FEATURE:

Beneath the Sleeve

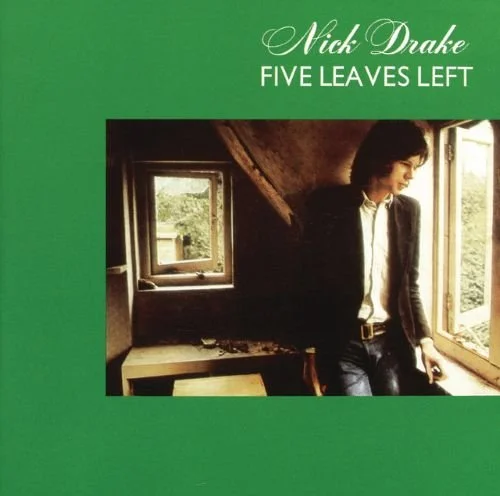

Nick Drake - Five Leaves Left

__________

BEFORE discussing…

IN THIS PHOTO: Nick Drake in 1969/PHOTO CREDIT: Keith Morris

the album and giving a bit more detail about its brilliance and legacy, it is worth noting that there is an expansion on Five Leaves Left. Nick Drake’s debut studio album was originally released on 3rd July, 1969. It has recently had this reissued and expanded edition. The making of edition gives us demos, alternative versions and outtakes. Giving us greater insight into this classic album. One that still sounds remarkably engrossing and beautiful fifty-six years after its release. This feature gives more details about Nick Drake’s 1969 debut:

“Between 1969 and 1972, Nick Drake recorded three stunning studio albums of detached yet vivid Blake-ian lyricism ripe with images of the elements and an autumnal brand of chamber folk rolling behind his handsomely burnished baritone. If you can imagine David Sylvian, only sadder and still somehow more alive, you can picture Drake’s glass-spun wonder and doomed romanticism. Produced by legendary aficionado of all things rural Joe Boyd and featuring Fairport Conventioneer Richard Thompson along with a small string section, Five Leaves Left was Drakes’s first album, one filled to the brim with his delicate and bluesy bounty, yet somehow leaving the listener with something incomplete about the process. Where did he come from and how did he find his way to the UK’s king of all things dulcet and rustic, Boyd? Why was this guy so moody and sullen? Could he, perhaps, speak up a bit?

To answer these questions, Island/UMe has just released a dissection of the debut across four vinyl albums—a collection that starts not with the singer-guitarist’s 4-track demo recorded in his college dorm room in January 1968, but rather mere months later when Boyd got wowed by the composer-vocalist and pushed him immediately into Sound Techniques studio that March. Meant to tell a story of Five Leaves Left’s construction, each demo, outtake, and previously unheard version on The Making Of radiates the piecemeal feel of a novice grasping his way through a new endeavor (didn’t all of Drake’s music sound randomly unvarnished despite their ornate orchestration?) and one’s personally burgeoning art form. That this box’s final disc is the original album—lustrously remastered, but not over-mastered, by its original engineer, John Wood—gives the new collection a sense of history to go with its mystery.

Not that its third album of sessions toward the end of 1968 isn’t musically valuable, lending new ears to the fresh, previously unrecorded “River Man” as it does—but it’s albums one and two of The Making Of that show off, in great detail, how something so unassuming got assumed. Here, the never-before-heard tapes of Drake’s Cambridge buddy Paul de Rivaz and fellow student and string arranger Robert Kirby from October 1968 unfurl with Drake doing his assuredly skeletal thing on warm, weird moments such as “Blossom” and “Made to Love Magic” while preparing for an upcoming live performance. The intimacy and unhampered realness of “Day Is Done” and “Time Has Told Me” are weighed starkly against Drake’s surprisingly talky bits of conversation where he’s very clear on what he wants: sounds that should be “as expansive as possible” and “celestial.” Lest anyone think that Nick Drake wasn’t career-minded, stop here. “I’m afraid this is proving to be an unprofessional tape altogether partly due to intoxication,” he says, quietly, before moving into a spirited take on “Mickey’s Tune.”

Album one is the logical starting point for this box—one where you hear Boyd in March of 1968 announcing, “OK, here we go, whatever it is, take one,” before Drake leapt into the small, pretty storm of “Mayfair,” run roughshod into “Time Has Told Me.” Oddly enough, Drake’s spare, rustic takes of “Fruit Tree,” “Man in a Shed,” and “Saturday Sun” are the same three songs that close out the windswept, fall-weather luster of Five Leaves Left and its silvery sophistication in its finished version. Not only is this box set a gorgeous addition to the recent dissection of Nick Drake’s valued work, it’s also a schematic on how his other two studio albums should tell their stories in full”.

I will explore this new box-set very soon. It is not only important for existing Nick Drake fans. The Making of Five Leaves Left is a perfect introduction for new listeners. Those who might not know anything about Nick Drake. In 2019, The Student Playlist provided a detailed and interesting examination of Five Leaves Left and Nick Drake’s career. There are some sections from the feature that I want to use here, but do go and read the whole thing:

“A keen student of literature, having read English Literature at Cambridge University, Drake’s lyrics are evocative yet cryptic enough to withstand almost endless analysis. Inspired chiefly by a childhood of English Romantic poets, the likes of Blake, Yeats and Vaughan in particular, the lyrical and musical themes on his 1969 debut album Five Leaves Left are instantly timeless and transportive. Fascination with human behaviour and interaction is one core theme, but his observations haven’t yet been steeped in the hopeless alienation that would characterise Drake’s later work.

Quite aside from the breathtaking and consistently excellent quality of Drake’s songwriting at the age of just 20, on top of Joe Boyd’s generous production and the virtuoso musicianship from the aforementioned Thompsons as his backing, what’s most striking about Five Leaves Left is how clear and visionary it is. Although every single note is almost obsessively arranged and rehearsed, it never feels like a museum piece – instead, it’s a living, breathing musical document, as relevant today as it was back then, and one that just as accurately reflects the late Sixties as Sgt. Pepper’s or Tommy. Instead of the sunshine and love of the California hippy vision, Five Leaves Left was something more debonair and English. Although Boyd’s production was warm, Drake’s songs and delivery were pastoral and melancholic, like the cool shade of a tree on a blazing summer afternoon. His carefully picked and strummed acoustic guitar rings out with crystalline beauty, tying together the album’s (slightly) more upbeat moments with its baleful ones.

The clean, stern string arrangements on the stunning ‘Way To Blue’, its bittersweet atmosphere underscored by the shifting minor-major key shifts, were the result of Nick Drake’s insistence on getting his schoolfriend Robert Kirby to score the strings for it, against the advice of Boyd and the label. It’s minor, but it does show that Nick Drake wasn’t always an introverted, self-questioning soul, and in artistic terms was capable of getting his vision across with assurance.

“So I’ll leave the ways that are making me be / What I really don’t want to be,” he sings in his floaty, peculiarly English baritone on the lush opening track ‘Time Has Told Me’, a gorgeous moment that speaks to a quiet optimism, a mood that ended up being all too rare in Drake’s writing. The fantasia of ‘The Thoughts Of Mary Jane’, with its (incredibly) uncredited flute-playing adorning a wistful melody. and evaporates like a daydream. The spectral ‘Fruit Tree’ could almost pass for a McCartney-esque rumination on existence (“Life is but a memory / Happened long ago / Theatre full of sadness / For a long forgotten show”), and the galloping piano of ‘Man In A Shed’ chases Drake’s guitar around the mix in an upbeat moment that breaks the pace.

These moments are all brilliantly reflective of the British folk scene at the time, but Five Leaves Left also drifts in to darker and less musically conventional territory for the genre. Take the weary, questioning lyrics of ‘River Man’, for instance, Drake making allusions to concepts about actions and consequences. That mood is ruminative and mysterious, but tracks like the bare-boned ‘Day Is Done’ are much starker, reading like a heartbreaking essay on negativity and the futility of effort (“When the game’s been fought / You sped the ball across the court / Lost much sooner than you would have thought”). On the beguiling ‘Three Hours’ and the hidden gem of ‘Cello Song’, Drake and his musicians explore quasi-Eastern sounds that pitch his music halfway between folk and psychedelia.

Although it failed to register any kind of commercial impact, Drake’s backers at Island felt it logical to carry on in the same vein as Five Leaves Left. He and Boyd went all-out for his second album Bryter Layter, released in 1971 and festooned with a much more generous backing of organs, bass guitars, and choir and strings in places”.

I have heard some recent interviews where Gabrielle Drake, Nick’s sister, talks about Five Leaves Left and her brother. I am going to move to a feature from Rolling Stone about The Making of Five Leaves Left. I think we learn more about Nick Drake as a songwriter with these outtakes and demos. This peerless talent working out these songs that have endured for decades and inspired so many other artists:

“Sound Technique’s control room overlooked the recording floor, and Boyd often sat there while Wood and Drake worked below. The engineer spent a lot of time with Drake, even sometimes driving the songwriter back to Cambridge on his own way home to Suffolk. “I always had a very easy relationship with Nick, and we’d talk about anything,” Wood says. “He had a sense of humor. He wasn’t dour at all, but he was quiet.”

You can get a sense of Drake’s personality on the second tape, cut on a Grundig reel-to-reel recorder in the fall of 1968 by fellow Cambridge student Paul de Rivaz, whom Drake met the previous year. “I will never forget his rendition of ‘House of the Rising Sun,’” de Rivaz tells Rolling Stone. “The guitar riff at the beginning was absolutely made for him.”

Drake was working with arranger Robert Kirby, who was also attending Cambridge at the time. It’s fascinating and intimate, as though you’re sitting in the room with these university students. Fans will likely lose their minds here as they hear Drake actually speaking before each track, appearing chatty and joyful, a stark contrast to how the public perceives him. “As you can tell from some of the comments in the tape, he was jolly about a number of things, and quite jokey,” says de Rivaz. “I’m so glad we can reveal the true Nick,” adds Gabrielle.

Before the crisp, delightful “Mickey’s Tune” — completely unheard until now — Drake admits the tape is proving to be “unprofessional,” and jokes that he’s intoxicated, though de Rivaz says he was probably just hungover. (When I mention this moment to Wood, he said, “Nick certainly smoked weed, but he never, ever worked when he was anything other than absolutely stone-cold sober.”)

The direction that Drake gives Kirby on the tape — possibly some flute here, a string quartet there — demonstrates that even before his debut was recorded, Drake knew how he wanted his music to sound. (The liner notes reveal he was a fan of the Beach Boys’ 1966 classic Pet Sounds.) “At that very young age, he knew exactly what he wanted, and this recording showed it,” Gabrielle says. This proved to be especially true when musician Richard Hewson first contributed arrangements to the album, and an unsatisfied Drake used Kirby instead. “I think it’s a bit of a sore subject, to be honest,” Storey says of Hewson’s early involvement.

De Rivaz ended up keeping the tape, and never forgot about it in the ensuing decades. “I knew it was worth keeping,” he says. “I thought, ‘Well, a little bit of history, I’ll keep it.’” Though de Rivaz traveled the world for his job with British Petroleum, he kept the tape safe in his London home, refusing to fly abroad with it in fear of magnetic scanners at airports. A lifelong horse rider, he connected with Chandler in April 2017 through his fellow polo player Kenney Jones (drummer for the Faces and the Who). “I was sitting at home,” de Rivaz remembers. “The phone rang, and somebody said, ‘Hello, I’m Johnny Chandler from Island Records, and I think you might have an interesting tape.'”

De Rivaz then met with Callomon and Gabrielle at Abbey Road. “I duly appeared and said, ‘This is the tape, which you’re not going to play, and this is the CD, which has a copy of what’s on it,’” he said. “When it finished, there was this sort of silence, and poor Gabrielle was physically a bit upset, hearing her brother after so many years.”

Asked about this moment, Gabrielle tells Rolling Stone, “It was a sudden light thrown onto the Nick of my youth and his — a Nick too often hidden behind the cloud of his final sad years”.

I am going to end with a review for The Making of Five Leaves Left. However, it is worth thinking about the legacy of the album. Even though it was not really a commercial success, that does not really matter. The fact that we are still talking about the album and it has been so talked about. That is much more important than sales. Classic Album Sundays wrote about how Five Leaves Left sold low. However, it went on to inspire other musicians and now is this timeless album:

“Although Boyd was sure that Drake’s first album would follow in the footsteps of Leonard Cohen’s debut that sold 100,000 copies despite the singer/songwriters refusal to tour, the response to the release of ‘Five Leaves Left’ was underwhelming. The only British radio DJ to give the album airtime was John Peel but even this behemoth’s support did little to spark sales which totalled about 6,000 (a lot by today’s standard’s but depressing by those of the late sixties).

However, with time yet sadly decades after Drake’s early death, ‘Five Leaves Left’ and Drake’s following two albums ‘Bryter Layter’ and ‘Pink Moon’ have grown in popularity inspiring musicians such as R.E.M.’s Peter Buck, Dream Academy (who penned a song in tribute to the late musician) and Paul Weller (who helped champion Drake’s music), amongst countless others. Perhaps the fact that Drake did not neatly fit into a popular sound and genre at the time of his debut’s release in 1969 prompted his posthumous cult status as ‘Five Leaves Left’ does not sound like a reflection of the times but in effect, timeless”.

I will end with a review from The Line of Best Fit for The Making of Five Leaves Left. You can buy that album here, though you can obviously stick with the original. It is a gorgeous and rich album that I first heard when I was a teenager and I have loved it ever since. Even though I have not revealed much about the making of the album, I hope I have taken you a little deeper into Five Leaves Left and its brilliance:

“Earlier issuings of material not included on the original three albums have necessarily been rather fragmentary in nature, and although it is good to have both Time of No Reply that has unreleased songs, in addition to more familiar ones in different arrangements, from the years 1968 and 1974, and Made to Love Magic that similarly provides unreleased recordings from those years, this new issue is, in so many respects, by far the finest of all, including so much in an appropriately-presented way that allows a remarkable insight into the work and the decision-making behind that first record within the more concentrated 1968-69 timeframe.

For instance, the de Rivaz-tape version of “Made to Love Magic” is beautiful and, wonderfully, has Nick carefully explaining how a flute would accompany his guitar at certain points. The version orchestrated by Richard Hewson and included on Time of No Reply, though manifestly better recorded, seems a little over-lush, lacking the elemental quality of the college room rendering. On the Made to Love Magic album, a composite version, simply called “Magic” (from Sound Techniques [1968] and Landsdowne Studios [2003]) that has some creative orchestration and re-mixing by Robert Kirby and John Wood, is undoubtedly better than Hewson’s, not least because it has the flute part prominent, but it has not the extraordinary combination of delicacy and starkness that makes the student account so compelling.

The choice and sequencing of material from various dates and sessions show both intelligence and sensitivity. Of course, as the Preface, written by Cally Callomon (who, with Gabrielle Drake, manages Nick’s Estate) in the accompanying book acknowledges, some would like to have everything on the record, as it were. However, what is presented has been judiciously selected and respectful of the artist, and shows both development and, in places, roads that could have been, but were not, taken. A fine illustration is provided by a comparison of “Strange Face” from the Beverley Martyn reel (a spare rendition, with just vocal and guitar) with the rough mix of a very different version (vocal, guitar, congas, shaker and various other unspecified instruments) from six months on; the composition later became “Cello Song”. Similarly, the accounts of “Day Is Done” include some imaginative instructive reconstruction to highlight the thought processes over the period April ‘68 / November ‘68 / April ‘69.

Neil Storey’s extensive research in locating all surviving tapes and takes is worthy of the highest praise. The physical quality of the book is uniformly excellent (textured covers and thick glossy pages, with finely reproduced images), and the extensive essay covering the recording processes is especially good on the discussions concerning the arrangements, with valuable detailed recollections from Joe Boyd and double bassist Danny Thompson, as well as from Robert Kirby, a music student friend who not only recorded Nick doing an exquisite one-off piano and vocal version of “Way To Blue” in Cambridge, but also carefully worked out some fine orchestration features: “He’s done a rather beautiful string quartet arrangement for “Day Is Done” … Naturally, it’s rather a lengthy process” noted one letter home.

The narrative of Five Leaves Left is long and complex. Now that it has been told, in words and music, the record’s greatness is surely only enhanced. This release is the culmination of a remarkable project for which we should all be grateful to Gabrielle Drake and the archival team”.

One of the all-time best debut albums, Nick Drake’s Five Leaves Left should be heard by everyone. I would recommend it to everyone. Despite the fact Nick Drake’s recording career was quite short, his influence is huge. His songwriting genius clear. His 1969 debut is sublime. If you have not heard Five Leaves Left yet, then make sure you do. It is a listening experience…

YOU will not forget.