FEATURE:

John Lennon at Eighty-Five

Double Fantasy: The Final Chapter

__________

THERE have been posthumous releases…

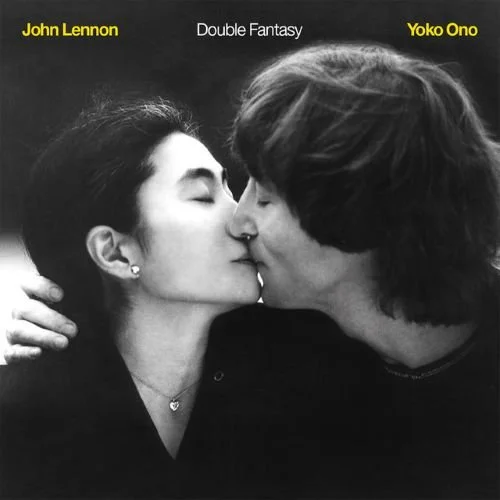

IN THIS PHOTO: John Lennon and Yoko Ono at the Hit Factory in Manhattan on 7th August, 1980, the first day of recording for Double Fantasy/PHOTO CREDIT: Roger Farrington

but, just a month before John Lennon as murdered in December 1980, Double Fantasy was released. A John Lennon and Yoko Ono album, I think there was a feeling that, five years after the underwhelming Rock ‘n’ Roll, a new John Lennon album would be just him. Even though it is not as esteemed and highly regarded as John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band (1970) and Imagine (1971), I think that Double Fantasy is hugely important. Seeing as it was John Lennon’s only album of the 1980s. Where he was heading creatively. His eighty-fifth birthday is on 9th October. My second feature to mark that is about an album that divides people. I think it includes some of his best solo tracks. Including Mother, Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy), (Just Like) Starting Over and Watching the Wheels. I want to start out by highlighting some sections of Rolling Stone’s January 1981 edition. The month before (just days before John Lennon’s death), they published this incredible interview. Jonathan Colt spoke with Lennon about his art and the new album, Double Fantasy:

"In 'Beautiful Boys,'" I add, "Yoko sings: 'Please never be afraid to cry... / Don't ever be afraid to fly... / Don't be afraid to be afraid.' "

"Yes, it's beautiful. I'm often afraid, and I'm not afraid to be afraid, though it's always scary. But it's more painful to try not to be yourself. People spend a lot of time trying to be somebody else, and I think it leads to terrible diseases. Maybe you get cancer or something. A lot of tough guys die of cancer, have you noticed? Wayne, McQueen. I think it has something to do -- I don't know, I'm not an expert -- with constantly living or getting trapped in an image or an illusion of themselves, suppressing some part of themselves, whether it's the feminine side or the fearful side.

"I'm well aware of that, because I come from the macho school of pretense. I was never really a street kid or a tough guy. I used to dress like a Teddy boy and identify with Marlon Brando and Elvis Presley, but I was never really in any street fights or down-home gangs. I was just a suburban kid, imitating the rockers. But it was a big part of one's life to look tough. I spent the whole of my childhood with shoulders up around the top of me head and me glasses off because glasses were sissy, and walking in complete fear, but with the toughest-looking little face you've ever seen. I'd get into trouble just because of the way I looked; I wanted to be this tough James Dean all the time. It took a lot of wrestling to stop doing that. I still fall into it when I get insecure. I still drop into that I'm-a-street-kid stance, but I have to keep remembering that I never really was one."

"Carl Jung once suggested that people are made up of a thinking side, a feeling side, an intuitive side and a sensual side," I mention. "Most people never really develop their weaker sides and concentrate on the stronger ones, but you seem to have done the former."

"I think that's what feminism is all about," John replies. "That's what Yoko has taught me. I couldn't have done it alone; it had to be a female to teach me. That's it. Yoko has been telling me all the time, 'It's all right, it's all right.' I look at early pictures of meself, and I was torn between being Marlon Brando and being the sensitive poet -- the Oscar Wilde part of me with the velvet, feminine side. I was always torn between the two, mainly opting for the macho side, because if you showed the other side, you were dead."

"On Double Fantasy," I say, "your song 'Woman' sounds a bit like a troubadour poem written to a medieval lady."

"'Woman' came about because, one sunny afternoon in Bermuda, it suddenly hit me. I saw what women do for us. Not just what my Yoko does for me, although I was thinking in those personal terms. Any truth is universal. If we'd made our album in the third person and called it Freda and Ada or Tommy and had dressed up in clown suits with lipstick and created characters other than us, maybe a Ziggy Stardust, would it be more acceptable? It's not our style of art; our life is our art.... Anyway, in Bermuda, what suddenly dawned on me was everything I was taking for granted. Women really are the other half of the sky, as I whisper at the beginning of the song. And it just sort of hit me like a flood, and it came out like that. The song reminds me of a Beatles track, but I wasn't trying to make it sound like that. I did it as I did 'Girl' many years ago. So this is the grown-up version of 'Girl.'

"People are always judging you, or criticizing what you're trying to say on one little album, on one little song, but to me it's a lifetime's work. From the boyhood paintings and poetry to when I die -- it's all part of one big production. And I don't have to announce that this album is part of a larger work; if it isn't obvious, then forget it. But I did put a little clue on the beginning of the record -- the bells... the bells on 'Starting Over.' The head of the album, if anybody is interested, is a wishing bell of Yoko's. And it's like the beginning of 'Mother' on the Plastic Ono album, which had a very slow death bell. So it's taken a long time to get from a slow church death bell to this sweet little wishing bell. And that's the connection. To me, my work is one piece."

"All the way through your work, John, there's this incredibly strong notion about inspiring people to be themselves and to come together and try to change things. I'm thinking here, obviously, of songs like 'Give Peace a Chance,' 'Power to the People' and 'Happy Xmas (War Is Over).'"

"It's still there," John replies. "If you look on the vinyl around the new album's (the twelve-inch single 'Just Like Starting Over') logo -- which all the kids have done already all over the world from Brazil to Australia to Poland, anywhere that gets the record -- inside is written: ONE WORLD, ONE PEOPLE. So we continue.

"The last album I did before Double Fantasy was Rock 'n' Roll, with a cover picture of me in Hamburg in a leather jacket. At the end of making that record, I was finishing up a track that Phil Spector had made me sing called 'Just Because,' which I really didn't know -- all the rest I'd done as a teenager, so I knew them backward -- and I couldn't get the hang of it. At the end of that record -- I was mixing it just next door to this very studio -- I started spieling and saying, 'And so we say farewell from the Record Plant,' and a little thing in the back of my mind said, 'Are you really saying farewell?' I hadn't thought of it then. I was still separated from Yoko and still hadn't had the baby, but somewhere in the back was a voice that was saying, 'Are you saying farewell to the whole game?'

"It just flashed by like that -- like a premonition. I didn't think of it until a few years later, when I realized that I had actually stopped recording. I came across the cover photo -- the original picture of me in my leather jacket, leaning against the wall in Hamburg in 1962 -- and I thought, 'Is this it? Do I start where I came in, with 'Be-Bop-A-Lula'?' The day I met Paul I was singing that song for the first time onstage. There's a photo in all the Beatles books -- a picture of me with a checked shirt on, holding a little acoustic guitar -- and I am singing 'Be-Bop-A-Lula,' just as I did on that album, and there's a picture in Hamburg and I'm saying goodbye from the Record Plant.

"Sometimes you wonder, I mean really wonder. I know we make our own reality and we always have a choice, but how much is preordained? Is there always a fork in the road and are there two preordained paths that are equally preordained? There could be hundreds of paths where one could go this way or that way -- there's a choice and it's very strange sometimes... And that's a good ending for our interview."

Jack Douglas, coproducer of Double Fantasy, has arrived and is overseeing the mix of Yoko's songs. It's 2:30 in the morning, but John and I continue to talk until four as Yoko naps on a studio couch. John speaks of his plans for touring with Yoko and the band that plays on Double Fantasy; of his enthusiasm for making more albums; of his happiness about living in New York City, where, unlike England or Japan, he can raise his son without racial prejudice; of his memory of the first rock & roll song he ever wrote (a takeoff on the Dell Vikings 'Come Go with Me,' in which he changed the lines to: "Come come come come / Come and go with me / To the peni-tentiary"), of the things he has learned on his many trips around the world during the past five years. As he walks me to the elevator, I tell him how exhilarating it is to see Yoko and him looking and sounding so well. "I love her, and we're together," he says. "Goodbye, till next time."

"After all is really said and done / The two of us are really one," John Lennon sings in 'Dear Yoko,' a song inspired by Buddy Holly, who himself knew something about true love's ways." People asking questions lost in confusion / Well I tell them there's no problem, only solutions," sings John in 'Watching the Wheels,' a song about getting off the merry-go-round, about letting it go.

In the tarot, the Fool is distinguished from other cards because it is not numbered, suggesting that the Fool is outside movement and change. And as it has been written, the Fool and the clown play the part of scapegoats in the ritual sacrifice of humans. John and Yoko have never given up being Holy Fools. In a recent Playboy interview, Yoko, responding to a reference to other notables who had been interviewed in that magazine, said: "People like Carter represent only their country. John and I represent the world." I am sure many readers must have snickered. But three nights after our conversation, the death of John Lennon revealed Yoko's statement to be astonishingly true. "Come together over me," John had sung, and people everywhere in the world came together”.

I am moving to some features about Double Fantasy. An album I heard a lot as a child, I do think that it is worthy of a lot more love and inspection. I think that John Lennon’s death recontextualised Double Fantasy. If some critics felt the songs were quite syrupy and Lennon moving towards the middle of the road and away from his best, I do think this is someone just in their forties reflecting on his life, family and love. I think it was not going to be the start of a new phase where subsequent albums sounded like this. I do feel Lennon would have become more experimental and followed Yoko Ono’s lead and influence. Double Fantasy is fascinating. In 2015, Ultimate Classic Rock write why Double Fantasy did not connect with many people at first:

“Charles Shaar, writing for NME, memorably said Double Fantasy "sounds like a great life, but it makes for a lousy record. ... I wish Lennon had kept his big happy trap shut until he had something to say that was even vaguely relevant to those of us not married to Yoko." Rolling Stone and the Village Voice, at least at first, weren't much kinder – and the record-buying public greeted the project with notable diffidence.

Double Fantasy, with its comfy domesticity and too-slick, of-its-moment production, never felt dangerous enough to be a top-tier John Lennon record. Well, at least half of the time. Yoko Ono, who was co-featured in an every-other-song format, took far more chances than he did.

It seemed, as much as anything else, like a record lost in time. Even the best of Lennon’s solo material after 1970’s Plastic Ono Band suffered from similarly dated, shag-carpet production. He loved a big sound, when sometimes a smaller one would have been more effective. Earlier in Lennon’s final decade, that meant pasting on herds of fiddles, a thudding drum clomp, gaggles of girl singers and bawdy, burlesque saxophones – something that must have brought him back to the '50s pop radio of his youth.

When Lennon returned to music after a five-year hiatus, he was still steadfastly double-tracking his vocals too. It afforded him a deeper, multi-layered sound but also needlessly softened the edges on one of rock music’s best sneers. Couple that with the compression typically employed back then, and Double Fantasy — considered apart from his death — often ended up more gossamer than necessarily great.

No matter. After Dec. 8, 1980, those earlier negative notices were forgotten as a funereal fervor pushed Double Fantasy to multi-platinum sales and a Grammy award for Album of the Year.

Seemingly forgotten was that Lennon, at his zenith, had been a scratched-and-dented treasure, laconic and all edge. Here, he seemed to have settled into a middle-aged tameness — both figuratively and, by employing the prevailing pop veneer, literally. That ultimately gave surprising gravitas to 1983’s Milk and Honey and 1986’s Menlove Ave., a pair of loose, unfinished posthumous follow-ups. (Yoko Ono added another edition to that collection when a stripped-down version of Double Fantasy was released in 2010.)

Only on the muscular “I’m Losing You” do you get the sense of Lennon's old sinewy grit. It's the most kinetic moment on Double Fantasy, and it points to the long-hoped-for return of Lennon’s muse — the vibrant, angry yang to the bread-making househusband yin of recent years. Unfortunately, little else rises so completely out of the project's cozy, contemplative vibe.

Of course, "Starting Over" and "Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy)" resonate in entirely new ways now. There's no getting away from the awful headlines that followed – no separating this album, even decades later, from Lennon’s fate. He’ll always be 40. So, when he whispers “Good night, Sean, see you in the morning” on the latter, it’s like a cold hand closing around any fan's heart.

Meanwhile, interspersing moments like "Woman," the record's most obviously Beatlesque ballad, with a series of nervy, New Wave-influenced Ono cuts certainly helps Double Fantasy live up to its subtitle: "A Heart Play." But it also underscores something about Lennon that his devastated followers weren't willing, or maybe even able, to admit.

While Lennon was making his way back into the business, Ono was far more in sync with the prevailing post-punk zeitgeist. Lennon was only just beginning to come to terms with things as they were — with middle age, with a settled life, with love and work and parenthood. How long could it have been before he was ready to push back, and hard? Unfortunately, we never got to hear his next great rock record”.

In November 2020, The Independent published a feature about Double Fantasy. Whilst it was not considered John Lennon’s best album, they are how it is his most personal. That is why it so meaningful to me. Jack Douglas produced Double Fantasy with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. At a time when Lennon was committing to a more domestic life and settling with family, Douglas did not expect to get the opportunity work with him. The start of the feature, where we learn how Jack Douglas got involved with Double Fantasy, is fascinating. I am starting with a passage further down. Selections from the feature that are especially relevant and interesting:

“Double Fantasy, released 40 years ago on 17 November, is not Lennon’s best album. But it may be his most revealing, for reasons that stretch beyond the music. For an artist who always wrote songs about his life, this record in particular - highlighted by “(Just Like) Starting Over”, “Woman” and “I'm Losing You” – is the most autobiographical of all. It also serves as an important, heartbreaking coda to a singular life. Lennon wanted Double Fantasy to restart his career. Instead, his tragic death, coming three weeks after its release, turned the music he made for the album into his final artistic statement.

Double Fantasy is the best way to tell the story of Lennon’s last years, from his retreat to house-husbandhood to his return to the top 10. It opens a window into the intense and often private relationship between Lennon and Ono.

“It's like a movie, though, and the script is constantly changing” is how Lennon explained it to Playboy’s David Sheff in an interview on the eve of the album’s release.

“We have some songs on the album that can be considered negative,” Ono added in the same interview, “but at the same time the fact that we can honestly state those feelings is very positive and we get a certain atonement for that.”

Double Fantasy is also, of course, not purely a John Lennon record. The decision to split it with Ono so completely – they would alternate songs – is the boldest play on an album that’s otherwise the slickest and most commercially focused of his career. In sharing the release, Ono and Lennon meant to create a kind of pop music diary of a relationship, or “heart play” as they called it. There was also a greater goal: to give Yoko access to the wider public.

Double Fantasy was meant to not just reinvent Lennon, the abrasive agitator turned doting dad, but also to recast Ono, who had been unfairly villainised as the woman who broke up the world’s biggest rock band. Her dissonant music was an acquired taste that had been widely mocked.

This is before digital playlists allowed us to self-edit. You could pick up the needle or fast-forward the cassette, but if you wanted your favourite Beatle’s latest release, you had to also take his wife as part of the purchase.

The dynamic with Ono did not go unnoticed. He seemed intent on using their relationship as a vehicle to reshape the traditional gender roles he had grown up with. When it came to Double Fantasy, she was an equal partner.

Which is why the “heart play”, as they called it, was both a concept and a reintroduction. Lennon and Ono’s relationship had always been shared, played out for the public.

In 1970, when the Beatles came apart, Lennon railed in Rolling Stone that they had “despised” Ono from the start and described Paul, George and Ringo as “the most bigheaded, uptight people on earth.” He also had little patience for fans who nostalgically longed for the mop tops of “She Loves You”.

In “God”, released on Lennon’s solo debut in 1970, he declared that “the dream is over” and detached himself from, among other things, magic, Buddha, Kennedy, Elvis, Jesus, Bob Dylan and The Beatles. “I just believe in me,” he sang. “Yoko and me.”

They wanted Double Fantasy to sell – they would tape the weekly Billboard chart to their bedroom door – but Lennon also wanted to deliver a message. The album had to update his sound and his image.

“This isn’t an album we want to sell to kids,” he told Douglas. “I’m going to be 40. This is an album we’re going to sell to the people who have been through the wringer of the ’60s and the ’70s. It's about a guy who’s married, whose life has changed. He’s cleaned up his act. And that’s what I want to say.”

Double Fantasy came out the third Monday in November. The reviews were mixed and sales were decent, if sluggish. At one point, Ono called Geffen with a plan to move more copies.

“She said, ‘I want you to go out and buy records at every record store,’” says Geffen. “She thought it could be operated, which it really can’t.”

On 9th October, we will mark John Lennon’s eighty-fifth birthday. I will publish another feature. However, for this one, I wanted to look at his final studio album. A very personal and revealing one that, despite some mixed critical reviews, I feel is thoroughly deserving of retrospection. When John Lennon was killed weeks after the album came out, Double Fantasy took on new perspective and meaning. Forty-five years after its release, I think Double Fantasy stands up. A sign of where, briefly, Lennon might have headed. Or maybe a stepping stone to other sounds. In my opinion, this 1980 release is a…

BEAUTIFUL album.