FEATURE:

Beneath the Sleeve

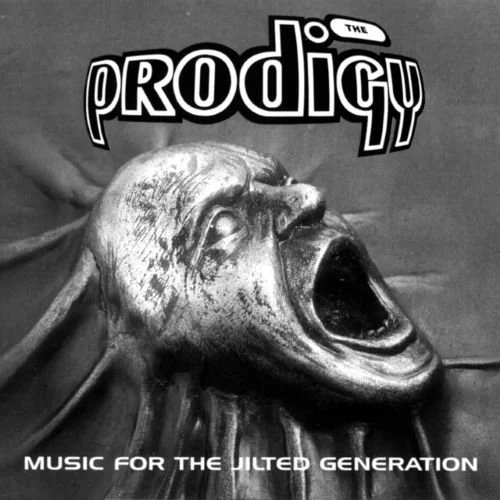

The Prodigy – Music for the Jilted Generation

__________

SOME might argue…

that there were better albums that was released in 1994. It was such a competitive and phenomenal year. However, the second studio album from The Prodigy reached number one in the U.K. and contains some of the best music from the band. I would advise people to buy the album on vinyl. I will end with a review for one of the defining albums of the '90s. I am going to start out with a few features about Music for the Jilted Generation. Thirty-one years after its release and this album is still inspiring artist and being shared. It is such an important work. I am going to start out with a CLASH feature from 2019. Marking twenty-five years of Music for the Jilted Generation, they heralded and ambitious and genre-busting classic:

“When ‘Music For The Jilted Generation’ was released in 1994, UK rave’s heyday was already waning. While hardcore splintered into clubs and subgenres, ‘Jilted’ instead revisited and re-energised the sound’s origins in hip-hop and punk rock. Producer Liam Howlett and dancer-MCs Flint and Maxim Reality promised not a return to the underground but an unholy matrimony of rave’s anarchic spirit and, well, everything and the kitchen sink.

Over 13 wildly different tracks, ‘Jilted’ swerves between the cinematic (on adrenaline-infused chase sequence ‘Speedway’) and the stadium (on rock-rave manifestos ‘Their Law’ and ‘Voodoo People’). Elsewhere, its final, three-part ‘Narcotic Suite’ finds Howlett furthest from his comfort zone, stretching rave tropes to urbane electronica (‘3 Kilos’) and sci-fi mind-benders ‘Skylined’ and ‘Claustrophobic Sting’.

End to end, the record tests the limits both of hardcore experimentalism and its original CD format – Howlett himself later regretting its 78-minute running time. Ambitious, yes. Interesting throughout, absolutely – though judge the flute solos on ‘3 Kilos’ for yourself.

Really, the power of the record shone through not on these high-minded outliers but on its string of hits – arguably the Prodigy’s finest, where Howlett’s craft reached new heights. ‘Jilted’ was packed full of hooks, even though few of them were what you’d call melodic.

Sure, there are tunes: the pitched-up vocals on ‘Break And Enter’ and ‘No Good (Start The Dance)’, the stadium-worthy shredding on ‘Their Law’. But take standout ‘Voodoo People’ for example: borrowing a two-tone riff from Nirvana’s ‘Very Ape’, it barely shifts from one note, and is the better for it. Even its anthemic synth part is more squelch and distortion than melody, as can also be said for the chainsaw-synth on ‘Poison’ – a slow motion sledgehammer blow of a record that squeezes endless musicality from a juggernaut breakbeat chassis.

It’s this weird alchemy of muted melody, texture and production tricks that stick in the brain. The magic of the Prodigy lies in these staccato, concentrated bursts of noise and energy, neatly described by Maxim’s refrain on ‘Poison’: a “pulsating rhythmical remedy”. But a remedy for what? Who jilted this generation? Sharp as edges, this album undoubtedly deepened rave’s affinity to anti-authoritarian punk”.

I am going to move to a feature from VICE. Writing in 2014, they marked twenty years of The Prodigy’s Music for the Jilted Generation. I remember when it came out in 1994. Launched at a time when music was arguably at its peak, it was like nothing I had heard before. Even now, the album takes me aback (in a good way). Maybe it is not as deep an album as many that was released at that time. However, it brought people together and captured imaginations. A unifying and startling brilliant album, we will be dissection and celebrating it for many years more:

“This is the world that Music for the Jilted Generation was precision-tooled to soundtrack. The Prodigy had already come punching and kicking into the dance world, both perfecting and satirising the sound of hardcore, “killing rave” (as an early Mixmag cover story had it), proving that performance and bolshey personality still had their place among the faceless DJs, and delivering an absolutely shit-hot album in The Prodigy Experience. But Music for the Jilted Generation was the perfect divestment of any last fucks given, a willfully uncool thrash-about that didn’t rely on allegiance to any of the micro-scenes now proliferating, but somehow provided some weird sort of negative unity across the whole proverbial generation; perfectly expressing the skunk-paranoia, vodka-swilling, bad-E’s collective “UGGGGHHH” that came after all the “Woo yeah, c’mon, let’s go!” of rave’s peak years.

They weren’t the first act to realise that to expand they’d need to break out of the scenes and habits of the dance world – bands like The Orb, Orbital, Fluke, The Shamen and even Aphex Twin were taking it to the arenas with big son-et-lumiere shows – but The Prodigy were the ones who really went at it like a big, bastard rock band. By bringing Pop Will Eat Itself (one of the few bands who’d really honed rock/dance crossover) on board for ‘Their Law’ they gave themselves a leg-up, but probably Liam Howlett could have set mosh pits churning anyway.

Early tracks like ‘Charley’ and ‘Everybody in the Place’ showed the first glimmers of an instinctive understanding of The Big Riff that was not about the hypnosis of techno, or even the hyper-stimulation of hardcore, but about dragging the music back into the fist-pumping, chant-along experience of rock music. For better or worse, they and their shows preempted everything that is big and brassy in 21st century EDM. Every new superstar DJ with huge LED shows, massive riffs and vertiginous drops, and most of all Skrillex, owes them a very substantial debt.

Just like a lot of new EDM, Music for the Jilted Generation is basically very ugly. The pop-hardcore of The Prodigy Experience is still there: teeth gritted as tightly as ever, rock riffs expressing hard guitar music as full fat cheese, heading back towards the trash of Mötley Crüe and co. that grunge self-righteously decided to save us from, and the electronic elements all reach for the shiniest, most instant rush effects. If you listen now to ‘Start the Dance (No Good)’ you’ll hear how, for all its hardcore tempo and breakbeats, it sits as close to Faithless and Felix ‘Don’t you Want Me’ as anything you could describe as underground. Everything is on the surface. There’s nothing subtle from beginning to end – and that includes the disaffection that it expresses, which for all the pontificating about injustice of ‘Their Law’ is nothing more than that aforementioned “UGGGGGHHH” than any more sophisticated articulation of what it was to be alive in 1994.

All of which is precisely why it works. Nobody wanted political analysis or fine detail from Liam and his gang of dark clowns. We wanted to mosh. We wanted a racket that drowned out our tinnitus and picked us up in the same way that a bag of cheap speed did. And for all its negativity and steam-hammer unsubtelty, Music for the Jilted Generation created good times. The first time I ever saw The Prodigy live at a festival, I was in a bad mood. Darkly stoned and paranoid, I surrounded by a right old mix of people but notably a large contingent of football hooligans, banging back the lager, coke and GHB”.

Before getting to a review, I am going to get to a feature from Kerrang!. Writing in 2019, it is a brilliant feature that I would advise people to read in full. An album that you will definitely want to grab on vinyl, I wanted to go beneath the sleeve, as it were, an get the background and detail about one of the seminal albums of the 1990s. Music for the Jilted Generation is a work of genius:

“Rock music, you see, was pretty damn healthy in 1994, but it was evolving, as it always has. Around the mid-’80s the barriers between punk and metal came down, and thrash was born. Crossover, whatever the hell you want to call it. Two tribes that had previously been enemies in a very literal sense had come together, and by the ’90s more barriers were falling. The unthinkable was becoming, well, thinkable. This is especially true of the Judgment Night soundtrack of 1993, which saw such improbable collaborations as Slayer and Ice-T, Biohazard and Onyx, Faith No More and Boo-Ya T.R.I.B.E, Pearl Jam and Cypress Hill, metal and hip-hop colliding in the most unlikely ways, to result in something that was undeniably brilliant. Opening doors that were impossible to close again.

And then there was the dance/techno scene waaay off over there in a field of its own, perhaps best summed up by the cartoon in Viz magazine of Ravey Davey dancing around a car alarm. Granted, the field in which they resided was the cause of national headlines and moral outrage due to illegal raves, which ultimately led to the so-called Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994, a knee-jerk reaction that prohibited such gatherings, restricting – among other things – the right to freedom of assembly, with bizarre references to 'repetitive beats'. But while this was a concern to any right-minded rock fan, the music was not.

The Prodigy, meanwhile, were massive on the dance scene. Their 1992 debut album Experience is considered a classic of the genre, but songwriter Liam Howlett, having conquered that scene, was growing bored with it and looking for fresh challenges. Due to the eclectic nature of European festivals, they had shared stages with the likes of Rage Against The Machine, Suicidal Tendencies, and Biohazard, and they wanted some of that energy. As MC Maxim Reality put it, “We're used to parties where kids get carried over the barrier now and again, but suddenly there's a sea of people jumping around and stage diving! It was unbelievable!”

So began the change to a heavier sound, Liam sampling rock guitars and recruiting guitarist Jim Davies, a Pantera fanatic who would beef up the live sound on tracks like Voodoo People and Their Law. But still the rock world was clueless. Maybe a handful of rock fans – literally a handful – were aware that something cool was going on, but to the rest The Prodigy were assumed to be little more than a joke, if we're completely honest.

That The Prodigy somehow ended up being championed by Kerrang! was almost entirely accidental. In June ’95, a full year after the release of Jilted Generation, I went to Glastonbury festival pretty much on a whim. It was hot and sunny that year. Skunk Anansie and the Black Crowes were playing... it seemed like a good idea at the time. By Friday night, having imbibed a few substances, my friends and I were in party mode. A couple of them wanted to check out The Prodigy and I didn't want to watch Oasis, so I went along with them. What I witnessed for the next hour was utterly mind-blowing!

“Who came here to rock?” demanded Maxim. Well, 'I did,' I thought, 'But it's not going to happen with you lot.' Oh, how little I knew. And then this punk rock nutter, later known to all of us as the late and very great Keith Flint, came charging across the stage in a hamster ball, the band kicked into Break And Enter, and the place went fucking nuts! By Monday morning I was demanding that we put them in Kerrang!.

In hindsight, The Prodigy were still very much a dance band, yet to make the full transition to rock, and Jilted Generation is a dance album, albeit a very good one, with just a couple of rock tracks. It's no wonder we got death threats for covering them. But, also in hindsight, there are elements here that are not too far from the trance vibe of Hawkwind, and, in some ways, it was inevitable that the energy of dance music would eventually seep into the rock scene. Killing Joke had flirted with dance beats on the Pandemonium album of ’94 and they were not alone. The big difference was that The Prodigy had the audacity to do it the other way around and to do so entirely on their own terms.

“I don't look at the music as techno, anyway,” said Liam at the time. “It's Prodigy music, ’cause we don't limit ourselves.”

Music For the Jilted Generation is still groundbreaking, and The Prodigy remain one of a kind”.

I will end with a review from the BBC. There are some many positive reviews for Music for the Jilted Generation. I don’t know if I have done it justice, but I would once again encourage anyone reading to go and listen to the album. Own it if you can. There are other great features like this that give more detail and insight into the album. In 2003, David Bowie named it (the album) among his favourite music from the 1990s. Music for the Jilted Generation has been voted among the best albums ever by several publications:

“It was their chart-topping 1996 single, “Firestarter”, that first took up lighter and aerosol and burnt the name of The Prodigy – and the piercing-covered gurn of Keith Flint – onto the national consciousness. But if you want to mark the point this gang of Essex ravers first learnt to unite the chemical rush of acid house and the anti-authority attitude that had hitherto been the preserve of black-clad anarcho-punks like Crass and their ilk, not loved-up glowstick twirlers, look back a couple of years to their 1994 album Music For The Jilted Generation.

Recorded against the backdrop of the Criminal Justice Act, the ’94 legislation that effectively criminalised outdoor raving – ‘How can the government stop young people from having a good time?’, reads a note on the inner sleeve –Music… simmers with righteous, adrenalised anger, rave pianos and pounding hardcore breakbeats augmented by gnarly punk guitar, wailing sirens and on “Break And Enter”, the sound of shattering glass. At no point is this merely a band coasting on edgy vibes and bad attitude, though; rather, this is a record that saw Prodigy mainman Liam Howlett maturing as a producer, increasing his palette of sounds and instruments without diluting The Prodigy’s insolent rush, and simultaneously smash ’n’ grabbing from a diverse range of influences that would be neatly integrated into the band’s design.

On “Their Law”, a guesting Pop Will Eat Itself supply a vitriolic vocal aimed at the powers that be. The knuckle-scraping guitar riff from Nirvana’s “Very Ape” forms the scuzzy chassis to the flute-augmented ‘Voodoo People’. And “No Good (Start The Dance)”, with its Kelly Charles vocal hook, proves that despite The Prodigy’s punk snarl, their pop impulse remained intact.

Best track here, though, is the immortal call-and-response track “Poison”, marking MC Maxim Reality’s on the microphone. And in a surprising nod to the emerging phenomenon of the chill-out room, Howlett divides the album’s final three tracks off into “The Narcotic Suite”, a spacey, synthesiser-powered closing stretch that closes the album like a valium comedown. Anyone who called The Prodigy a one-trick pony clearly never heard this”.

I am not sure which album I am going to focus on for the next Beneath the Sleeve. It will be very different to Music for the Jilted Generation! An album that came out when I was eleven and definitely made an impression on me, a whole new generation are discovering it. When it comes to this 1994 sonic explosion and revolution, there are few other albums…

THAT equal it.