FEATURE:

Golden Year

David Bowie’s Station to Station at Fifty

__________

I was going to use this feature…

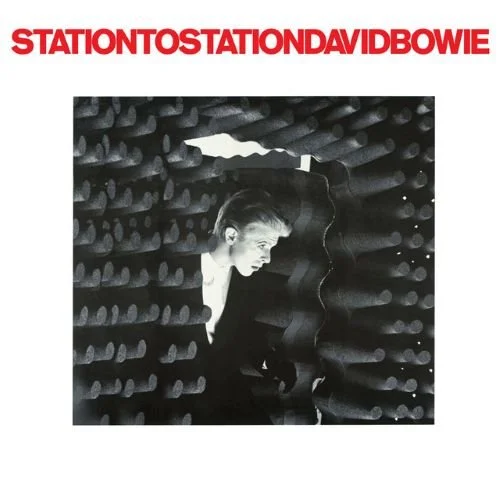

IN THIS PHOTO: David Bowie in 1976/PHOTO CREDIT: Andrew Kent

to discuss David Bowie and the fact that it has been ten years since he died. On 10th January, we will talk about David Bowie. It was a huge shock in 2016 when we heard the news. I know that people have written about that anniversary and will write about it. Instead of writing about that, later this month, one of his classic albums turns fifty. That is Station to Station. Released on 23rd January, 1976, it was Bowie’s tenth studio album. In terms of dynamic and stylistic shifts, perhaps this was one of the biggest. 1975’s Young Americans was influenced by American R&B and Soul. Bowie's performance persona of the Thin White Duke, he kept the Funk and R&B of his previous album but drew in Electronic and Krautrock. In terms of Bowie’s mindset during the time, he was heavily into drugs and could not recall most of the production. Exceptional gaunt and thin, it is amazing that he managed to make such an extraordinary album! In terms of its format and length, starting out with the extraordinary title track, it then moves into Golden Years. Ending with Wild Is the Wind - lyrics by Ned Washington and music by Dimitri Tiomkin -, there are fewer tracks than previous albums, but they are more expansive and some would say experimental. Before getting to some features and retrospectives about Station to Station, MOJO revisited David Bowie’s masterpiece. It is amazing thinking about cohesive and nuanced Station to Station is considering how David Bowie was living at the time:

“In August 1975, after the filming of The Man Who Fell To Earth had finished, Bowie rented a house at 1349 Stone Canyon Road in Bel Air, a secluded 1950s-built property with a mock Egyptian interior. From here, he pulled together a team to record his next album: Harry Maslin, who’d worked on the Fame session in New York, was recruited as producer, while guitarists Carlos Alomar and Earl Slick, plus Fame drummer Dennis Davis, and bassist George Murray, provided the core of the group. After two weeks’ rehearsals, the group checked into Cherokee studios in Hollywood. One of the first songs to emerge was Golden Years, a sinuous soul groove that took up where Young Americans had left off. It was premiered on November 4 on ABC TV’s Soul Train, reflecting David’s new kudos within the US soul community.

By now, Bowie was surviving on a diet of milk and cocaine, with the odd vegetable thrown in, and regularly went without sleep. Though only six songs emerged from the sessions, they amounted to some of Bowie’s finest work. The title of the book of short stories he’d begun writing while shooting TMWFTE, titled The Return of The Thin White Duke, made its way into the opening line of Station To Station, an epic 11-minute piece that moved through a series of moods – sometimes dark, melancholy and mysterious, elsewhere funky and euphoric – with allusions to the Kabbalah, cocaine and, in its title, the Stations of the Cross, the popular representation of Christ journeying towards his crucifixion.

The beautiful Word On A Wing, meanwhile, explored a more conventional Christian, or perhaps Buddhist, theme; Stay was a trippy funk-out with soaring psychedelic soul guitar; and TVC15 fused New Orleans piano and futuristic soul, telling the tale of a woman devoured by a television set. The final track, a cover of Wild Is The Wind, the 1954 film theme memorably covered by Nina Simone in 1966, bookended the album in magnificently contemplative and dramatic style, completing a record exuding strangeness and imbued with layers of mystery. Perhaps it was all a lucky accident: David later admitted he had few recollections of recording the album, bar shouting his idea for a feedback part to Earl Slick. Regardless, in an almost peerless run of late 70s albums, Station To Station is still one of the most beguiling stopovers. Next stop, Berlin”.

In a fascinating essay from The Quietus, they looked back on Station to Station on its forty-fifth anniversary. The 2020 feature is a great read. I have selected some segments from it. I am sure that there will be quite a lot of fiftieth anniversary features about this extraordinary album:

“More than on any other Bowie album in a career built on exploring the theme from any number of angles, the idea of decadence is at the heart of Station to Station. If Young Americans, his previous album, had examined the post-Watergate rottenness infecting the once-great nation he’d recently adopted as his home, then on Station to Station he turns his gaze fully inward upon his own condition, and finds the creeping decay at work there too. It’s a pre-punk album, not just chronologically (recorded in ten days at the end of 1975), but in recognising the hollow, bloated state of the rock aristocracy of which Bowie was a part, especially in contrast to the social upheaval and economic recession going on in the real world, wherever that was. Punk was a response from the kids on the street, but Bowie was part of the problem, and he knew it, tall in his room overlooking the ocean, staring out through a blizzard of coke and knowing it was all coming crashing down.

Ah, yes: cocaine. The proverbial Peruvian is all over this record, but not in an over-produced, airbrushed Rumours way. Station to Station is shiny but spare, harsh; it captures the jagged edge, the exquisite balancing act between the high and the comedown, and the sense of feeling hugely emotional at the same time as feeling completely numb and detached that is a typical symptom of fast white drugs (speed, E, coke). Similarly the intellectual grandstanding, paranoia and occultism, barely masking an inner desperation; having made a career out of wearing masks, inventing personas, analysing his emotions from a distance and then acting them out, Bowie seems desperate for a way out of his situation. Early in his career, under the influence of Lindsay Kemp, he made a short film called The Mask, in which a mime artist puts on a mask that then takes him over. By 1975 for Bowie the parable had come true. Lauded, wealthy, trapped in the social whirl of an affluent and fashionable Los Angeles jet set, reputedly existing on a diet of cigarettes, orange juice and cocaine and immersing himself in mysticism, conspiracy theories, the occult and an increasing fascination with right-wing ideologies, Bowie was fast becoming the epitome of the Decadent Man. Yet Station to Station is far from the work of an artist in decline. Rather, it extends the Philly funk of Young Americans into weirder, colder territory, and marks the beginning of the period of radical musical reinvention and rigorous introspection that would continue through the Berlin period and the more celebrated Low and "Heroes" albums.

Like the Duc Des Esseintes- the original Thin White Duke? – in Huysman’s 1884 novel A Rebours, Bowie has become jaded beyond belief, too numb and sated to be moved by any but the most extreme sensations. So far gone, so alienated from his own feelings is he that what he craves more than anything else is an authentic experience. Eventually he would realise this by stripping away all artifice and moving to Berlin, but here he still attempts to contrive genuine emotion, to convince himself by dint of a bravado performance. As if acting on ‘Young Americans’ celebrated line, "ain’t there one damn song that can make me break down and cry?" Bowie constructs the most grandiose of love songs, the most overblown, epic ballads, mouthing hollow romantic clichés as if, by saying the lines with enough simulated passion, he will actually come to feel them. And yet, of course, all of this is just a construct, too- he knows exactly what he’s doing. It’s not a cynical act, because the desire to feel remains genuine- in its way, this is as stark and troubled a record as anything from Neil Young’s contemporaneous ditch trilogy, the musical polish and role-play only thinly veiling a soul on the edge, battling with addiction and paranoia and with what he, at least, genuinely believed were dark mystical forces just waiting to drag him forever into the abyss. "It’s the nearest album to a magical treatise that I’ve written," Bowie has said, though perhaps a ritual spell of protection would be a more accurate description.

The album opens with the sound of a train. An old-fashioned steam train, chuffing from speaker to speaker and which always makes me think of Mr Norris Changes Trains by Christopher Isherwood- leaping ahead to Berlin, again – and then suddenly it isn’t a train anymore, but something far more warped and alien, and here come those flat, clip-clop piano notes, the spidery beat and Earl Slick’s strafing guitar feedback out of which a dragging, leaden riff slouches, some rough beast waiting to be born… But Bowie’s vocal is anything but rough: silken, demanding, ridiculously theatrical yet eerily convincing. ‘Station to Station’ isn’t about trains, despite being written while the notoriously aerophobic Bowie was touring America and Europe by rail; instead, it refers to the fourteen Stations of the Cross, which Bowie also equates to the eleven Sephirot of the Tree of Life in the Jewish Kabbalah- hence, "one magical movement from Keter to Malkuth," the songs most enigmatic lyric, which refers to the descent from the Crown of Creation to the Physical Kingdom, or from one end of the tree to the other.

This first section ends with a cryptic reference to Aleister Crowley’s early, poetic fusion of pornography and occultism, White Stains. A classic of decadent literature, Crowley himself later justified this short work as follows: "I invented a poet who went wrong, who began with normal innocent enthusiasms and gradually developed various vices. He ends by being stricken with disease and madness, culminating in murder. In his poems he describes his downfall, always explaining the psychology of each act." It’s not hard to imagine Bowie identifying with such a project, but before we have time to digest this, the whole song suddenly switches gear: not once, but twice, into hard, urgent funk with a proggy chord sequence, and then again, finally hitting that glorious plateau of a chorus and somehow staying there, like a never-subsiding orgasm, held impossibly aloft by Roy Bittan’s driving piano, just so long as you don’t look down- "It’s too late!" –Slick kicks in with a wired, fiery solo, and then, "it’s not the side effects of the cocaine- I’m thinking that it must be love," and we’re still up there, somehow- it’s a sustained, smooth-jagged coke high of a song, just keeping going, always up and on the one until it finally, inevitably fades out…

‘Golden Years’ is one of Bowie’s finest middle-of-the-road moments, a mainstream soul-funk ballad with mass appeal but a seriously weird core. It comes on like a love song, but what is it actually about? "Nothing’s going to touch you in these Golden Years (run for the shadows in these golden years)." It’s opaque, impenetrable, all mirrored surfaces and shifting moods. Again, the incessant, almost proto-rap delivery, listing things to do, balancing aggressive positivity ("Don’t let me hear you say life’s taking you nowhere") with brittle paranoia ("run for the shadows…") is pure coke babble, riding on the bright mellow glide of the groove and the dark empty spaces beneath… nothing’s gonna touch ya, move through the city, stay on top, all night long…”.

I am going to get to some features, where David Bowie’s studio albums are ranked. First, there are a couple of retrospectives I want to cover off. Moving to Albumism and their take on Station to Station, forty-five years after the album was released. It is my favourite David Bowie album. I have a lot of love for it. For anyone who has never heard Station to Station, do take some time to investigate it, as it is one of Bowie’s most compelling works:

“Bowie managed to fit in almost every aspect of the human condition with the first three songs on Station to Station. Side two opens with "TVC 15" featuring a Professor Longhair-styled piano riff by Roy Bittan, which plays throughout the song. For the last 45 years, I had no idea what the hell this song was about. Through an internet deep dive and a couple of Kindle purchases, I finally discovered the origins of "TVC 15." An occurrence inspired the song at Bowie's home where a hallucinating Iggy Pop believed that a TV set swallowed his girlfriend. Bowie took this incident and created "TVC 15,” where the protagonist's girlfriend crawls into a TV, and he decides to go in after her. This strange but delightful tune is a great open to side two and one of the more underappreciated songs in Bowie's catalog.

"Stay" is arguably the funkiest tune on Station to Station and could also have been on the Young Americans album. Earl Slick's guitar work is the co-star of this song, along with Bowie's vocals. "Stay" remained a staple of Bowie's live performances throughout his career.

Rounding out Station to Station is "Wild is the Wind," a hauntingly beautiful song initially recorded by Johnny Mathis in 1958 for a movie of the same title, but later flawlessly covered by Nina Simone in 1966. Bowie struck up a friendship with Simone after meeting her at a private club called Hippopotamus in 1974. As she was leaving, he called her over to his table, and they chatted and exchanged numbers. For about a month afterward, they spoke on the phone daily and talked about what it meant to be an artist who was different from everyone else. He gave her the encouragement she needed at the time, and she saw him for who he was. In her biography What Happened, Miss Simone, she is quoted as saying, "He's got more sense than anybody I've ever known," she said. "It's not human—David ain't from here." This friendship led Bowie to record "Wild is the Wind" as an homage to his friend. It is one of the most moving songs in his discography and a great end to Station to Station. Check out the incredible version he performed at the Yahoo Internet Awards in 2000.

Considering all of the personal turmoil Bowie was enduring when he recorded Station to Station, it's miraculous that this six-track album remains one of the most important and influential albums recorded in the last 50 years”.

Following David Bowie’s death in 2016, Medium argued why Station to Station matters. If some feel that it is not David Bowie’s very best album and contains few terrific songs, it is definitely one of his most important albums. A lot of people focus on David Bowie’s physical and emotion state. How he was an addict and was exhausted, yet still managed to turn in this wonderful and rich album:

“Generally speaking, Bowie had not pumped both exuberance and noirish angst into a given song before 1975. But on Station to Station, every track contains both sides of the dichotomy. The epic songs on Springsteen’s Born to Run, released mere weeks before work on Station to Station began, also encapsulated this paradox, which is possibly why Bowie poached Springsteen’s pianiste extraordinaire, Roy Bittan.

The Thin White Duke, Bowie’s new persona for Station to Station, is no Ziggy Stardust: he’s naked and comparatively defenceless. The apocalypse is not coming from without, but from within. Ziggy was Bowie — prelapsarian in reality — pretending to personify rockstar royalty in decline/sublimation, achieving rockstar royalty ‘in real life’ in the process. The Duke is Bowie — having becoming rockstar royalty — in precipitous physical and mental decline, and not hiding it very well. “Does my face show some kind of woe,” he says, not phrasing it like a question. Cracked actor indeed.

***

(Mis)communication and confusion pervade the album; even when clarity and confidence burst through, doubt is waiting in the wings. Everyone praises Bowie’s vocal on album closer ‘Wild is the Wind’, but ‘Word on a Wing’, which builds on his references to angels in ‘Golden Years’ (and to the Stations of the Cross alluded to in the title track), really is a vocal powerhouse. Ending Side 1 of the LP, it sums up the Manichean dichotomies at the album’s centre — darkness/light, rational/religious, doubt/belief — in an act of desperate faith. “A protection,” he would say of the song in later years. “Something I needed to produce from within myself to safeguard myself against some of the situations that I felt were happening.” An inelegant explanation of one of Bowie’s most elegant compositions, the statement nonetheless contextualises Bowie’s six-minute plea to be rid of the “grand illusion” (or “grand delusion”, but the effect of a fickle, faithless world is the same) that surrounds him.

Even when clarity and confidence burst through, doubt is waiting in the wings

“Does my prayer fit in with your scheme of things?” he asks God politely, seeming to eschew his own erstwhile flirtation with the Nietzschean superman idea only to claim loudly, in the song’s bridge, to be “ready to shake the scheme of things”. So — is he praying? Or is he asserting his own “scheme”? Does he even know? The song seems to end in prayer, borne out by the choral organ and the angelic backing vocals.

But Side 2 kicks off with the decidedly secular ‘TVC 15’, most of whose lyrics are indecipherable without a lyric sheet, which doesn’t matter too much when the music’s this enjoyable. It resumes the album’s key theme of communication. The music and lyrics of Station to Station probe the very concept and (f)utility of communication; c.f. Young Americans, which was simply a committed attempt at communicating volumes — about black music, about white music, about the exultations and limitations of each as well as the irrelevance of said limitations when you’re having fun — through generally impenetrable lyrics.

Ultimately, the album presents the problem of progression and momentum (hinted at by the album title, the breathless typography on the album cover, the chugging pistons on the title track that “drive like a demon”, the vast majority of the music itself) counterposed against the stasis, confusion and miscommunication explored in the lyrics. In other words, it presents the problem of life itself. ‘Stay’, the Earl Slick / Carlos Alomar showcase, again exemplifies Bowie’s frustrations with communication. “I really meant it so badly this time,” he pleads. “You can never really tell when somebody wants something you want too.”

***

Bowie appears to have achieved some sort of temporary peace in the final track, seeking refuge in another’s work, which makes sense — his own five songs have been too dense, intense and difficult to afford Bowie (and us) a breather. The song may feel at first like a misfit, but it coheres with the album: the opening lyric (“Love me love me love me love me, say you do”) suggests that the communication is as important as, if not more important than, the sentiment itself.

We are feeling, rather than just understanding, Bowie’s loneliness

The wildness of the wind (Bowie’s romance with his addressee) is something he’s wishing for, not something he has. Throughout the album, he’s seemed so alone, so uncomfortable in his own skin, that by ‘Wild is the Wind’ not only does it sound like he has no lover, it sounds like he’s never had one. The album’s tone begins to make sense, and for the first time we feel, rather than simply understanding, his loneliness. The backing vocals are no longer there. “It’s not the side effects of the cocaine | I’m thinking that it must be love”, he sang on the title track, and although the non sequitur about the “European cannon” seemed to make a nonsense of this line at the time, his audible terror that “it must be love” now slides into focus: Bowie is too far gone to be anything other than panicked at the prospect of real intimacy. Which might be why he’s hiding in someone else’s song.

“Don’t you know you’re life itself? | Like the leaf clings to the tree | Oh my darling, cling to me | For we’re like creatures of the wind | For wild is the wind”. Why do I find his delivery of this soppy line so poignant? Maybe because the whirlwind of his imagined love is a world away from the whirlwind of confusion and cocaine that’s been swirling ‘round his desolate isolation for the last 35 minutes.

“The man who knows not how to smile”

Why does any of this matter?

Partly because Bowie expressed profound loneliness without having to spell it out, which makes the album one of the most subtle, captivating pictures of loneliness (and therefore of humanity) we have.

Partly because few other albums, if any, have tackled the theme of communication (with oneself, with another, with God) so concisely, so catchily and so cathartically.

Partly because it’s worth trying to unpack why certain albums are so listenable.

Partly because the album is one of Bowie’s unmitigated successes, which makes it notable for obvious reasons.

Partly because the album doesn’t get enough press, coming between two more prominent records.

Partly because despite (or perhaps thanks to) the obfuscations, the obscure lyrics, the confusion and the chaos, the album offers a piercingly clear portrait of David Bowie circa 1976, and such a jolt of poignant clarity is how many of us are trying to plug the gap in the wake of his death.

Partly because it’s fun”.

In 2013, Rolling Stone asked its readers to choose the best David Bowie album. Rolling Stone ranked Station to Station third: “It's possible to do so much cocaine over a long period of time that you enter into a state of "cocaine psychosis," meaning you suffer from intense paranoia and memory failure. That explains why David Bowie claims to have no memory of recording Station to Station. He was doing shocking amounts of the drug, and not sleeping for days at a time. This disc was recorded largely long after midnight in a Los Angeles studio. E Street Band keyboardist Roy Bittan was sober, but most everyone else in the studio was high as a spaceship. This usually leads to horrible music, but by some miracle it produced some of the greatest songs of Bowie's career. On the epic title track Bowie even sings about the "side effects of the cocaine." It's 10 minutes and 15 seconds of absolute madness. You can almost smell the drugs when you listen to it. The disc wraps with a cover of "Wild Is the Wind," featuring some of the greatest singing of Bowie's career. This is a deeply weird album that just gets better with age”. Back in September, GQ placed it in sixth: “One of the most indelible lines in Bowie’s biography is that he had a period consuming only red and green peppers, milk and cocaine (which also coincided with a couple of pro-fascist statements). This is the album that came out of that period – and for all the havoc the drugs wreaked on his mind, his music held up. Station to Station has a bit of everything, particularly the “plastic soul” of Young Americans, with intimations of his forthcoming experimental period too. “Word on a Wing” is a shining but structurally tricksy ballad; the 10-minute title track, his longest song, is a style-shifting odyssey with a catchiness that belies the sinister, rather mystical lyrics”.

Last year, Rough Trade placed it in sixth too: “Saving your piss in the fridge so the witches don't steal it? No? Then clearly you've not huffed as much coke as 1976 Bowie while he trail-blazed through an album that simply put, he couldn't remember making. Icy funk, complex art rock and if we're being real here - his best vocal take (Wild Is The Wind) are all present and correct. Earl Slick absolutely wails throughout, his guitar textures unteachable and unreachable”. This is what Classic Rock observed last year when highlighting which David Bowie albums you should listen to: “Bowie’s herculean mid-’70s drug intake meant he claimed not to remember making Station To Station. For anyone less addled, this 1976 benchmark ranks amongst his most memorable albums. Comprising six lengthy tracks whose raw emotions hold up a mirror to Bowie’s mindset (at this point, he was trading as the problematic Thin White Duke), Station was a marked fork left from the rug-cutting soul of Young Americans, and implied the electronic leanings that the Berlin trilogy would soon explore. For instant gratification, it has to be Golden Years, but the album demands headphones and full focus”. We remember David Bowie on 10th January, ten years after he died. Instead of reflecting on that, I wanted to look ahead to 23rd January and the fiftieth anniversary of Station to Station. It is a stunning and timeless classic from…

A much missed genius.