FEATURE:

When You Can Dance I Can Really Love

Neil Young’s After the Gold Rush at Fifty-Five

__________

THE third studio album…

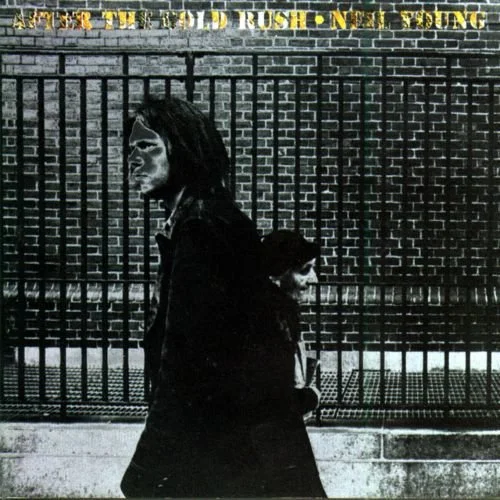

IN THIS PHOTO: Neil Young rehearsing backstage in Philadelphia in 1970/PHOTO CREDIT: Joel Bernstein

from Neil Young, After the Gold Rush was released on 19th September, 1970. Déjà Vu was the second studio album released by Crosby, Stills & Nash, and the first as a quartet with Neil Young. It is really interesting hearing the albums stand up against one another. Neil Young wrote Helpless and Country Girl for Déjà Vu. He co-wrote Everybody I Love You with Stephen Stills. However, After the Gold Rush is a singular effort. Except for a cover of Don Gibson’s Oh, Lonesome Me, this is Neil Young in full flight. After the Gold Rush, Southern Man, and Don’t Let It Bring You Down among the highlights. The album reached number seven in the U.K. and number eight on the US Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart upon its release. I wanted to mark the upcoming fifty-fifth anniversary of a classic album. I will come to a couple of features about After the Gold Rush. In 2015, on its forty-fifth anniversary, Ultimate Classic Rock & Culture discussed the album and its background. How Neil Young turned After the Gold Rush into a '60s requiem:

“Released on Sept. 19, 1970, it's also the end of an early chapter in Young's career. After breaking from Buffalo Springfield and releasing his debut solo album in 1968, the singer-songwriter would begin what would become the first of many career left turns. On 1969's Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, he plugged in and scraped away at the scabs with the young Crazy Horse.

But by the following year, when he was set to make a follow-up LP, he had fired them (but retained a few songs they had already laid down) and retreated to his basement in Topanga, Calif., where he started recording tracks for the follow-up record, a 360-degree turn into acoustic country and folk music with a group of musicians whose approach was a bit more delicate.

Rubbing against the plugged-in numbers left over from the Crazy Horse sessions, the new songs – which featured 18-year-old Nils Lofgren on guitar and piano, an instrument he was mostly unfamiliar with – helped create a ragged and almost disjointed record that's never quite sure if it's electric or acoustic, part of the '60s or part of the '70s.

And it's a brilliant juxtaposition, one that gives After the Gold Rush a feeling of frustration and resignation. It's a romantic album too – the soft "Only Love Can Break Your Heart" is a highlight – but the sting of "Southern Man," which immediately follows in the track listing, tempers the mood.

The entire album is like that: soft, hard. Quiet, loud. Acoustic, electric. It's almost as if Young was carrying around too many ideas – his first album with Crosby, Stills & Nash, Deja Vu, had only come out in March – and decided to pour them all out onto a 35-minute LP that serves as both a literal and metaphorical link between the abrasive Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere and the plaintive Harvest.

But more than any of this, After the Gold Rush puts an end to '60s idealism through a mix of songs that cut specifically – the meditative title track, a piano-driven ballad that ranks among Young's very best – and more abstractly (the album's opening cut, "Tell Me Why") into the deep, overriding sorrow that runs throughout the record. "Look at Mother Nature on the run in the 1970s," he sings on "After the Gold Rush," pretty much sealing a fate nine months into the new decade.

After the Gold Rush became Young's first Top 10 album, making it to No. 8 (he'd score his only No. 1 two years later with Harvest). Two singles were pulled from the record – the acoustic waltz "Only Love Can Break Your Heart" and "When You Dance I Can Really Love," recorded with Crazy Horse – but neither cracked the Top 30. It eventually sold more than two million copies.

And it remains one of Young's greatest works, a summation of his career up to that point and a sign of things to come. He'd explore the album's two opposing sides many times over the years, sometimes together (like on 1979's Rust Never Sleeps) but more often on separate projects that occasionally struggled to make sense of his whims and genre jumping.

One of the most fascinating aspects of After the Gold Rush is how and where it was made. Having listened to the album for decades, I was not aware of its recording and the conditions Neil Young was recording in. Maybe repeating some of the feature above, Classic Album Sundays told the story of After the Gold Rush in their article. Two years on from After the Gold Rush, Neil Young released another masterpiece with Harvest. Many argue, though, that After the Gold Rush is Neil Young’s finest work:

“Young’s dogged self-determination, despite its interpersonal downfalls, was a major artistic virtue that fed directly into what was perhaps his first true masterpiece. After The Gold Rush had its beginnings in an unlikely place. Dean Stockwell, a former child star of the ‘40s and ‘50s, had been encouraged by his friend Dennis Hopper to write a screenplay whilst the pair were in the jungles of Peru producing a film entitled The Last Movie. Hopper assured Stockwell that he had the relevant connections to help get the film made, and once back in the US the latter retreated to his home at Topanga Canyon in the Los Angeles Mountains to commence the writing process.

A fellow resident of the canyon and a close friend of Stockwell’s, Young was suffering through a prolonged period of writer’s block and was under growing pressure from his label to record an album of new material. After learning of the writer’s creative endeavour he was intrigued to learn more and asked Stockwell if he could read a draft of the story. The script, which has since been lost, was an unconventional, non-linear narrative with religious and psychedelic undertones. It loosely detailed an end-of-the-world scenario centred on the local Californian environment, in which a biblical flood threatened to pull the state into the ocean. Captivated by this messy but intriguing tale, Young recalls: “I was writing a lot of songs at the time, and some of them seemed like they would fit right in with the story.”

Ironically Hopper’s proximity to the project scared off any interested executives, and before long the film seemed destined to remain in limbo. Nonetheless, Young was fired up and undeterred, commencing work immediately on what he imagined to be the soundtrack of this deeply counter-cultural Hollywood film. Finding time to write and record was difficult, as large swathes of 1970 were blocked out by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s huge US Tour and further live obligations with Crazy Horse. In the precious gaps between shows, Young made initial recordings at Hollywood’s Sunset Studios, yielding “I Believe In You” and “Oh Lonesome Me” but quickly realised he preferred the atmosphere of the Canyon, continuing the process at the home studio set up in his lead-lined basement. It was here that his ensemble of bassist Greg Reeves, drummer Ralph Molina, and guitarist Nils Lofgren assembled.

The studio was a small and sweaty space, adjoined to a side control room from which producer David Briggs kept an eye on proceedings. The youngest of the ensemble, eighteen year-old Lofgren was brought in to play keyboards despite being a relative novice at the time of recording, highlighting Young’s unconventional laid back approach. Accordingly the musician recalls that “Neil didn’t mind rehearsing a bit” but they “didn’t belabour stuff.” It’s often considered that Young was attempting to merge musicians from both Crosby, Stills & Nash and Crazy Horse on this album, and Stephen Stills even appears on “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” to provide backing vocals.

The basement’s make-shift setup influenced the stark and plaintive sound of After The Gold Rush. Young featured solo on piano throughout the album, most notably on the title track which is often praised as the centrepiece of the album. Charting a surreal and fantastical course through three verses, the song starts in a medieval era of knights and peasants and ends in outer space with the remnants of humanity, after the world has descended into apocalypse”.

There are some reviews I want to end with. For Audioxide, André Dack, Frederick O'Brien and Marcus Lawrence penned their views on 1970’s After the Gold Rush. I want to share Dack and O’Brien’s assessment of one of the best albums of the 1970s. A sublime and mesmerising album that has touched so many people through the decades:

“André

After the Gold Rush is Neil Young at the absolute top of his game. It’s a masterpiece, plain and simple. His third studio album is as accomplished as any he’s ever released: an astonishing feat given he was only 24 years of age at the time. After the Gold Rush is a tight package that displays extreme versatility, covering an extraordinary range of musical ground and lyrical depth. Provocative rock jams with soulful guitar solos stand alongside romantic country ballads and heart-warming numbers led by playful piano.

For all its musical and personal scope, Young does incredible things with, seemingly, so little. Simple vocal melodies sung over elementary chords have no right to be as effective as they are here, but Young has the capability to floor listeners with his presence. If there’s an album that best showcases Young as a songwriter, After the Gold Rush is the most immediate choice. His poetry comes naturally, with no metaphor feeling forced. His personal musings and intricate stories aren’t bound by genres. Though his folk and country background is well known, Young’s songs transcend these origins. This is music for everyone.

It’s crucial to recognise that Young has been aided by some of the most extraordinary backing bands that contemporary music has ever seen. After the Gold Rush now celebrates its 50th anniversary, which is absurd given these songs do not sound like they were conceived half a century ago. There are a number of reasons for this, but most notable are the incredible arrangements that comprise the albums deeper cuts. The extraordinary tale of “Southern Man” is driven by stirring guitar, percussive piano parts, and the most glorious vocal harmonies you can ever dream of. It’s the kind of thing Radiohead have been replicating throughout their illustrious career.

“Don’t Let it Bring You Down” is another gem in this respect, showing the full force of the piano as an accompanying instrument. It puts many modern arrangements to shame. Young’s versatile vocals add a sprinkling of magic to these songs that propel them to legendary status. Whilst Bob Dylan’s voice has been a note of contention throughout the years, there’s simply no denying Young’s abilities. At its best, his voice smoothly sails through the mix like a delightful breeze, meaning that the music is not just magnificent, but accessible too.

Sounding as good as ever, After the Gold Rush remains one of the definitive albums released by, quite possibly, the greatest singer-songwriter we’ve ever seen. To those looking to probe Young’s daunting discography: start here.

Favourite tracks //

Southern Man

Don't Let It Bring You Down

Oh, Lonesome Me

9 /10

Fred

Reviewing albums of this calibre is a bit of a double-edged sword. They’re a delight to listen to, and writing about them almost feels redundant. What is there to say about After the Gold Rush that hasn’t been already? It’s vintage Neil Young, as fine a blend of rock, blues, and country you’re ever likely to hear. Beautifully produced too, which always helps.

I suppose the best I can do is put the record in context with the other Young release we’ve reviewed. On the Beach is my favourite Neil Young record, and one of my favourite records ever. After the Gold Rush is not On the Beach. They’re different animals. This is a more jumbled, less miserable affair. The songs have a spring in their step, the zest of a born traveller going it alone. The record is an ideal introduction to Neil Young in that sense; it’s super accessible.

There are a good few classic tunes crammed into the 35-minute runtime. “Southern Man” is a one-inch-punch of a song, with low key one of the greatest rock solos going. The cover of “Oh, Lonesome Me” is so pathetic that it becomes kind of adorable, like Droopy the dog in musical form. The songs are eclectic, but they’re held together by the band which, with a few Crazy Horse members among their ranks, accompanies Young beautifully.

Young has always had a lightness that makes him more approachable than the icier singer/songwriter greats, be they Bob Dylan or Laura Marling. Few — if any — albums showcase that wamth better than After the Gold Rush. It’s Young on a roll, with a fire in his belly and love overflowing from his big Canadian heart. Half a century on, it remains a joy.

Favourite tracks //

Southern Man

When You Dance I Can Really Love

Don't Let It Bring You Down

9/10”

I am going to end with AllMusic and their five-star review of After the Gold Rush. On 19th September, this phenomenal album turns fifty-five. I am not sure whether there will be new features and retrospectives. Perhaps a fifty-fifth anniversary is not as big as a fiftieth or even a sixtieth. However, I do hope that some take the time to share some thoughts and insights. After the Gold Rush is an album that needs to be shared and heard by the new generation:

“In the 15 months between the release of Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere and After the Gold Rush, Neil Young issued a series of recordings in different styles that could have prepared his listeners for the differences between the two LPs. His two compositions on the Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young album Déjà Vu, "Helpless" and "Country Girl," returned him to the folk and country styles he had pursued before delving into the hard rock of Everybody Knows; two other singles, "Sugar Mountain" and "Oh, Lonesome Me," also emphasized those roots. But "Ohio," a CSNY single, rocked as hard as anything on the second album. After the Gold Rush was recorded with the aid of Nils Lofgren, a 17-year-old unknown whose piano was a major instrument, turning one of the few real rockers, "Southern Man" (which had unsparing protest lyrics typical of Phil Ochs), into a more stately effort than anything on the previous album and giving a classic tone to the title track, a mystical ballad that featured some of Young's most imaginative lyrics and became one of his most memorable songs. But much of After the Gold Rush consisted of country-folk love songs, which consolidated the audience Young had earned through his tours and recordings with CSNY; its dark yet hopeful tone matched the tenor of the times in 1970, making it one of the definitive singer/songwriter albums, and it has remained among Young's major achievements”.

Frequently voted among the best albums of all time, After the Gold Rush sits alongside the all-time best Neil Young work. It may be his very best release. Still touring and recording to this day, his forty-ninth studio album, Talkin to the Trees, released under Neil Young and the Chrome Hearts, came out in June. Fifty-five years after its release, and Neil Young’s masterpiece After the Gold Rush…

CONTINUES to shine.