FEATURE:

Beneath the Sleeve

Charles Mingus - Mingus Ah Um

__________

IT is not often that…

IN THIS PHOTO: Charles Mingus shot at Columbia 30th Street Studio recording Mingus Ah Um in May 1959/PHOTO CREDIT: Don Hunstein

I include a Jazz album in this feature. For Beneath the Sleeve, I am including Charles Mingus’s Mingus Ah Um. It was released in October 1959 by Columbia Records and it was Mingus’s first recorded for Columbia. The title is a corruption of an imaginary Latin declension. Mingus Ah Um album was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2013. It was ranked 380 on the Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. That is a bit of brief overview, with a nod to Wikipedia. I am going to start out with Sounding Out! and their background about Mingus Ah Um. How the album is an ethics of care in Jazz:

“Released in 1959 in the same orbit as Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue (August 1959) and Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come (October 1959), Charles Mingus’s Mingus Ah Um (September 1959) showcased Mingus’s range both as a composer and bassist. Intimate both in its sound and session composition (only seven sessions players worked on the album), the album provides a purview into Mingus’s commitment to the idiomatic (“interconnected”) and collaborative nature of the black jazz tradition and the stakes of/for black art and artists. His investment in jazz’s black idiomatic structure stood at odds with the increasing importance of the singular jazz man to the marketing of jazz music.

Works like Mingus Ah Um prompt listeners to listen attentively to collaboration and collaborative efforts, both in the setting of a jazz ensemble/collective and in the historicity of black (jazz) men caring for one another. While the imposition of white gender prerogatives sometimes foreclosed intimate, homosocial (same-gender, social) relationships between black jazz men that revolved around what Christina Sharpe terms in In the Wake: On Blackness and Being as an “ethics of care,” Mingus Ah Um is not only an ode to black jazz ancestors and elders, but performative of Mingus’s deep care about the black jazz tradition and its futurity.

In histories of jazz, Charles Mingus is often characterized as volatile and dismissive of young black jazz artists. His purported critique of neo-jazz movements of the late 1950s and early 1960s, like the free jazz (“The New Thing”)/avant-garde jazz movement, narratively put him at odds with emerging jazz artists like Ornette Coleman and Miles Davis. But as demonstrated by Mingus Ah Um, Mingus profoundly cared about black jazz men and the future of black jazz music. Given these histories, what would it mean for listeners to not dismiss

Mingus altogether, but hold in tension his anxieties, deemed dogmatic and peremptory, with his often careful and honorific sonic confabulation with black jazz men? How does re-listening to Mingus Ah Um make us empathetic to Mingus’s pursuit in preserving a waning black jazz tradition that was ever increasingly ridiculed and mocked (by way of anti-blackness) for its presumed anti-intellectualism and placation to whiteness? The undercurrent of Mingus’s care is not always expressed in histories or interviews, which begs the question: what is rooted in, yet exceeds the autobiographical, when we listen?

When listening to Mingus Ah Um the album’s ethics of care might be heard most explicitly on tracks like “Fables of Faubus,” a protest song in the most righteous sense, aimed at Orval Faubus, the former Arkansas governor who deployed the state’s national guard to barricade Central High School in Little Rock from the threat of integration (which is also to say the threat of miscegenation). A tune steeped in dissent and once with lyrics that made Columbia ask Mingus to re-record the tune: “Boo! Nazi Fascist supremists!/Boo! Ku Klux Klan (With your Jim Crow plan).” (“Original Faubus Fables,” Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus, 1960)

We have often confused Mingus’s care for the future of jazz music and black jazz artists for an ornery and grouchy disposition. He was quite cognizant of the fraught relationship black jazz artists had with the financialization of black performance, writing in his autobiography Beneath the Underdog: His World as Composed by Mingus that the music industry was a “system those that own us use. They make us famous and give us names—the King of this, the Count of that, the Duke of what! We die broke anyhow—and sometimes I think I dig death more than I dig facing this white world”.

Marking its sixty-fifth anniversary last year, Albumism heralded a Jazz masterpiece that came out on 14th September, 1959. Maybe a lot of people reading this would not have heard the album, though I feel Mingus Ah Um should be heard by everyone. It is a magnificent work that is future-looking, but it also throws back to an older time. I first heard Mingus Ah Um recently and wanted to shine a light on it here:

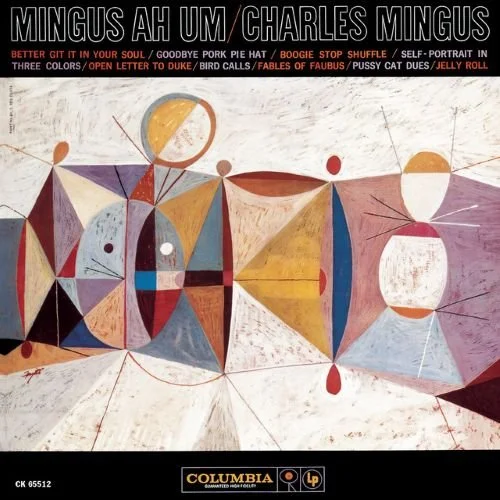

“Mingus’ work of genius sports a stunning abstract cover by legendary graphic design innovator S Neil Fujita—part of a concerted effort on Columbia’s part to keep level in the cool stakes with Blue Note. Francis Wolff’s iconic photography and Reid Miles’ typography had given Blue Note the lead, but the abstract design that graced Mingus Ah Um mirrored the freewheeling jazz spirit that lay within the grooves of the vinyl.

A glimpse at the tracklist demonstrates exactly the breadth of Mingus’ compositional focus. There’s the self-reflection of “Self-Portrait In Three Colors,” the skewering of those at the heart of injustice on “Fables Of Faubus” and the inspiration found within the jazz community of “Open Letter To Duke.” Such diversity of inspiration manifests in the diversity of dynamics in the tracks.

But those subject matters allied to his infamous brooding temperament might lead you to think the music contained within was sonorous or intrinsically serious and joyless. What Mingus Ah Um does brilliantly is take those darker recesses of the world and wraps them up in a joyously exuberant roll call of tunes that not only take their cues from jazz, but also add the slightest hints of gospel and the blues. It is, in effect, a glorious gumbo of Black music up to that point.

“Better Get Hit In Your Soul” is the most obvious case in point. At times it shuffles along, before breaking into a surging juggernaut swinging as it careers into view, but beneath the music are shouted exhortations from Mingus himself. Like the call and response of early blues or the moment the spirit moves in church, he yells his testimony from somewhere deep in the mix. Throughout the changes in tempo and instrument, one thing abides—a refreshingly healthy dose of fun. It feels the opposite of other, intensely earnest recordings of that year (and beyond).

The elegiac “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” hits precisely the right somber tones in tribute to the recently departed Lester Young and “Boogie Stop Shuffle” sounds like the (complex) theme tune for a detective show or film noir. An expected change of tone and feel comes with the introspection of “Self Portrait In Three Colors.” Starting with a mournful mellow mood, it meanders into a wistful, louche reflection of the artist.

Hard swinging platonic love letter to Duke Ellington “Open Letter To Duke” does exactly as you might expect—it blurs the lines between the orchestrated precision of Ellington’s compositions and the freer from of jazz that swept through the genre, while that same hard swinging tribute comes with “Bird Calls” as the sax goes through its gears in tribute to the trail blazed by Charlie Parker. But what follows next is one of Mingus’ most intensely political compositions: “Fables Of Faubus.”

It has to be said that when I first listened to the track, its vaguely comedic tones made me smile from ear to ear. To learn later that it had been written for Arkansas governor Orval E Faubus, who notoriously brought in the National Guard to ensure that nine black children couldn’t be integrated into a Little Rock school, left me agog. But listening to it again showed the music in a different light—its intent wasn’t comedy, it was ridicule. Ridicule for a man so deeply entrenched in vile racism that Eisenhower sent the 101st Airborne Division of the US army to shut his plans down.

In 2003, Mingus Ah Um was chosen by the Library Of Congress to be added to the National Recording Registry alongside other epochal, life-changing albums and it deserves its place entirely. The beauty of these recordings (and Mingus in general) is that they acknowledge the debt of previous musicians and art forms, while forging a new way to navigate the tensions between written composition and improvisation.

That he was a volatile figure should be expected given the circumstances he grew up and played in, but his music was salvation both for him as composer and for anyone who listened. Salvation that could only come from someone steeped in blues and gospel traditions—the sweetest of salvations”.

I am going to head back to 2002, and a review from Pop Matters. An extraordinary and seminal album that is hugely affecting and will instantly move you, I hope that this feature has helped go beneath the sleeve of the 1959-released masterpiece. You do not need to be a Jazz fan or know about Charles Mingus to love this album:

“The whole thing was recorded by Teo Macero in two days, May 5 and 12, 1959. This was Mingus’s first record on Columbia, so (Mingus being Mingus) he went all sideways; instead of calling in a bunch of well-known all-stars, he pulled together a young hungry band from his Jazz Workshop project: Booker Ervin and John Handy on saxophones along with older collaborator Shafi Hadi, Dannie Richmond on drums, and the amazing Horace Parlan on piano, with Mingus vets Jimmy Knepper and Willie Dennis alternating on trombone. (Compare Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, released the same year, with its ultra-hip lineup.) The fire and commitment of the young band is amazing — everyone except Mingus was 33 or younger — and the sound is impeccable, especially in its remastered CD version.

“Better Git It in Your Soul” is the first track, and has become the most daunting classic in jazz. It starts, appropriately, with Mingus on bass playing a strong figure that somehow sets the pulse for the entire 6/8 piece, which bursts into flower at the 18-second mark and never looks back. It’s a church revival meeting that somehow seems entirely secular; Mingus is testifying out loud, “Oh, yeah!” but it seems more like the Temple of Music than any religion dedicated to a deity. All the saxophones have ace solos, but the insane pulse carries the piece, with Parlan and Richmond hammering away in some kind of trance. Parlan gets high marks for his solo breaks all through the record — this is especially amazing considering he only had the use of two fingers on his right hand. He’s the Pete Gray of jazz, and a motha. And when the piece deconstructs itself at the 3:45 mark, with handclaps backing Ervin punching out the funkiest sax piece of all time, it just may be the origin of the funky breakdown in music.

The slow pieces are devastating: “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” is glacial in celebrating Lester Young, but its momentum is undeniable, and “Self-Portrait in Three Colors” is what the band will be playing when we’re all ushered into that great jazz club in the sky. “Fables of Faubus” is a devastating burn on Orville Faubus, the racist cracker asshole governor of Arkansas; it lacks Mingus’ hilarious lyrics here (thanks, probably, to Columbia’s legal department), but the idea of a lurching stupid man standing in the way of progress and harmony is carried through perfectly in its stop-start groove. And the fast pieces are so amazingly fast that they are untouchable; “Boogie Stop Shuffle” is like speed metal, kinda, except without the metal part, and the be-bop pace of the Charlie Parker tribute “Bird Calls” would be intimidating for any other band.

But here is why this record is crucial: it is the template for all later album statements. Thelonious Monk had been the first jazz composer to really try to maintain a personal tone on his albums in the late 1950s, but a strong case can be made that Mingus Ah Um was the first record to really feel a musician’s personal stamp all the way through. I’m not saying this is a concept album, although his tributes to Parker and Young and Duke Ellington and Jelly Roll Morton (and Faubus) do give it a certain unity. But think of any album released before this one, by anyone, in any genre: weren’t they all just collections of songs? Mingus Ah Um is a unified work, a novel as opposed to a volume of short stories, a manifesto that derives as much from its sequencing and total impact as it does from the individual performances and songs.

Well, okay, Kind of Blue and The Shape of Jazz to Come also came out in 1959. But isn’t it interesting that these three groundbreaking albums were all recorded at more or less the same time? For many reasons, this was the defining year in modern music history — this was the first time that musical artists were treated like artists instead of hit machines. So we’ve got the historical significance thing, the beauty and technical virtuosity thing, and the soulful thing covered. But what it really comes down to is this: This Record Is Absolutely Freakin’ Amazing In Every Single Way I Can Think Of, and it’s never ever bored me, not even once.

I guess it woulda been cooler to pick the Minutemen record, but I’ve made my choice. So there. You guys aren’t actually going to make me give up all my other records, are you?”.

Mingus Ah Um is a staggering work that ranks alongside the absolute best and most important Jazz records ever released. I think that it is also timeless. Some albums from the late-1950s date and can lose their power. However, Mingus Ah Um still sounds extraordinary and vital…

TO this day.