FEATURE:

In France They Kiss on Main Street

Joni Mitchell's The Hissing of Summer Lawns at Fifty

__________

PERHAPS not placed…

IN THIS PHOTO: Joni Mitchell in 1975/PHOTO CREDIT: Norman Seeff

alongside Blue (1971) and Ladies of the Canyon (1970) as Joni Mitchell’s best albums, I think that The Hissing of Summer Lawns deserves to be. It is another masterpiece from the Canadian songwriter. It turns fifty next month. Rather annoyingly, nobody seems to know exactly when in November 1975 this album was released! To be safe, I am publishing this before 1st November, so we can mark fifty years of The Hissing of Summer Lawns at the earliest date. I think it might have been late in November but, as there is no certainty and precision, I will have to guess and be general. Before getting to a couple of features that go inside the album, I want to source this article from the official Joni Mitchell website, as they provide so many resources around the album. A host of critical reviews. Who played on the album. By all accounts, The Hissing of Summer Lawns did not get the same positivity as previous Joni Mitchell albums. That would continue with 1976’s Hejira:

“When a Brazilian photo-journalist named Wolf Jesco Von Puttkamer took an assignment in the mid-70s to document the lives of the Kreen-Akrore, a reclusive tribe of Amazonian hunters later known as the Panara, there were serious doubts about whether they'd survive the decade. The government had built a highway through their territory in '73, redoubling their fear of strangers, and the small amount of contact they'd had with the outside world in the past had decimated them with disease. Von Puttkamer found only 130 left alive.

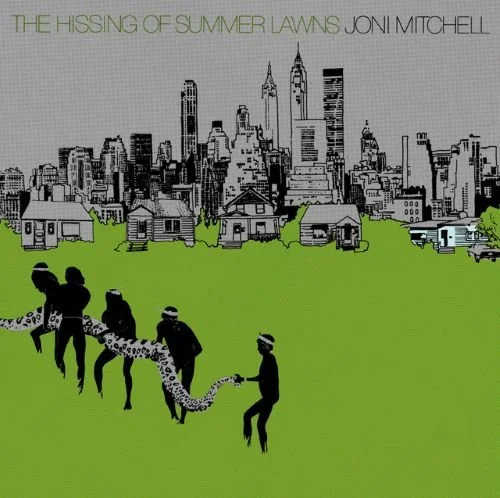

In one of the photos he took, a tiny girl camouflaged in stripes of genipap pulp peers out from a gap in the jungle. In another, the chief of the tribe grimaces as a doctor injects him with penicillin. In another, seven hunters wearing yellow headbands carry an enormous, trussed-up python back to their village from a riverbank. Published in the February 1975 issue of National Geographic, the images were seen by millions of readers, among them Joni Mitchell. While officials in Brasilia had been turning the Kreen-Akrore's paradise into a parking lot, Mitchell's live album Miles Of Aisles, with the serene momentum of an adult-oriented superstar going through an invincible phase, had cruised to No 2 on Billboard, outsold only by Linda Ronstadt's Heart Like A Wheel. At the beginning of March, Mitchell was chauffeured to the Shrine Auditorium in downtown LA to collect a Grammy for a song on Court And Spark- a pleasant accolade to place alongside its platinum disc. But the python and the boys in the headbands must have stirred something, because she got out her ink, drew the photo from National Geographic and incorporated it into the cover art of her next LP. In doing so, she set in motion a chain of events that shattered the calm, darkened the skies and left her seething about the criticism she never saw coming.

The Hissing Of Summer Lawns is many things. It's an exclusive peek behind the curtain of palm trees that protects the super-wealthy and the super-bored. It's a set of 10 musical pieces that are at times melancholy, graceful, fine-woven and inscrutable. It's a dossier of sophisticated observations on women's material victories and defeats as they rely on, resent or revolve around their men. Above all, it's an LP that documents the lives of an endangered species that knows little of worlds beyond its own: the indigenous tribespeople of American suburbia. On the embossed sleeve, Mitchell transposed the giant snake to a fettucine-green landscape that might have been a modern-day urban park. The skyscrapers of a metropolis towered in the distance. Lined up in front of them, occupying the space between the businessmen and the bushmen, a row of bungalows stood like tanks before an army, guarding the city's perimeter. Mitchell's motif of the summer lawn was both impressionistic and sociocultural. The incongruous elements of the cover art combined in a visual pun. The hissing sound was made by sprinklers, but a serpent can thrive in a suburban dream-home, coiling itself around a marriage.

Joining some of the dots was "The Jungle Line", the album's second song, in which Mitchell traced direct connections from Africa to the jazz clubs of New York, imagining their crammed, noisy cellars as canvasses painted by Henri Rousseau. A primitivist best known for his tropical jungle scenes, Rousseau might well have designed a club décor of "ferns and orchid vines" (as well as putting a "jungle flower" behind the waitress' ear), but the snake that Mitchell notices in the jazz band's dressing-room is only a figurative cousin to the real ones in Rousseau's The Snake Charmer. It's a "poppy snake" - in other words, the heroin that comes into the city via the trafficking routes that lead back to another humid, vine-thick jungle. To get deeper into the heart of darkness, Mitchell hitches the venue's wild clientele ("cannibals of shuck and jive") not to a backdrop of jazz horns, but to pummelling Burundi drums and the electronic growl of a Moog. A totally new event on a Joni Mitchell record, "The Jungle Line" was conceptually provocative and years ahead of its time. The primitive met the avant-garde in the ritual of after-hours safari, and everyone from Paul Simon to Adam Ant was galvanised by the rhythms.

But as the LP cover reminds us, to travel from jungle to city, the primitive must first pass through the suburbs. In isolation and affluence, the suburbanites scatter themselves like plush velvet cushions behind their gadgetry and emotional shields, while Mitchell, with penetrating eye and paintbrush, sees something slithering in their neatly mown gardens. How self-negating are the concessions, she seems to conclude, that yield and are yielded by these unhappy families. Her "third-person lyrical portraits of damaged and unsympathetic characters," as Elvis Costello once called them, now begin to make their presence felt. They change the tone of the album completely, and with them disappear any realistic prospect of another singer-songwriter confessional. What exactly appears in its place - an air of cold detachment? A sleight-of-hand elegance? An artistry so rarefied that some people don't react to it while others can't stop overdosing on it? - has been the subject of debate for four decades.

For example: Edith, picked up last night by a crime boss, awakes in his bed with a song going through her mind. The title eludes her, but her thoughts quickly turn to the man by her side. She won the contest to be his prize for the evening, beating off the competition of older girls, and the criminal empire he runs is not hers to question. She locks eyes with him across the pillow. As the song ends, Mitchell seems to suggest they're as amoral and desperate as each other: a perfect gangland match. "You know they dare not look away," she sings, holding one of the album's longest notes for as long as the two of them can stare without blinking. And that, sure enough, is one way of hearing "Edith And The Kingpin".

But another way is to listen to the musicians – all of them, or as many as you can – who, far from being emotionally detached, bring sweetness and warmth flooding into the song from all corners. This way of hearing involves smiling with eyes closed as the trumpet on the left is joined by a flute on the right, and once they've held their notes for nine seconds, an electric piano ("fresh lipstick glistening") plays a rippling trill so exquisite that a nearby electric guitar appears to sigh with bliss. Another example: "Don't Interrupt The Sorrow", which follows, has often been described as a stream-of-consciousness jazz poem, making it sound like a text of abstruse intellectualism that only someone with a triple First in Classics and Oriental Languages would enjoy. Don't believe a word of it. Cajoled along by Wilton Felder's inventively rubbery bassline, "Don't Interrupt The Sorrow" is a cavalcade of musical delights. Guitarist Larry Carlton's feather-light glides up and down his fretboard provide so many gorgeous moments that Mitchell stops singing and lets him form them into a solo.

Minutes later, when we meet the highmaintenance Southern belle Scarlett ("Shades Of Scarlett Conquering"), we can count, by all means, the cost of what she loses with her impossible demands while she adheres to the doctrine she absorbed from Gone With The Wind- but we mustn't forget to swoon to Dale Oehler's heavenly string arrangement or luxuriate in the dreamy pattern of piano notes that Mitchell reiterates with her left hand. The Rolling Stone reviewer in 1975 who claimed that the album had "no tunes to speak of' evidently missed the wood for the trees; most of the songs are inundated with instrumental parts of aching loveliness, be it Chuck Findley's Bacharach-ian trumpet on the title track or his flugelhorn's haunting three-note refrain on "The Boho Dance", and their cumulative importance is as absolute as any vocal or lyric. However, as Mitchell would learn, finding not a single tune on The Hissing Of Summer Lawns wasn't the most scathing accusation the critics in America would level.

There are two more songs about suburban marriages in the album's second half, and at the end of each one the wife makes a pragmatic decision of sorts. In the title track, an unnamed woman lives as a virtual prisoner on her husband's hillside ranch ("She patrols that fence of his to a Latin drum"), but chooses to stay because there's just enough value in their expensive home to compensate for the poverty of her dreary days. As per Mitchell's album concept, the soothing hiss that the woman can hear from her balcony has worked its mesmeric effect. When it doesn't, the result comes as a shock. A high-ranking executive on a business trip to New York ("Harry's House/Centerpiece") has an erotic daydream about his wife when she was younger ("Shining hair and shining skin/shining as she reeled him in"), before snapping out of his reverie - and we aren't prepared for it - to reveal in the last few lines that she asked him for a divorce that morning. How old is the woman? Her age isn't specified. Old enough to be bored out of her mind with her husband, that's all we need to know. Old enough to be conscious of the moisturizing lotions and the march of time. "All those vain promises on beauty jars, "Mitchell sings in "Sweet Bird", the next song, just in case a middle-aged divorcee might fancy she's escaping into a rainbow. "Calendars of our lives, circled with compromise."

Mitchell, unmarried herself, lived behind wrought-iron gates in her 1920s Bel Air mansion with her boyfriend and drummer, John Guerin. When the gatefold sleeve of Hissing... was opened, there she was, floating on her back in the secluded Eden of her swimming-pool, while 30 lines of album notes, starting somewhere above her right knee, made it clear she was elated with the product inside. "This record is a total work conceived graphically, musically, lyrically and accidentally- as a whole. The performances, were guided by the given compositional structures and the audibly inspired beauty of every player. The whole unfolded like a mystery." A mystery to be lapped up by hundreds of thousands of armchair sleuths who hung in her every word. But something went wrong. The verdict was not measured out in superlatives this time. Critics dipped their adjectives in scorn (“narcissistic”, “pretentious”, “sometimes so smug that it’s downright irritating”) and her manager had to hide the reviews from her. With its jazz overtones and clear shift away from autobiographical writing, the LP left many fans disappointed. Internet book reviewers condemn a much-hyped novel by saying they “couldn’t relate to any of the characters”. The problem with the album was that some people couldn’t relate to the fact that there were characters at all.

In the 40 years since its release, it’s been place in a much more favorable light. Mitchell was touched when Prince listed it as one of his favorite albums in the 80s. Bjork, Morrissey, and George Michael all sung its praises. Elvis Costello hailed it as “the masterpiece of that time” when he wrote about Mitchell for Vanity Fair in 2004. It’s now celebrated for the very qualities that 70s listeners found hard to tolerate: the icy stillness, the special composure, the delicate balance of colors, the manicured refinement, the considered reportage”.

I will move to Albumism and their forty-fifth anniversary salute of Joni Mitchell’s The Hissing of Summer Lawns. If you have not heard this album, then I would suggest that you spend some time with it now. Even if critics were somewhat cold to upon its release, there is no denying it brilliance. It still sounds phenomenal years after I first heard it. One of the essential Joni Mitchell albums:

“Mitchell’s fans had acquired a taste for gossip. Taylor Swift isn’t the first songwriter to use her personal life as grist for the mill. Mitchell’s laundry list of lovers includes Leonard Cohen, David Crosby, Graham Nash, James Taylor, and others. Fans had become accustomed to her songs being informed by the highs and lows of those relationships. Much of the ballyhoo (or lack thereof) was around the shift away from more popular works like Blue (1971) and her previous studio album Court and Spark (1974) that mined these experiences. That is to say, Mitchell had no intention of spilling the contents of her heart like a purse turned upside down this time.

“People started calling me confessional,” Mitchell lamented about the response to Blue, “And then it was like a blood sport. I felt like people were coming to watch me fall off a tightrope or something.” And so began the moratorium on allowing the public to live a vicarious love life through her.

Furthermore, Mitchell as an artist is adventurous and musically itinerate. Sentencing her to continue making different permutations of Blue time and again might have put her in an early grave. She needed to follow her muse, and it was very much a moving target. Hissing dabbles in world music, defiantly undiluted jazz, and incorporates synthesizers for the first time. On one hand, this is truly exciting for an artist. On the other, it drove Asylum Records to drink.

Asylum co-founder David Geffen was actually Mitchell’s roommate for a time. Though Geffen repeatedly encouraged her to write hits so she could “sell a lot of records,” he says she laughed the idea away. Roberta Joan Anderson could not be any less concerned with hits. It didn’t matter to her that Hissing’s esoteric lean made choosing a single nearly impossible. This was the album she wanted to make.

The label issued “In France They Kiss On Main Street” as a 7-inch in the winter of 1976. The rollicking release is full of youthful abandon, not unlike some of the L.A. Express-backed workouts on Court and Spark. Here, the verses scrawl romantic, devil-may-care imagery on the wall almost faster than the listener can take them in. Friendly ex-flames Nash, Crosby, and Taylor join her all-star background chorus for a fun time. In total, “France” flirted with Adult Contemporary radio for a couple months until it reached #32. But then it lost interest in the pursuit and went off to sweet talk someone else.

The title track of the LP begins its flip side with a lustrous, afternoon groove. Electric piano and Moog bass guarantee a mellow mood. The song is rife with understated musicianship, like the lazily purring horn line that follows the bridge, curling on the ground like an overfed housecat seeking attention. And every time Mitchell sings “summer lawns,” she drags its sibilance behind her like the tail of a serpent. Her perception is keen, and delivery slit-eyed. The exhibitionist has become a voyeur.

It was revealed in 2012 that Mitchell wrote “The Hissing of Summer Lawns” about renowned musician José Feliciano after visiting him and his new wife at their home in the San Fernando Valley. Attaching the lyric to Feliciano, famously blind since birth, gives a context that changes the lighting on its opulence and elitism (“He gave her his darkness to regret / And good reason to quit him / He gave her a roomful of Chippendale / That nobody sits in / Still she stays with a love of some kind / It's the lady's choice”).

Mitchell again casts a questioning eye on a relationship in “Edith and the Kingpin.” The three-act short story has no chorus, but is carried by a curious melody rolled through a winding path of jazz chords. In it, an underhanded figure in a small town sets his sights on a soon-to-be-corrupted young ingénue (“Women he has taken / Grow old too soon / He tilts their tired faces / Gently to the spoon”).

Answering the imagined questions of salivating gossip hounds, Mitchell told Mojo Magazine, “Part of it is from a Vancouver pimp I met and part of it is Edith Piaf. It's a hybrid, but all together it makes a whole truth. Basically, I am trying to present the human truth, but did [those things] happen specifically to me? What does that matter?” That’s how an intellectual tells one to mind one’s own damn business.

If that stung any, focus on the “little black dress” that Mitchell’s voice then slips into for the Hendricks-Edison composition “Centerpiece.” In this dream sequence, Mitchell indulges her Cotton Club fantasy shimmying as if to drive a hooting audience as mad as possible. It’s in the way she saunters up to all the flat thirds in the melody, shamelessly milking all the soul that can be gathered from them. The ‘50s jazz tune gets spliced into the center of “Harry’s House,” itself a compelling split-screen depiction of a marriage with its intimacy waning.

The Hissing of Summer Lawns didn’t have quite enough jazz to vie for Recording Academy honors in that category. It had just enough to scare off the timid contingent of her pop, rock, and folk listeners. It scored a GRAMMY nomination for Best Female Pop Vocal Performance, but was predictably passed over in favor of Linda Ronstadt that year.

Genuinely unconcerned with her records’ commercial performance, Mitchell would swim out into deeper jazz explorations over the next several years. Her pairing with kindred musical spirit Jaco Pastorius would define Hejira (1976). Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter (1977) would push even further past the edge of wonder. By 1979, jazz legend Charlie Mingus chose Mitchell to complete the last compositions of his lifetime on an album named after him”.

I am going to end up with a review from The Quietus from 2020. They marked forty-five years of Joni Mitchell’s seventh studio album. The Hissing of Summer Lawns contains some of Mitchell’s best songs in my view. In spite of the fact it was a relative chart success in 1975, it did not get the critical acclaim that it deserved. I am glad that there has been fonder regard in years since. It is a wonderful album:

“‘In France They Kiss On Main Street’ stands as a stepping stone between what Mitchell had been and what she was about to become. It would not have been notably out of place on Court And Spark. But ‘The Jungle Line’, with its thudding tribal drums and beat poetry incantations, certainly would. Now, there are, let’s say, issues with Mitchell and race. Not just the sleeve of Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter (1977), which one might generously explain away as theatricality in art, but her subsequent, jaw-dropping remarks about it. And to invoke the jungle, and Rousseau – whether he of the noble savages, or he of the Primitivist art; it proves to be the latter – on “Safaris to the heart of all that Jazz” in Harlem is, in today’s wince-inducing word, problematic. And yet. So evocative is its sorcery, so piercing of history’s sweep the lyric, that if one cares to justify it, one could say it is descriptive of the products of an attitude rather than an example of that attitude. And if one doesn’t, one may simply acknowledge both its uncomfortable stereotyping and its singular redolence and atmosphere, and accept that chipping away at the clay feet of great art for the purpose of bringing it down altogether is a kind of spiritual vandalism – as if the entire past must be slung out for failing to come up to code in the present.

The safari seems a preliminary excursion, but it isn’t. It travels by an unexpected route to the same set of views, which is female life seen both from the inside and the exterior. ‘The Jungle Line’’s barmaid is sister under the skin to Edith, she of the languid, lovely ‘Edith And The Kingpin’. The Kingpin is a small-time Mr Big, a local potentate, who has fixed upon Edith as his bedmate, the latest in a line of women who “grow old too soon”, raddled by cocaine and the terrors of their incumbency. Chosen, Edith has no choice. Taken, she must take what she is given. She is woman as vassal, no more free in her American town than her equivalent falling under the eye of a feudal village’s liege lord. No more free than the lavishly kept wife in the title track – who might be Edith, years on, prisoner of the man she’s captured – pacing the barbed wire perimeter of her ranch house like the caged animal she is. Or is she? Is it that liberty is impossible, or that she imprisons herself? “He gave her his darkness to regret/And good reason to quit him… Still she stays with a love of some kind/It’s the lady’s choice."

Here she is again, or again, her subcutaneous sister, in ‘Harry’s House – Centerpiece’, yet another of the post-Impressionist wonders Mitchell daubs onto the album in loose brushstrokes that coalesce with magical precision into perfect pictures; and every last one of those pictures has its shadows and it has some source of light. Here is Mad Men, three decades early. Harry in the city, surrounded by glamour and sexual opportunity; wifey in the suburbs, surrounded by dead air. And with astounding artfulness, Mitchell places at the heart of her own song a cover version, the swing-jazz standard, ‘Centerpiece’, in which the singer’s “pretty baby” is lauded as, quite literally, a piece of furniture around which his household is to be assembled. In the gap between 1958, the year of the song’s composition, when its subject was evidently intended to feel delight at such a prospect, and 1975, Mitchell unpicks how it feels to become a trophy. Edith, Harry’s wife, the “lady” of the summer lawn: all are prized possessions who learn the hard way just what it is to be acquired, when you think it’s you who’s making the catch.

Mitchell never makes things simple. Nor needlessly complex. The music on these songs flows like water running downhill, switching this way or that not for the sake of it but because it must. Its course is unpredictable and ineluctable; once followed, it could not, you sense , have gone any other way. The same is true of the feelings and images it carries along. They are as plain and as complicated as the lives they invoke. So there is no easy dichotomy whereby women at liberty are happier than women trapped by men, or by themselves. Freedom has its own hazards. “Since I was seventeen/I’ve had no one over me,” snarls the narrator of ‘Don’t Interrupt The Sorrow’, the scene of a fierce and terse battle of the sexes in which ancient, Abrahamic patterns of domineering and resistance play out via the mores of the day. Religion clutches at everything. ‘Out of the fire like Catholic saints/Comes Scarlett and her deep complaint.” Woman as something wounded. Woman as something bloody and unbowed. Woman as something red, aflame and dangerous. This is ‘Shades of Scarlett Conquering’. A lambent piano ballad, invoking Gone With The Wind and depicting a creature of unblinking will: ‘It is not easy to be brave/Walking around in so much need… Cast iron and frail/With her impossibly gentle hands/and her blood-red fingernails.’ Mitchell unfolds the femme fatale from the inside, in the most delicate and ingenious reverse origami, and makes you quiver at the truth of it”.

It is a bit strange that there is no certainty regarding exactly when in November 1975 The Hissing of Summer Lawns was released, I am going to play it safe and say 1st, even though it was likely later in the month. It doesn’t really matter that much. What does matter is heralding this masterpiece. I was keen to show my appreciation for…

SUCH a brilliant album.