FEATURE:

Up the Hill Backwards

David Bowie's Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) at Forty-Five

__________

THIS album was released…

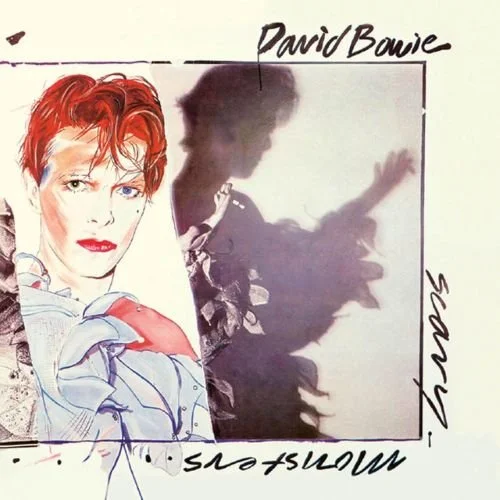

IN THIS PHOTO: David Bowie in 1980/PHOTO CREDIT: Brian Duffy

at a very interesting time. In terms of David Bowie’s career. His first album of the 1980s, Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) followed a year after Lodger. I think this was still part of a golden run of albums that began in 1977 with Low. Containing Bowie classics such as Fashion and Ashes to Ashes, it is no surprise that this album is seen as one of Bowie’s best. It turn forty-five on 12th September. Lodgers was the final album of his Berlin trilogy. Though these albums were not a huge commercial success, Low, “Heroes“ and Lodger are masterful albums from an artist at his peak. I do think that Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) is a little underrated in David Bowie’s cannon. As it turns forty-five on 12th September, I want to spend some time with it. I shall come to reviews for his fourteenth studio album. I am going to get to some retrospective features before coming to reviews. In 2020, Stereogum wrote how Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) summed up everything we knew about David Bowie. They erroneously argue that it was his last great album. That it was a creative peak that he never scaled again. Forgetting Bowie recorded several superb albums after that, including 1983’s Let Dance and 2016’s Blackstar:

“David Bowie’s Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) came out in September of 1980, 40 years ago tomorrow. And for 50 to 75 percent of the time since, it’s been known as “David Bowie’s last great album.” Retrospective reviews and biographies harp on it, while, naturally, every half-decent Bowie release in subsequent decades was proclaimed “the best album since Scary Monsters.” Many of Bowie’s generational peers have similar albums, but perhaps there was always something more glaring about it within Bowie’s career: The musician that once shed skins so easily, flailing through pop stardom in the ’80s and exploring new genres in the ’90s but never being able to live up to the groundbreaking work he did in the ’70s. Just before Bowie’s death, the transfixing mortality meditation of Blackstar may have finally rearranged things so that Bowie’s last album was also his last great album. But in the grand scheme of Bowie’s career, the story still pivots around Scary Monsters — the album that marks the end of at least one creative peak that now, having spent all these years with the burden of simply being the “last great album,” may also be an altogether underrated work in relation to the more canonized Bowie albums.

Scary Monsters arrived after the Berlin trilogy, an adventurous and massively influential stretch of albums that have only become more and more hallowed as the decades have passed. That era was obviously fruitful, but Bowie changed things up for Scary Monsters, decamping to New York and spending more time crafting the songs in an attempt to get something more direct. As a result, Scary Monsters would eventually be hailed as a successful marriage between Bowie’s experimental impulses and his songwriting acumen. Its infectious art-rock situated it perfectly at the dawn of new wave — a genre obviously heavily indebted to Bowie — yet at the same time it seemed to carry the whole preceding decade with it. It was a capstone, summary, and new beginning all at once, emerging from Bowie’s dizzying ‘70s run.

While Scary Monsters was a more grounded, rock-oriented album compared to its immediate predecessors, that was still only true relative to Bowie’s world at that moment. All of his transformations were swirling and colliding here. Glam rock songs were dressed up with hissing technological sheen. Remnants of the Thin White Duke’s plastic soul instead became the sound of melted plastic and warped, raw humanity. The chilly atmospherics of Heroes were now emerging into a new light, flashing and screaming and sputtering. The album seemed to underline how far Bowie had journeyed across the ’70s and how all of this somehow still lived within him. Hearing the different versions of Bowie at play on Scary Monsters can still, four decades later, make you reconsider his arc and inspire awe all over again that, say, “Rebel Rebel” and Low are separated by less than three years.

Yet in the overarching narrative of classic rock history, Scary Monsters might be beloved, it might be that last great album, but it’s not often mentioned as breathlessly as his theoretically more definitive albums — the widely accepted classic rock masterpiece of Ziggy Stardust, the psych-tinged soul reinvention of Young Americans paired with the nocturnal coke spiral of Station To Station, and then of course the genre-imploding and otherworldly Low and Heroes.

On some level this makes sense: The synthesis and refinement of things is rarely going to loom as large as the first, mind-blowing leap into unforeseen horizons. Even if Low and Heroes are half full-fledged (if askew) pop songs and half ambient excursions, they helped birth whole new genres. Scary Monsters, in comparison, was the sound of an aging Bowie more or less engaging with the new sound of the time — quite effectively, but no longer years ahead of everyone else. Still, Scary Monsters deserves credit beyond what it’s given: This is the less-heralded classic of Bowie’s career, taking everything about him and recontextualizing it within a jagged robotic aesthetic, all of it sounding like it took place in a nightclub in some retro-futuristic cityscape”.

The next feature I want to include is this from The Quietus. In their header, they write how, in “Silhouettes And Shadows, Adam Steiner takes a deep dive into a pivotal moment in the transformation of the Thin White Duke”. Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) is a pivotal album and a truly remarkable moment in David Bowie’s career. I feel it warrants a lot of new love and attention ahead of its forty-fifth anniversary:

“Bowie emerged blinking into the cold light of 1980 to find a new Britain. The election of a Conservative government seems to be the moment of first blood; death as rebirth, sparking his renewed interest in the growing discord reflected across society: “Scary Monsters always felt like some kind of purge," Bowie said in an interview with Bill Demain from 2003. "It was this sense of: ‘Wow, you can borrow the luggage of the past; you can amalgamate it with things that you’ve conceived could be in the future and you can set it in the now’”. This fed directly into Bowie’s continued fascination in post-apocalyptic scenarios, always jumping the gun to the greatest hits of the worst-case scenario –even Ziggy Stardust’s good time rolling in 1972 kicked-off with doom and gloom of ‘Five Years’.

From his review of Lodger, Jon Savage noted “a small projection from present trends, call it Alternative Present if you will,” in Bowie’s music. This granted him the perspective of an advanced future (present) tense, seeing through the everyday atrocity as if with a knowing sense of inevitability. Everything seemed to be running fast-forward, in free fall, accelerating toward the hyperreal technocratic state chained to the conspiracy theories of the military-industrial complex – the hunger for progress driven to a fever pitch at the bleeding edge of now. Viewed through the twisted prism of a thwarted political climate, everywhere Bowie looked, the world seemed full with clear and present dangers of terrorism and foreign conflict – some imagined, others very real – made manifest in the political rhetoric of Reagan’s “evil empires” and Thatcher’s “enemy within.” This weaponized language provided just cause for witch hunts to root-out the freaks, radicals, and rebels on the domestic front, to normalize the notion “war all the time” against one common (invisible) enemy after another – all for the preservation of Western conservative supremacy. Scary Monsters is infused with the same spirit of paranoiac doom-ridden rhetoric chattered among the political classes and echoed throughout sustained media bombardments; Bowie’s lyrics are flush with violence, broken bones, and damaged lives cut short. Where before Bowie had heard warning shots fired overhead, they now rained down as friendly fire from loose cannons and assassins, all with the deadly intent of the sniper picking off undesirables.

Where so many people’s inner lives hinged on daily uncertainties, the songs of Scary Monsters find Bowie setting himself against an unhinged global picture. His lyric notes express burning ambiguity mired in contradiction; for once, Bowie seems afraid to make the first move: “Half of me freezing, half of me boiling, I’m nowhere in between,” as Bowie seemed to write compulsively across his lyrical sketch sheets: “A reactive person … too much data, possible events.” Chris O’Leary hears the album as a singular “horror documentary,” the reel caught in its own teeth; phrases tumble out of him, spooling endlessly, turned over and over in a frantic mind as if overhearing oneself from another room: a wild terror, fresh heartbreak, psychic collapse.

Tired of occupying his station as the permanent outsider looking in, passing commentary on a planet that in many ways had always seemed alien and foreign to him, Bowie discovered a newfound need to reconnect with other people, though still focusing on himself as an introspective subject. Chris O’Leary noted that the David Bowie of 1980, whether by accident or design, found himself most at home in a “society of one.” The rising atomisation of the individual remained at the heart of Bowie’s music for several albums, charting humanity’s widening separation from common cause. In 1997, Bowie observed of himself, “Thematically I’ve always dealt with alienation and isolation in everything I’ve written.” Putting himself into the mind-set of loneliness as a place to write from, where small universes bloomed inside the mind, this act of self-distancing would increasingly become a mutual splintering disconnect. As Bowie watched the real-time heat-death of common mutuality, it seemed to confirm that alienation was simply a new expression of freedom (from others), so worldly concerns became centred around transactional analysis, individuals weighing the needs of their own lives against the invisible many. The decline of the nuclear family, rising divorce rates, and the carve-up of land and homes into ‘real estate’ spoke to private interest trumping collective responsibility, with each Englishman raising the drawbridge of his or her own castle. This confirmed the entitlement of a round-waisted petit bourgeois middle class, championing the climbing of the social ladder and the accumulation of “new” money to escape their past and avoid working-class associations, kicking the rungs out beneath them as they strained to climb ever higher.

Writer and journalist Jon Savage, who began as a music fan and became the man-on-the-ground chronicler of punk, noted the perilous times of 1980 in which Bowie had arrived. Still popular, it was as the glam rock entertainer that mainstream audiences and casual radio listeners valued him most. But now even his most outlandish tendencies had been absorbed into the new subculture. Bowie was no longer himself; he was “us,” standing at odds with the unsettled mood of the times, while the most radical of new musics that emerged in the brief renaissance of post-punk would gradually become less confrontational, more acceptable, and unthreatening as the decade wore on or remained underground as nonconformist subversion, somehow ruining the party: “In the face of increasing hardship and political polarisation, arty posing and homosex – inextricably linked too often thanks to Bowie’s example – are definitely seen to be out: the former as a childish luxury, the latter as a definite social disadvantage as dog eats dog.”

On Scary Monsters, there is a suppressed rage that mourned, mocked, and sampled the Bowie mythology, dissecting the beautiful corpse, still living. The faint and resigned “woah-ah-oh” line that ushers in the pre-chorus of ‘Ashes to Ashes’ is heard again on Tonight’s ‘Loving the Alien’, reaching strange heights of self-awareness but also managing to sound new and different and standing entirely in its own right. Elsewhere, Bowie blogger Neil Anderson points out that Bowie’s 1999 song ‘Pretty Things Are Going to Hell’ revisited the youthful spring of ‘Oh You Pretty Things!’ like ‘Changes’ in reverse, backward growth that interrogates images of the past. The sheer magnitude of Bowie’s back catalogue meant that he was weighed down by the number of songs and the refraction of images, making Bowie confront his many selves. As Greil Marcus noted, “Right at this point, then – the verge of the 80s – Bowie should be ready for a major new move, or a major synthesis”.

I will end with a couple of reviews for the amazing Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps). Rolling Stone provided their take on this David Bowie gem in 1980. I will also put in some links to a few rankings lists where we can see how this album is viewed. Whether it features among David Bowie’s ‘best’:

“On Scary Monsters, he comes out fighting. Fusing the sheet-metal textures of the Eno trilogy into something darker and more dense, Bowie focuses his attention on a world he helped create. Lodger, with its sardonic gambol through “the hinterland,” was the final serving — and sendup — of the old pose of evasive escapism. Scary Monsters presents David Bowie riveted to life’s passing parade: streamlined moderns, trendies and sycophants in 360 degrees of stark, scarifying Panavision. With its nervous voyeurism, Scary Monsters is more like Aladdin Sane (probably Bowie’s best record) than anything else. But because the bleakness that Bowie now witnesses is partially of his own devising, it gives the new LP a heavy, stricken pall. If there’s condescension in the artist’s stance (Prometheus aghast at what mortals have made of his gift?), there’s also genuine concern. Bowie has the air of a superhero who’s shrugged off his powers and thus volunteered himself to a reality from which he can’t quick-change away.

Claustrophobia descends immediately in the opening “It’s No Game (Part I),” which clanks and jerks its way into a lumbering, robotic dance. Bowie’s vocal — a long, distorted yowl of pain — is intercut with a harsh, rapid-fire Japanese translation. With its blunt rhythms, discordant accents and cautionary lyrics (“Throw the rock against the road and/It breaks into pieces…/It’s no game”), the song is meant to jolt and distress. The end is particularly disturbing. As the tune falls away, Robert Fripp’s stair-stepping guitar riff continues until the singer’s screams of “Shut up!” snap it to a halt — and you realize it was just a tape loop: mechanical companionship. It’s an ugly, disorienting moment. Scary Monsters is full of them.

Throughout the album, the beat is so jackbooted, the pressure so intense, you find yourself casting about for relief. Yet each hint of help (the ice-crystal space walk of “Ashes to Ashes,” the crooner’s catch to Bowie’s vocal in “Because You’re Young,” his failed leaps at a romantic falsetto in “Teenage Wildlife”) pulls you back into the same gray night-mare. The freeze-dried Bo Diddley riff that begins “Up the Hill Backwards” slashes into the middle of a bunch of swaying, arm-linked half-wits, who coo with the blank contentment of Brave New World some addicts: “More idols than realities/Oooh/ I’m O.K. — you’re so-so/Oooh/ It’s got nothing to do with you/If one can grasp it.”

David Bowie has always utilized distance for self-preservation, but now he’s shuddering at the results — at what happens when estrangement becomes not only an illustrative concept but a code to live by. The wraiths who inhabit Scary Monsters are all either running scared with their eyes closed or too wasted to notice what’s in front of them. They’re antiromantic, half-dead, disposable. “I love the little girl and I’ll love her till the day she dies,” Bowie leers in the title track, his exaggerated London accent a garish caricature of maudlin sentiment.

“Ashes to Ashes,” a sequel to “Space Oddity,” is Bowie’s most explicit self-indictment. Mirroring the malaise of the times, Major Tom — the escapist hero-has metamorphosed into a space-bound junkie, clinging hard to his pride and the fantasy that he’ll “stay clean tonight.” Though the image is chilling, it’s difficult to see “Ashes to Ashes,” with its reference to “a guy that’s been/In such an early song,” as anything but perverse self-aggrandizement. More successful is “Fashion,” a heavy-handed, irony-laden parody of stylistic fascism (“We are the goon squad/And we’re coming to town/Beep beep”), complete with handclaps and trendy buzz-and-whir accents. Hollow to the core, the tune is infectious enough to be a dance-floor hit, which will merely prove its point.

Terse, rocky and often didactic, David Bowie’s compositions cut away all illusions of dignity in isolation, of comfort in crowds. Even Bowie’s cover version of “Kingdom Come,” Tom Verlaine’s anthem about strife and salvation, is dark. He changes the heart-stopping shimmer of the original into a strained lock step. Verlaine’s affirming call-and-response (“I’ll be breaking these rocks/Until the kingdom comes”) is treated as a deadly joke. Bowie sings “Kingdom Come” in a flat, fake-naive drawl, and each line is answered — not with a promise but with a mock-gospel echo — by the lobotomized choir of “Up the Hill Backwards.” Since every last knee slap has been preplanned, it’s like a revival meeting in which nobody is transfigured. Any chance for redemption is out.

No one breaks through on Scary Monsters. No one is saved. Major Tom is left unrescued. The tortured, reprocessed gays of “Scream like a Baby” can’t save their friends — or their badge of difference. The human mannequins of “Fashion” can’t stop marching. Indeed, the kids in “Because You’re Young” can’t even tell each other apart Instead, beguiled by the hope of hope, they track the wasted remnants of romance (“A million dreams/A million scars”) until youth, too, is wasted.

Where do you go when hope is gone? Bowie’s enervated, meditative, half-speed reprise of “It’s No Game” leaves the question — and the record — hanging. The artist’s next album may see him questing, but on Scary Monsters, he’s settling old scores. Slowly, brutally and with a savage, satisfying crunch, David Bowie eats his young”.

The Treble posted their review of Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) in 2008. For anyone who has not heard this album, I would advise you to spend some time with it. It is a remarkable album that perhaps came at the end of the greatest run of his career. However, it was definitely not David Bowie’s last truly ‘great’ album:

“It’s no wonder, considering the panic and emotion he goes through in the center of the album. “Scary Monsters” keeps up a paranoid atmosphere, where Robert Fripp’s guitar work squeals as you picture spidery, Nosferatu fingers reaching for the girl left “stupid in the street” who can’t socialize. Though it’s Bowie who says he’s running, you’re left to question who the vampire is here: “She asked me to stay and I stole her room / She asked for my love and I gave her a dangerous mind.” It should be noted that his vocals, when not sounding tortured, tend to have an almost mechanical inflection adding to the creepiness of this song.

The next two songs are probably the most well-known from the album: “Ashes to Ashes” and “Fashion.” They’ll both end up on repeat, though they’re very different kinds of songs. “Ashes,” often speculated to be Bowie’s drug confessional, is a wash of trippy, plunking effects, with the lyrics whispered behind Bowie’s singing. “Ashes to ashes / funk to funky / We know Major Tom’s a junky / strung out in heaven’s high, hitting an all-time low” seems to speak more to Bowie’s past than his recent drug addictions. Glam’s most-celebrated chameleon has a wax gallery of personas, all of them worshipped throughout the 1970s. In “Ashes,” Bowie seems to be saying goodbye to all of them: “My mother said, to get things done / you better not mess with Major Tom.” He’s moving on here, and, appropriately, Scary Monsters is recognized as a fusing together of his disparate styles and sonic experiments leading up to 1980.

“Fashion” heads off in a different direction altogether. It’s more a straightforward dance song, with a killer beat and funk-filled bass line. The imagery that comes to mind is an army of metrosexual robots, dapper, hip, and completely brainless: “We are the goon squad and we’re comin’ to town – beep beep!” Despite the dark lyrics, it’s irresistibly catchy, and perfect for any dance party.

The last standout song is “Teenage Wildlife,” almost an open letter to the aspiring pop cretins following in Bowie’s footsteps. Flocks of lonely teenagers and make-up-wearing rock Lotharios have prayed at the shrine of Bowie since his rise to stardom. Now estranged from his glittering costumes, Bowie has little in common with these starry-eyed performers, seeking advise on how to be rich, famous and well-loved: “A broken-nose mogul are you / One of the new wave boys / Same old thing in brand new drag comes sweeping into view / ugly as a teenage millionaire.” It’s a coming to terms with the wonderland he’d been floating through most of his young adulthood. But as fun as the fame and spotlight have been, it’s hard not to be sick of fans hanging on to his every word – with famous fans now trying to pen words like his. Bowie was earning his freedom here, asserting that he’s a man and an artist, but not “a piece of teenage wildlife” to be hunted, trapped, and prodded to perform.

The ’80s would be a quagmire for his career, and the ’90s, though he’d receive more attention, were uneven as well. Yet in the ’00s, albums like Heathen and Reality proved he still had an eclectic range in him, on up through the triumph of The Next Day and, ultimately, Blackstar. Bowie’s public remained relatively quiet following Scary Monsters, when he closed the door on his wild, fanciful menagerie of space aliens and cracked actors. But he closed it with a bang, and it holds up remarkably well even decades after its release”.

Last year, Rough Trade rankled David Bowie’s albums and placed it first. In 2013, Rolling Stone placed Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) in seventh (“There really isn't a weak track on the album, proving that Bowie was almost unique among Seventies rock icons in his ability to stay relevant after the punk revolution. He made many great songs after this, but never again was any album this satisfying from start to finish”). SPIN also placed the album seventh in their ranking from 2022. I shall end things there. A true David Bowie classic, Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) turns forty-five on 12th September. A masterpiece from an icon that…

WE very much miss.