FEATURE:

A Live Phenomenon

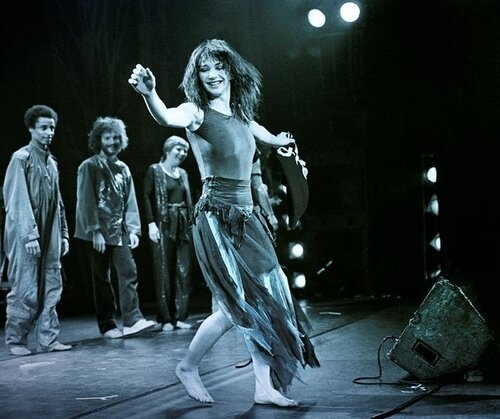

IN THIS PHOTO: Cowgirl with Pistol: Kate Bush captured during the warm-up gig of The Tour of Life at the Poole Arts Centre on 2nd April, 1979/PHOTO CREDIT: Brian Aris

Kate Bush’s The Tour of Life at Forty-Five: Marking the Anniversary

_________

THERE is a lot to unpick…

PHOTO CREDIT: Max Browne

when it comes to Kate Bush’s 1979 The Tour of Life. I am going to finish off by marking the fact that we need something to mark the forty-fifth anniversary. Whether that is a podcast, documentary or issue of a live album, the fact is that The Tour of Life was hugely important. The warm-up date happened in Poole on 2nd April, 1979. It is a really important moment in Kate Bush’s career. Where she embarked upon her only tour. Many might not know that Bush’s stage sound engineer Gordon Paterson developed the wireless headset microphone using a wire clothes hanger. Kate Bush was the first artist to use that. Also, in terms of this huge live spectacle selling out and extra dates being added. There are artists who experience this now. If you think about some of the huge live sets and concepts from female artists of today, you can trace many back to Kate Bush and The Tour of Life. I don’t think there has really been a substantial release from the tour in terms of recordings. EMI Records released the On Stage E.P. on 31st August, 1979. It featured Them Heavy People, Don't Push Your Foot on the Heartbrake, James and the Cold Gun and L'Amour Looks Something Like You as recorded at the Hammersmith Odeon on 13th May, 1979. An hour-long video of aspects of the concert was released as a home video, Live at Hammersmith Odeon, in 1981. The video featured twelve performances. In 1994, the video got a re-issue as a box-set, including a C.D. of the broadcast plus the video. Neither the E.P. or video make reference to The Tour of Life – a name used after the tour’s completion. Maybe better known as The Lionheart Tour or The Kate Bush Tour, I think there should be a cleaned up video of one of the sets. I think fans have tried to make HD videos of various sets, though there has been no official release. Many would love to get an album of The Tour of Life. As we are approaching the forty-fifth anniversary, I am thinking about that moment. When Kate Bush stepped onto the stage at Poole Arts Centre on 2nd April, 1979.

In terms of her band, we had Preston Heyman (drums), Paddy Bush (mandolin. various instruments and vocal harmonies), Del Palmer (bass), Brian Bath (electric guitar,-acoustic mandolin and vocal harmonies), Kevin McAlea (piano, keyboards, saxophone, 12-string guitar), Ben Barson (synthesizer and acoustic guitar), Al Murphy (electric guitar and whistles) and backing vocalists Liz Pearson and Glenys Groves. The Tour of Life did begin with tragedy. After that warm-up date in Poole, lighting director Bill Duffield fell through an open panel high on the lighting gallery when performing an ‘idiot check’ – looking around the venue to make sure there were no left belongings or anything that needed taking away. He would die of his injuries a week later. Mostly consisting of songs from 1978’s The Kick Inside and Lionheart (the two albums she released to that point), there was also some material from 1980’s Never for Ever – these amazing songs getting a premiere. Divided into three acts plus an encore of Oh England My Lionheart and Wuthering Heights, it was this epic set that saw Bush move from the U.K. into Europe – the first date there was 24th April at Konserthuset, Stockholm -, before coming back to London on 12th May. Aside from reduced sets on 24th, 26th, 28th and 29th April because Bush was suffering from a throat infection, she undertook these twenty-eight dates. In 2010, Graeme Thomson (who wrote the brilliant Under the Ivy: The Life & Music of Kate Bush) wrote a feature for The Guardian about The Tour of Life. The question remained as to why Bush decided not to tour again after 1979. Her 2014 residency saw her based in London:

“An independently creative woman in what was still a very male world, Bush battled against a widely held prejudice that she was little more than a novelty puppet whose strings were being pulled by some unseen svengali. As such, the tour came to be seen as a testing ground for her talent. It sold out well in advance and the BBC's early-evening magazine show Nationwide sent a film crew to cover the build-up to the opening show on 3 April at the Liverpool Empire.

Brian Southall, then head of artist development at EMI, was also there to "fly the flag" for the company. He recalls Bush being "terribly, terribly nervous, but the show was just extraordinary. We didn't quite know what we were letting ourselves in for, this extraordinary presentation of her music."

Few other artists had taken the pop concert into quite such daring territory; its only serious precedent was David Bowie's 1974 Diamond Dogs tour. There were 13 people on stage, 17 costume changes and 24 songs – primarily from her first two albums, The Kick Inside and Lionheart – scattered over three distinctly theatrical acts. Her brother John declaimed poetry, Simon Drake performed illusions and magic tricks, and at the centre was a barefoot Bush, still only 20 years old.

For Them Heavy People she was a trench-coated, trilby-hatted gangster. On the heartbreaking Oh England, My Lionheart, she became a dying second world war fighter pilot, a flying jacket for a shroud and a Biggles helmet for a burial crown. Every song offered something new: she moved from Lolita, winking outrageously from behind the piano, to a top-hatted magician's apprentice ; from a soul siren singing of her "pussy queen" to a leather-clad refugee from West Side Story. The erotically charged denouement of James and the Cold Gun depicted her as a murderous gunslinger, spraying gunfire – actually ribbons of red satin – over the stage. There was no room for improvisation. The band was drilled to within an inch of its life and Bush never spoke to the audience, refusing to come out of character. "She was faultless," says set designer David Jackson. "I don't remember her ever fluffing a line or hitting a bum note on the piano."

As the tour rolled out around the UK the reviews were euphoric: Melody Maker called the Birmingham show "the most magnificent spectacle ever encountered in the world of rock", and most critics broadly concurred. Only NME remained sceptical, dismissing Bush as "condescending" and, with the kind of proud and rather wonderful perversity that once defined the British rock press, praising only the magician.

However, the mood of the tour had been struck a terrible blow early on, after a low-key warm-up concert on 2 April at Poole Arts Centre in Dorset. While scouring the darkened venue to ensure nothing had been forgotten, the lighting engineer Bill Duffield fell 20 feet through a cavity to his death. He was just 21. Bush was shattered, and contemplated cancelling the tour. "It was terrible for her," says Brian Bath. "Kate knew everyone by name, right down to the cleaner, she was so like that, she'd speak to everyone. It's something you wouldn't forget, but we just carried through it."

Owing to demand, the tour ended with three additional London concerts at Hammersmith Odeon, following 10 shows in mainland Europe. The first night became a fundraising benefit for Duffield's family and featured Peter Gabriel and Steve Harley, for whom Duffield had also worked. They joined Bush on several songs, ending with a spirited, if rather ramshackle rendition of the Beatles' Let It Be. The second night was filmed for the Live at Hammersmith Odeon video release, which most involved agree never quite captured the essence of the Tour of Life, and the way in which it rejected the orthodoxy of the typical rock concert while simultaneously suggesting a template for its future.

Looking back, the most striking aspect is how ahead of its time the Tour of Life seemed. With its projections, its pioneering use of the head-mic, its multimedia leanings and its creation of a narrative beyond the immediate context of the songs, it was a significant step forward in the evolution of live performance. On Hammer Horror, Bush even performed to playback, an unheard-of conceit at the time but nowadays almost the norm for any show with significant visual stimuli.

PHOTO CREDIT: Max Browne

Bush seemed born to play live, but the third night at Hammersmith Odeon now appears to have been a final curtain call. Despite the very occasional cameo – her last live appearance was in 2002 with David Gilmour at the Royal Festival Hall, singing the part of the "Evil Doctor" on a version of Pink Floyd's Comfortably Numb – she hasn't toured or played a headline concert since. She came closest in the early 1990s, announcing at a fan convention her intention to play gigs in 1991; Bush is a longtime fan of The Muppet Show, and there were rumours she had contacted Jim Henson's company to discuss working with her on a new stage show.

However, the plans came to naught. Instead, her innate gift for performing was channelled into lavish videos and one patchy short film, The Line, the Cross and the Curve.

The draining experience of conceiving, organising, rehearsing, performing and overseeing the Tour of Life may have outweighed any desire Bush had to repeat the experience. "I think it was just too hard," said the late Bob Mercer, the man who signed her to EMI in 1976. "I think she liked it but the equation didn't work. These are not conversations I recall ever having with her, but I went to a lot of the shows in Britain and in Europe and I could see at the end of the show that she was completely wiped out."

The mechanics of touring certainly didn't appeal. Bush's dislike of flying has been an active ingredient in her decision not to perform on a global stage, and having endured a promotional whirlwind throughout 1978 and 1979 she found that the lifestyle – airports, hotels, press calls, itineraries, entourages and precious little solitude – sabotaged the way she wanted to live her life and conduct her career.

Others suggest that Duffield's death weighed heavily; or that the tour, which was largely self-financed, was too expensive; or that, having shown her hand so impressively, she felt no need to do it again. "People said I couldn't gig, and I proved them wrong," she said. And as Brian Southall points out, "It did pose the problem: follow that”.

It is a shame that Bush did not tour again after 1979. Even though she disliked flying, I think maybe Del Palmer was less keen on flying. Bush found travelling tiring and was aware she was out of the studio and not creating new music. In 2020, Louder told the story of The Tour of Life. It is worth reading as they discuss the preparation involved in putting it together. It is clear that this was like no other live experience:

“But that was where any similarity with a standard rock show began and ended. On an ever-shifting stage of which only a central ramp was the sole constant physical factor, Bush was a human conductor’s baton leading the entire show. As the scenery shifted through the opening Moving, Room For The Life and Them Heavy People, so did the costumes – and the atmosphere.

“I saw our show as not just people on stage playing the music, but as a complete experience,” she later explained. “A lot of people would say ‘Pooah!’ but for me that’s what it was. Like a play.”

Indeed it was – or perhaps several plays in one. On Egypt, she emerged dressed as a seductive Cleopatra. On Strange Phenomena, she was a magician in top hat and tails, dancing with a pair of spacemen. Former single Hammer Horror replicated the video, with a black-clad Bush dancing with a sinister, black-masked figure behind her, while Oh England My Lionheart cast her as a World War II pilot.

Like every actor, she was surrounded by a cast of strong supporting characters. As well as dancers Stewart Avon Arnold and Gary Hurst, several songs featured magician Simon Drake, who performed his signature ‘floating cane’ trick during L’Amour Looks Something Like You. And then there was her brother, John Carder Bush, who recited his own poetry before The Kick Inside, Symphony In Blue (fused with elements of experimental composer Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie 1) and the inevitable encore, Wuthering Heights.

But at the heart of it all was Bush, whirling and waving, reaching for the sky one moment, swooping to the floor the next. Occasionally she looked like she was concentrating on what was coming next. More often, she looked lost in the moment.

“When I perform, that’s just something that happens in me,” she later said. “It just takes over, you know. It’s like suddenly feeling that you’ve leapt into another structure, almost like another person, and you just do it.”

Brian Southall was in the audience at the Liverpool Empire. Despite the fact he worked for EMI, he had no idea what to expect. “You just sat in the audience and went, ‘Wow’. It was extraordinary. Bands didn’t take a dancer onstage, they didn’t take a magician onstage, even Queen at their most lavish or Floyd at their most extravangant. They might have used tricks and props in videos, but not other people onstage.

“That was the most interesting thing about it – her handing it over to other people, who became the focus of attention. That’s something that never bothered Kate – that ‘I will be onstage all the time and you will only see me.’ It was like a concept album, except it was a concept show.”

Two and a quarter hours later, this ‘concept show’ was done and the real world intruded once again. If there was any sense of celebration afterwards, then the main attraction was keeping it to herself. “I remember sitting in the bar after the show at Liverpool and Kate wasn’t there. She was with Del,” says Southall. “She wasn’t an extrovert offstage. There were two people. There was that person you saw onstage, in that extraordinary performance, and then offstage there was this fairly shy, reserved person.”

“I need five months to prepare a show and build up my strength for it, and in those five months I can’t be writing new songs and I can’t be promoting the album,” she once said, the closest approximation to a reason she has ever offered. “The problem is time… and money.”

Not that there wasn’t a call for it, especially overseas. America was one of the few countries where she didn’t sell records, and the idea was floated that she play a show at New York’s prestigious Radio City Music Hall so that her US label, Capitol, could bring all the important media and retail contacts to the show to see what the fuss was about. “She’s not a great flier,” says Southall. “And she wouldn’t do it.”

Even more tantalising was an offer to support Fleetwood Mac in the US in late ’79. A high-profile slot opening for one of the most successful bands in the world would was an open goal for most artists. But Bush wasn’t most artists.

“Like most support acts, she was going to get half an hour, no dancers and no magicians, so just going up there with four musicians and banging out a couple of hits,” says Brian Southall. “And she wasn’t prepared to do that”.

PHOTO CREDIT: Max Browne

I am going to wrap up in a minute. Before that, this feature from Dreams of Orgonon looked inside The Tour of Life. The reaction and reception that afforded it was ecstatic. Proof that Kate Bush was a superstar. After two albums where she felt like a cog or not someone in control, this tour was an opportunity for her to add her stamp and create something that was meaningful and true to her:

“Every night of the show got stark raving reviews from the British press. Mike Davies of Melody Maker admitted going to see Bush “more as a pilgrim than a critic,” John Coldstream of the Daily Telegraph praised her “balance between the vivid and the simple,” and former Bush naysayer Sandy Robertson of Sounds announced she had “seen the light.” There were a couple reviews from more negative quarters, mostly notably by Charles Shaar Murray in NME, who opined that “her songwriting hints that it means more than it says and in fact it means less” and “her shrill self-satisfied whine is unmistakable.” One could smugly grin at Murray for panning a critically praised and influential tour in 1979, but why do that when he invented every sexist whinge about Lauren Mayberry more than three decades early? It’s a break from the orthodoxy of Bush’s tour reviews, and thus in keeping with Bush’s ethos.

An oft-commented on aspect of Bush’s shows in reviews was its synthesis of theater and rock. This is a glib and useless description are there were many “extravaganzas” in rock music at the time, but even among them the Tour of Life broke rank. Bush had more planned for her debut concerts than simply playing her new album — she was producing a stage show, a colorful spectacle with extensive costuming, mime routines, dancers, act breaks, poetry, and elaborate set design. “I think the most important thing about choosing the songs is that the whole show will be sustained,” said Bush later. “…the songs must adapt well visually: a show is visual as well as audial, so there must hopefully be a good blend of the two.” As per usual, Bush’s way of proving herself was unorthodox. While there were other especially theatrical rock acts performing at the time (glam was the world’s loudest costume drama, and prog acts like Genesis and Pink Floyd thrived on massive setpieces, and disco and ABBA were more theatrical than they were credited for), they were mostly playing their songs live with different arrangements and more props. Bush was staging a long play, with dance acts, characters, and spoken word segments. The concerts were made by small flourishes: “The Kick Inside” got a spoken prelude by John Carder Bush with a foreboding call-and-response (Kate hauntingly shouts “two in one coffin!”), “Saxophone Song” has a saxophonist projected onto the stage, and mime Simon Drake appears decked out in white make-up as Charlie Daniels’ devil channeled through Iggy Pop. A classic component of the shows is, bizarrely, from the “Room for the Life” performances, in which Bush is rolled around in a velvet cylindrical egg (get it? It’s a uterus). She eventually departs the egg and frolics with her band during the song’s outro, giving way to Bush’s greatest performance ever as she enthusiastically calls “a-woom-pa-woom-pa-woom-pa-woom-pa-woom-pa!”, elevating the worst song on her debut album to a highlight of her career.

It was a wild time for Bush. “It’s like I’m seeing God, man!” she said enthusiastically. When she’s onstage in a black-and-gold bodysuit and blasting her bandmates with a golden, it’s easy to believe she made that comment while looking in a mirror. It takes a shot of the divine (or perhaps a deal with it?) to stage a tour of this magnitude and success while dealing with such severe drama behind the scenes? It’s no wonder Bush stayed in the studio after this, recording closer to home all the time until she set up a studio in her backyard. Even when she finally returned to the stage thirty-five years later, she made sure her venue was in nearby London. 1979 was a different time. A Labour government was feasible, and Kate Bush was regularly on TV. She plays things close to the chest now, never retiring from music but often looking infuriatingly close to it. In a way, she retired in 1979. Kate Bush the media sensation was a spectacle of the Seventies. She cordoned herself off afterwards, becoming Kate Bush the Artist. Next week we’ll look at Never for Ever, the first post-tour Kate Bush album where she unleashes a flood of ideas into the world. What does one do after the Tour of Life? In Bush’s words: “everything”.

I do wonder whether there is going to be some retrospection and celebration ahead of the forty-fifth anniversary of The Tour of Life. Ahead of 2nd April and that first date, it would be amazing to see a video release or one of the sets coming to a streaming service or physical formats. A chance to hear something truly spectacular! There was nothing like this incredible live concept. Kate Bush’s studio songs given new life and scope. Even though people have discussed The Tour of Life and given it love through the years, there is opportunity to go further. As bootlegs of the show had poor audio, something that is cleaned-up and clear should come out. There are some okay-quality videos of the sets and various performances. Nothing really that is as sharp as it could be. Such an important moment in Kate Bush’s career, we do need to celebrate The Tour of Life. Such a remarkable, dizzying and spectacular thing, The Tour of Life still hold so much power…

AFTER forty-five. years