tight as a unit, but their most expressive asset is always O’Riordan’s voice. In the band’s early days, she was often compared to Sinéad O’Connor; a feeble observation rooted in the fact that they were both Irish. But on the Cranberries’ heavier songs, O’Riordan moved into a class of her own: Every syllable becomes a tussle in miniature, either ripped from her mouth in protest, spat out in disgust, or bursting forth in delicious victory. On “Not Sorry,” you can hear her lips curl around each word: “Cause you lied, lied/And I cried/Yes, I cried, yes I cry, I cry, I try again,” she bellows, channeling the Gregorian chants that captivated her as a child”.

I can’t find too many features about how the album was made. There is this interview from 1993 that is worth checking out. I would advise people buy Everybody Else Is Doing It So Why Can't We? on vinyl if they can. It is a breattaking album that still sounds as fantastic all these years later. It turns thirty on 1st March. On its twenty-fifth anniversary, Albumism paid tribute to the remarkable work of The Cranberries. An album without any weak moments, Everybody Else Is Doing It So Why Can't We? Is a huge treat:

“Comprised of twelve meticulously crafted, compact songs with an average run time of 3:20, Everybody Else Is Doing It is wholly devoid of filler and packs a melodic, melancholic punch very much in the vein of The Smiths’ most beloved fare, albeit without their infamous frontman’s caustic swagger and sneer. And while the soaring, evocative soundscapes constructed by the Hogan brothers and Lawler warrant plenty of praise, it is unequivocally O’Riordan’s versatile vocals and introspective lyrics that command the most rapt attention.

Just 21 years old at the time of the album’s arrival, O’Riordan invites the listener on an autobiographical journey from adolescence to adulthood, the vicissitudes of young love providing the central thematic focus from beginning to end. "I know exactly what every song on that album was about," O'Riordan explained to Rolling Stone in 1995. "And I know exactly what night I wrote it on and why I wrote it. And I'm kind of proud of them because they do elaborate very much how I felt at that time."

Somewhat surprisingly considering the album’s critical and commercial success, first stateside and subsequently in the UK, only two official singles were released. But each of these songs is damn near flawless. Unveiled five months before the album launch, lead single “Dreams” is an uplifting love song that finds O’Riordan reveling in new love, her sweet—yet never saccharine—vocals gliding seamlessly atop the lush, propulsive arrangement.

Even more revelatory is “Linger,” the ode to fading love that catapulted The Cranberries’ profile when MTV latched on to the black and white, Jean-Luc Godard inspired video, with radio stations across the U.S. following suit shortly thereafter. Replete with sweeping, string-laden orchestration coupled with O’Riordan’s yearning, lilting vocals, it’s a perfect specimen of pop ballad grandeur, a timeless tune that remains just as fresh and inspired today as it was twenty-five years ago.

Non-single standouts abound across the expanse of the album, the theme of reconciling love and loss pervasive throughout all of them. The haunting album opener “I Still Do” finds O’Riordan grappling with her conflicted feelings toward her lover. The same disposition resurfaces later on “Sunday” and “Wanted,” each propelled by jangly guitar work reminiscent of The Smiths and The Sundays’ most transcendent moments.

The music and O’Riordan’s lyrics assume a noticeably more sullen tone on the brooding “Pretty,” in which she takes a condescending lover to task, and “I Will Always,” a lovelorn, lullaby-like lament about setting her partner free to explore his independence.

Not all is weighed down by doom and gloom, however, as the percussive “How” unfurls as a seething kiss-off to a wayward lover, while “Not Sorry” serves as an anthem of redemption, with an empowered O’Riordan reclaiming her sense of self in the wake of an abusive relationship. Sonically, “Not Sorry” contains early signs of the band’s penchant for juxtaposing soft, ethereal melodies with more abrasive, thrashing guitar work, the latter of which would become more prominent in their ensuing repertoire, as best evidenced by subsequent singles such as “Zombie” and “Salvation.”

Once dubbed by Rolling Stone as “Ireland’s biggest musical export since U2,” The Cranberries were initially overlooked in the UK, largely overshadowed during the much ballyhooed yet ultimately ephemeral mid ‘90s Britpop movement that saw the likes of Oasis, Blur, Suede and Pulp, most notably, rise to stratospheric heights of stardom. But while the vast majority of Britpop bands—with the exception of the Gallagher brothers’ outfit—stalled in their quest to penetrate the North American market in a meaningful way, the unassuming quartet from Limerick was able to secure a rather fruitful niche in the U.S., and one that endured with their next pair of releases, 1994’s No Need to Argue and 1996’s To the Faithful Departed.

A quarter-century on, Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We? remains an indispensable artifact of the band’s early career, their innocence and ambition on full display, before critical and commercial acclaim deservedly greeted them. And for those of us who continue to grieve for the late Dolores O’Riordan, the dozen songs contained therein offer at least some solace that while she is no longer with us, her inimitable voice, words and spirit are eternal”.

I am going to finish with a review from AllMusic. I wonder if the surviving members of The Cranberries (Noel and Mike Horgan and Fergal Lawler) are planning anything for the thirtieth anniversary of their debut. I hope that there is celebration. Of course, it will be bittersweet, as Dolores O'Riordan will not be with us to mark it. Fans around the world will mark thirty years of The Cranberries’ debut on 1st March:

“Title aside, what the Cranberries were doing wasn't that common at the time, at least in mainstream pop terms; grunge and G-funk had done their respective big splashes via Nirvana and Dr. Dre when Everybody came out first in the U.K. and then in America some months later. Lead guitarist Noel Hogan is in many ways the true center of the band at this point, co-writing all but three songs with O'Riordan and showing an amazing economy in his playing, and having longtime Smiths/Morrissey producer Stephen Street behind the boards meant that the right blend of projection and delicacy still held sway. One can tell he likes Johnny Marr and his ability to do the job just right: check out the quick strums and blasts on "Pretty" or the concluding part of the lovely "Waltzing Back." O'Riordan herself offers up a number of romantic ponderings and considerations lyrically (as well as playing perfectly fine acoustic guitar), and her undisputed vocal ability suits the material perfectly. The two best cuts were the deserved smashes: "Dreams," a brisk, charging number combining low-key tension and full-on rock, and the melancholic, string-swept break-up song "Linger." If Everybody is in the end a derivative pleasure -- and O'Riordan's vocal acrobatics would never again be so relatively calm in comparison -- a pleasure it remains nonetheless, the work of a young band creating a fine little synthesis”.

I am such a huge fan of The Cranberries’ Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can't We? In turns potent and powerful before revealing romance, vulnerability and passion, it is an album with so many layers and depths! It is no wonder it is still discussed and cherished today. When it turns thirty on 1st March, I think that this classic album will reach new fans. That is a great tribute to the faultless debut from the…

LIMERICK band.