FEATURE:

Kate Bush: The Tour of Life

Controversy Around The Dreaming’s Eponymous Single

__________

FOR most of Kate Bush’s singles…

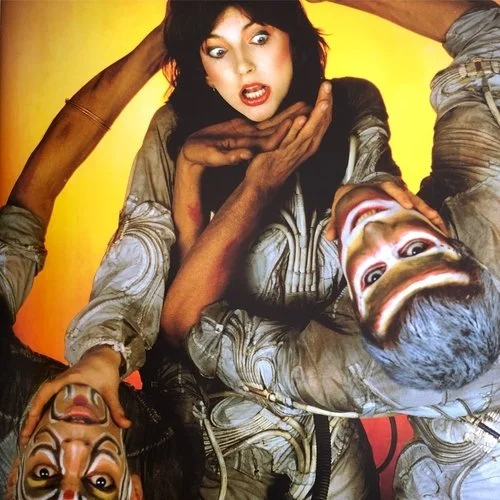

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush in 1982/PHOTO CREDIT: Guido Harari

I write anniversary features every year. It is a way of exploring the songs in more detail and bringing them to people who may not be aware of them. The Dreaming’s eponymous track was released as a single on 26th July, 1982. It was the second single from The Dreaming. Sat in Your Lap was released in 1981. Maybe not an obvious single choice, it reached forty-eight in the U.K. Maybe a hard sell for a single, it is not the most commercial-sounding song. The Dreaming as a whole was not really designed with radio-friendly songs in mind. However, there is a bit to discuss about The Dreaming forty-three years after it was released. Before coming to some of the issues with the song, it is worth saying that Bush’s heart was definitely in the right place. Someone always concerned about people and how they were treated, for her to discuss the treatment of the Aboriginal homelands by white Australians in their quest for weapons-grade uranium is nothing forced or insincere. The Dreaming is an album where Bush talks about issues like war and destruction. The quest for knowledge. There are some big themes addressed. However, when it comes to talking about The Dreaming as a single, I guess we need to look at it from different sides. Before getting to that, here is some interview archive from the Kate Bush Encyclopedia:

“We started with the drums, working to a basic Linn drum machine pattern, making them sound as tribal and deep as possible. This song had to try and convey the wide open bush, the Aborigines – it had to roll around in mud and dirt, try to become a part of the earth. “Earthy” was the word used most to explain the sounds. There was a flood of imagery sitting waiting to be painted into the song. The Aborigines move away as the digging machines move in, mining for ore and plutonium. Their sacred grounds are destroyed and their beliefs in Dreamtime grow blurred through the influence of civilization and alcohol. Beautiful people from a most ancient race are found lying in the roads and gutters. Thank God the young Australians can see what’s happening.

The piano plays sparse chords, just to mark every few bars and the chord changes. With the help of one of Nick Launay’s magic sounds, the piano became wide and deep, effected to the point of becoming voices in a choir. The wide open space is painted on the tape, and it’s time to paint the sound that connects the humans to the earth, the dijeridu. The dijeridu took the place of the bass guitar and formed a constant drone, a hypnotic sound that seems to travel in circles.

None of us had met Rolf (Harris) before and we were very excited at the idea of working with him. He arrived with his daughter, a friend and an armful of dijeridus. He is a very warm man, full of smiles and interesting stories. I explained the subject matter of the song and we sat down and listened to the basic track a couple of times to get the feel. He picked up a dijeridu, placing one end of it right next to my ear and the other at his lips, and began to play.

I’ve never experienced a sound quite like it before. It was like a swarm of tiny velvet bees circling down the shaft of the dijeridu and dancing around in my ear. It made me laugh, but there was something very strange about it, something of an age a long, long time ago.

Women are never supposed to play a dijeridu, according to Aboriginal laws; in fact there is a dijeridu used for special ceremonies, and if this was ever looked upon by a woman before the ceremony could take place, she was taken away and killed, so it’s not surprising that the laws were rarely disobeyed. After the ceremony, the instrument became worthless, its purpose over.

I suppose the association with Rolf Harris is an unfortunate one. He played on the song and would later feature on Kate Bush’s 2005 album, Aerial. Luckily, that album was reissued on streaming services and Harris was replaced by Bush’s son, Bertie. The vinyl has been reissued too so, if you have an original 2005 copy, I would suggest replacing it. It is commendable that Bush, like she always did and always would, was embracing other cultures and sounds. Some of the issues and controversy about The Dreaming stemmed from its original title, The Abo Song, which used a racial slur. Promotional copies of the single were circulated with this title before being recalled due to the offensive language. The song has also been slammed for potential cultural appropriation, specifically concerning the use of the didgeridoo and Aboriginal imagery. Bush did want to highlight the plight of Aboriginal Australians and the destruction of their land. However, to many, Bush’s portrayal, even with good intentions at heart, perpetuated a colonial narrative. There is this accusation of cultural appropriation. Whilst Bush was voicing her horror at what Aboriginal people have faced and how their land was being destroyed, the fact that she was a white artist did lead to people to question her motives and authenticity. Did this do more harm than good? Bush using the language and words of colonisers has given The Dreaming an awkward and complicated legacy. There are positives to focus on. The use of a didgeridoo in a British single in 1982 would have been radical. Bush was always incorporating instruments from different parts of the world in her albums. This was Bush using an instrument she came across whilst vacationing in Australia.

I do want to come to a review of The Dreaming from Medium. It is clear that The Dreaming is not necessarily one of her most loved singles. It was a low chart position. After a run of successful singles from 1978 to 1981’s Sat in Your Lap, The Dreaming charting outside of the top forty was a blow. It was a trend that continued until Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God) was released in 1985. However, it is an interesting song that I feel is underrated as a piece of work:

“The album’s namesake and second single opens up the second half, side B, of the album. We are introduced to a didgeridoo and heavy engulfing drumbeat. After a sudden BANG! Kate starts to sing in a prominent Australian accent. The production is wide and open, yet heavy and dark, like a thunderstorm approaching a wide dry plain. Approaching the pre-chorus, Kate breathes quickly (hoo-hoo-hoo-ha-ha-ha) using breath as a rhythmic element, something we’ll hear later on in “All The Love.” It’s remarkably similar to the breakdown in Depeche Mode’s “Personal Jesus” as well (though I can’t say whether or not Kate directly inspired it!)

The chorus opens to a group of people sing-spelling “D-R-E-A-M-T-I-M-E” while Percy Edwards impersonates a goat and a synthesized whistle plays in the background. The song is sonically arresting throughout and remains to be a feat in production. It maintains intensity and atmosphere. It is metallic and natural. To achieve the metallic tone of the main melody, Kate plugged a guitar and piano into a harmonizer that were fed into a reverb plate as well that fed the rising octave back into the harmonizer — an effect used several times on the album. The “bang” in the lyrics is a combination of the recorded sound of a car door closing and a synth tone.

Some of my favorite moments on the album are when the crowd come in to sing “You’ll find them in the road!” and proceed to cheer and slowly fade out in a wash of reverberated white noise, bringing the song down like a setting sun.

Lyrically, Kate touches upon the plight of the Aborigines being run out of their sacred land as colonizers come in to dig for ore — easily summarized in these lyrics “Erase the race that claim the place and say we dig for ore/(See the light ram through the gaps in the land)/Dangle devils in a bottle and push them from the Pull of the Bush.” She humanizes the native Aborigines, and attempts to show the gentrification from their eyes. It should also be noted that Kate wrote remarkably similar lines of poetry when she was young:

“The blood red sun sinks into the skull of a dead man.” — From The Crucifixion, written when Kate was only 11 or 12”.

I did want to mark forty-there years of The Dreaming. It’s eponymous single was definitely important. Two singles from Never for Ever, Breathing and Army Dreamers, were more political in nature. The Dreaming is too. The next single released from the album, There Goes a Tenner, arrived in November 1982. Much jauntier in its tone, it was an even bigger commercial disappointment in the U.K. It did not chart at all! I do applaud Kate Bush for releasing music which was less commercial than EMI hoped. She was making the music she wanted to and tackling themes that were beyond that of love and the personal. The Dreaming is significant as it is a song where Bush shines a light on a people who were witnessing this devastation and colonisation. I can see why she felt angered and what to do something. However, I do wonder whether the decision to play an Australian coloniser was the best move. It makes the song sound quite dated. One you will not hear played on the radio too much. Also, the fact Rolf Harris’s part has not been removed – I guess as it is integral to the song – gives it a black mark. A song that was performed live a few times, there is sort of this bittersweet aspect. However, we need to focus on the positives as well as the negatives. It is a powerful track that has this unusual and untraditional sound. Listen to The Dreaming as an album and you can hear this invention and variation through all ten tracks. It is a stunning album that everyone needs to hear. Its title track is great in so many ways but, unfortunately, when it comes to its politics and the issues around cultural appropriation, then it…

MISSES the mark.