FEATURE:

Something Changed

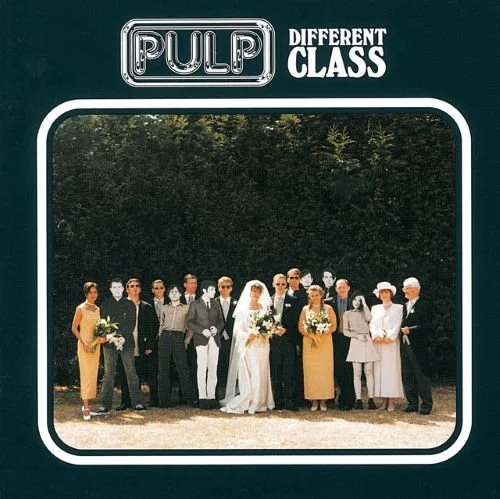

Pulp’s Different Class at Thirty

__________

IT is great to…

talk about a band’s classic album when they are still together. Few would have imagined that the Pulp we heard in 1995 would still be together thirty years later. On 30th October, Pulp’s fifth studio album turns thirty. Following 1994’s His ‘n’ Hers, this was part of a golden run for Pulp. Not that they were finding their feet – as they had been around for years -, but it is clear that this band were at their peak. It is no wonder that Different Class was a massive success. Reaching number one in the U.K. and winner of the 1996 Mercury Music Prize, since then, Different Class has been ranked alongside the best and most influential albums ever. There is a thirtieth anniversary edition coming soon. NME reported the story:

“Now, to mark its 30th anniversary, the Sheffield band have announced details of an expanded reissue, to be released as both a quadruple LP set and as a double CD. It will be out on October 24 via Universal Music Records on behalf of Island Records and you can pre-order your copy here.

The release will include the full performance the band gave as Pyramid Stage headliners at Glastonbury 1995, an iconic set that came several months before the release of ‘Different Class’, after they were asked to fill in for The Stone Roses with just 10 days notice.

Speaking about the release, frontman Jarvis Cocker has said: “This 45rpm double album version of ‘Different Class’ will make it sound a whole lot better. We were obsessed with the fact that this was our ‘Pop’ album (we had finally achieved some ‘popularity’ when ‘Common People’ was a hit) &, as everyone knows, all pop albums have 12 songs on them: 6 tracks per side.

“Only problem: this took the running time of the record to 53 minutes. We were told this would compromise the audio quality of the vinyl record – but we were more bothered about not compromising the quality of our Pop Dream. Now, 30 years later, we are finally ready for ‘Different Class’ to be heard in all its glory. Different Class indeed”.

To mark thirty years of a landmark album in British music, I will explore a few features about it. A review that highlights the brilliance of Different Class. Rather than bring in some archive interviews, I want to get to some features to start us off. In 2015, NME provided an oral history of Different Class. I was twelve in 1995, so I recall how Different Class was being talked about. It is a fascinating album that was everywhere in a year when British music was incomparable:

“With ‘His ‘N’ Hers’ spawning Top 40 hits in the form of ‘Do You Remember The First Time?’ and ‘Babies’ (on its re-release), Pulp had emerged after 15 years in the indie gutter as pivotal movers and shakers of the Britpop scene. The sudden attention, however, struck Jarvis Cocker as odd after so many years as a waggle-fingered wannabe.

Jarvis Cocker (Pulp singer): “The first time the fame things really struck me was when I was on holiday in the south of England, and these big blokes would lumber up to me and I’d think, ‘Oh shit, I’m in for a right hammering here for looking like a weirdo,’ and they’d shake my hand and say, ‘Like your song, mate’. That was nice… Of course, as soon as I get used to it, some big bloke will lumber up to me, I’ll say, ‘Hello, who shall I sign the autograph to?’ and he’ll twat me for being a weirdo. There was a time when I was quite paranoid about going out. Not really getting hassled but, even if people don’t say anything to you, you can still see them nudging each other going, ‘Oh, ’e’s ’ere’, and it’s just like, ‘I just fancied a drink, really’. But I don’t complain about it, because I used to do it myself if someone famous walked in. It’s like what people say if there’s a disaster: ‘I never thought it would happen to me’.”

Melissa Laurie (Pulp’s PR in 1995): “Everybody was quite surprised, the way things were going. Pulp had spent a long time in the wilderness. There were loads of people saying, ‘They’re really old, they’re never gonna do it, they’ve been going round for years’. There was a sense of, ‘Is it really happening?’”

Jarvis Cocker: “You can kind of lose it, because people let you get away with murder, ’cos you’re a famous person. So, if you’re not careful, you can turn unto a really horrible person, just because you can take advantage of people all the time… I’ve always tried to strive to be as irresponsible as I possible can, so it’s difficult to discipline yourself”.

The first glimpse of material from Pulp’s fifth album came over the summer of 1994, when ‘Common People’, ‘Disco 2000’ and ‘Underwear’ began appearing in festival sets. But Pulp’s star really ascended, however, with the runaway Number Two success of ‘Common People’, which captured the musical and political tone of the decade (pop, anti-Tory) with its euphoric melodic crescendos and sharp-witted defiance of class tourist snobbery”.

Spotlighting twenty-five years of Pulp’s Different Class in 2020, Guitar.com commended the genius of a seismic album. One that I think altered the course of the band and those around them. Those who think Different Class is not a guitar album should rethink. This feature highlighted an album filled with “songs about love, class and leaving an important part of your brain somewhere in a field in Hampshire”:

“You might think that Different Class is not a guitar-centric album, Doyle’s Farfisa organ responsible for many of its signature hooks, but there are tonnes of guitar tracks on the record. Russell Senior used his Fender Jazzmaster throughout the sessions; Mark Webber, who’d joined the band earlier that year, played a Gibson ES-345, Les Paul and Firebird and Cocker, a seriously underrated player who according to engineer David Nicholas laid down a significant chunk of the guitar work on the record, a Vox Marauder, Ovation-12 string and Sigma acoustic. When it came to Common People, a surging multi-layered opus that gallops breathlessly from 90bpm to somewhere around 160, Cocker’s decision to add one more part to the puzzle proved crucial. Thomas having filled all 48 tracks on the desk, Cocker decided to put down an acoustic guitar part using his Sigma. “It brought the whole track together,” remembered the producer. “It was just a brilliant idea. That acoustic guitar just welded all these disparate elements together.”

“Jarvis is an incredible guitarist and I recorded him with the same mic that I used to record his vocal,” remembered engineer David Nicholas of the one-take contribution that transformed the song into a hit.

Elsewhere, there’s the the glorious strutting (F/B♭) riff that provides the basis for the wistfully nostalgic Disco 2000; and listen out in the sweeping Serge Gainsbourg-esque Live Bed Show for the sizzling EBow part. The utterly gorgeous Something Changed, carried by rich open chords, a strummed acoustic rhythm and an inspired strings section, has a delightful solo and even ode to raving Sorted For E’s & Wizz is underpinned by the crisply strummed Sigma. The dark, cinematic epic F.E.E.L.I.N.G.C.A.L.L.E.D.L.O.V.E. presaged the shadowy post-Britpop comedown of 1998 follow-up This Is Hardcore, while the dubby Monday Morning has a darting riff that frolics joyously around Cocker’s vocal. Pulp’s three guitar players were absolutely essential to Different Class”.

I will come to a review soon. However, I found this feature from Stereogum from 2015. There will be a lot of new articles written about Different Class ahead of its twentieth anniversary on 30th October. Before coming to a final feature, I would advise people check out this one, that looks at a singular album that still sounds incredibly fresh, intriguing and filled with interesting people. I think it is the people, in the songs and on the cover, that has provoked so much discussion and theories. These visions and songs that tell these stories that so many people can relate to:

“Different Class represents the weird sort of magic that can happen when a band takes nearly two decades to find its voice. The Pulp of Different Class weren’t musically bright and brash, the way their Britpop peers were. Instead, they were slick and intricate and gauzy and atmospheric, picking up tricks from Serge Gainsbourg and Angelo Badalamenti and Lodger-era Bowie rather than Slade and Madness and Ziggy Stardust-era Bowie. Cocker might’ve been gawky and professorial in person, but he’s built up the confidence needed to sound like absolute sex on record. On Different Class, he manages to be flirty and creepy and charming and just slightly dangerous, often all at once, and it does it all while telling these grand and considered stories. The lyric sheets of Pulp’s records famously included a request: “Please do not read the lyrics whilst listening to the recordings.” Different Class is the moment that Cocker earned our compliance.

In the past year, there have been a couple of news stories about Pulp that weren’t really about Pulp. Instead, they were about women that Jarvis Cocker was singing about on different songs from Different Class, the Pulp masterpiece that turns 20 today. First story: A pioneering mental health worker, the woman Cocker was singing to on the song “Disco 2000,” died of bone marrow cancer at the way-too-young age of 51. Her name really was Deborah, and we’ll have to take Cocker’s word that it never suited her. Second story: A Greek newspaper reported that it had figured out who Cocker was singing about on “Common People,” reporting that the only woman who’d come from Greece with a thirst for knowledge and studied sculpture at St. Martin’s College, at least when Cocker was also studying there, was actually the wife of the current Greek Minister of Finance. (She must have a thing for elegant fuckups.) Cocker had once said that “Common People” was about a real woman but admitted that she hadn’t pursued him but that he’d pursued her. Both of these stories resonated in odd ways, at least to me, mostly because it had never occurred to me that Cocker was singing about real people. Instead, Deborah and the woman from Greece were pure abstractions, rendered through Cocker’s point-of-view, made to stand for things like upper-class privilege and the longing that can come from a platonic friendship. But it should’ve always stood to reason. The Cocker of Different Class was such a pointed and specific observer of human nature that it only makes sense that he’s lived his stories. And so maybe every song on Different Class is about a different real person or a different real experience. Still, finding out that the woman from Greece was a real person was like learning that Larry David is the real George Costanza. It makes perfect sense at the same time that it annihilates a whole fictional universe”.

In 2020, the BBC told the story of Different Class and discussed its impact. An album that documented modern Britain in 1995 and, then and now, does. I will pick up the article from the point where it talks about Common People and its success. It is great reading about Pulp briefly reforming and playing together but essentially that was it. Now, with them in the spotlight with a new album, this year’s More, it gives Different Class new context and weight:

“On Common People Cocker tore into class tourists, inspired by a well-to-do Greek girl he met at Central Saint Martins who wanted to try slumming it in Hackney for a while – “smoke some fags and play some pool, pretend she never went to school”. Hidden underneath those irresistible pop hooks is a mounting anger not just at her but all those who co-opt a working-class identity as a shortcut to authenticity – without ever dealing with the fear, uncertainty and absence of choice that comes with having no money. Towards the end of the song Cocker is practically spitting. “You will never understand how it feels to live your life with no meaning or control, and with nowhere left to go”.

His anger is even more palpable on I Spy, a song in which someone who has nothing observes those who have everything – all the while plotting how to “blow [their] paradise away”. While fantasising about how he’ll infiltrate this Ladbroke Grove life, he compares his own: “My favourite parks are car parks. Grass is something you smoke, birds are something you shag. Take your Year in Provence and shove it up your ass.”

Pulp had spent most of their lives on the outside looking in, making them the perfect champion of the disempowered

But if a young Cocker thought the odds were stacked against him in the 80s and early 90s, he’d be even more raging now. Class privilege – especially in the arts – has only worsened. Last year, research by Sutton Trust and Social Mobility Commission found that 20% of British pop stars were privately educated (compared with 7% of the general population). Figures from 2018 showed that just 44% of the intake at the Royal Academy of Music came from state schools, with the Courtauld Institute of Art only slightly better at 55%. “A bunch of young working-class kids from the north really storming into the charts and onto the front pages of the papers… back in the 90s it was hard,” says Banks. “It seems almost impossible now.”

Pulp had spent most of their lives on the outside looking in, making them the perfect champion of the disempowered. “Being able to observe without being observed yourself, you get to see the real sort of underbelly or workings of what goes off in life,” says Banks.

No detail passed Cocker by, from “the broken handle on the third drawer down of the dressing table” (F.E.E.L.I.N.G.C.A.L.L.E.D.L.O.V.E) to the “woodchip on the wall” in Disco 2000. His stories were specific, but reflected a wider society, too – as in Sorted for E’s and Whizz, a song inspired by Cocker attending raves in the late 80s. “Is this the way they say the future’s meant to feel, or just 20,000 people standing in a field?” With illegal raves now on the rise again in the UK, he could easily be talking about 2020, not 1988. In fact, aside from calls to “meet up in the year 2000”, so much of the album and its themes of being young and out of options feels pertinent in the current day.

The album reached number one and went on to win the Mercury Music Prize. A sell-out arena tour followed. Pulp were no longer the outsiders. It felt good – to begin with, at least. “When you’ve been in the desert so long and you reach the oasis you jump in and fill your boots,” says Banks.

Cocker had achieved his lifetime ambition to be a pop star – but he would later liken it to “a nut allergy”. The infamous 1996 Brit Awards, where he ran onstage during Michael Jackson’s performance of Earth Song to wiggle his bum to the audience – and ended up getting arrested on suspicion of assault (it was video footage captured by David Bowie’s team that got him off the hook) – turned the dream of pop stardom into a nightmare. Speaking recently to the New York Times he said: “In the UK, suddenly, I was crazily recognised and I couldn’t go out anymore. It tipped me into a level of celebrity I couldn’t ever have known existed, and wasn’t equipped for. It had a massive, generally detrimental effect on my mental health.”

His disillusionment – repulsion, even – with fame, played out on Pulp’s next album, This Is Hardcore, a record about “panic attacks, pornography, fear of death and getting old.” On opener The Fear, he sang: “This is the sound of someone losing the plot/Making out they’re OK when they are not”. If Britpop was already halfway out the door, this album gave it one last brutal kick to see it on its way.

“At the time we just laughed at [Britpop],” says Banks. “We’d been lumped in with many, many scenes over the years. We just couldn't relate to it, we weren’t bothered and the nearest we were to Britpop was Russell [Senior] wearing some Union Jack socks. It was always labels that other people foisted upon us.”

After releasing their seventh album, the Scott Walker-produced We Love Life, in 2001, Pulp went on hiatus for a decade, reforming in 2011 for a series of live dates. They played their last gig – for now at least – in their hometown of Sheffield in December 2013”.

If people celebrate Different Class and very much frame it around Common People, it is worth noting how strong the entire album is. How many gems there are. From Bar Italia to Mis-Shapes to Something Changed. There is not a weak moment on the album. Every song tells a story and forms this incredible and hugely memorable whole. In 2016, Pitchfork published their review of Different Class. There are some interesting observations:

“Cocker’s ambivalence about the masses also informs “Sorted For E’s & Wizz,” which—with “Mis-Shapes” as its double A-side—became Pulp’s second UK No. 2 hit of 1995. A wistful flashback to the illegal outdoor raves of the late ’80s and early ’90s, “Sorted” sees Cocker swept up in the collective celebration yet remaining deep down a doubtful bystander. “Is this the way they say the future's meant to feel?” he muses disconsolately, “or just twenty-thousand people standing in a field?” As the Ecstasy wears off and dawn peeks grimly over the horizon, Cocker finds the sensations of unity and bonhomie to have been ersatz and ephemeral: not one of the ultra-friendly strangers he’d bonded with earlier in the night will give him a lift back to the city. Still, he can’t quite shake the lingering utopian feeling that divisions of all kinds really were magically dissolved for a few hours. In the CD single booklet, a four-word statement of perfect ambiguity spells out his sense of rave’s fugitive promise: “IT DIDN'T MEAN NOTHING.”

Class is far from the only theme bubbling away in this album, though. At least half the songs continue the love ‘n’ sex preoccupations of His ‘N’ Hers, tinged sometimes with the yearning nostalgia of earlier songs like “Babies.” The treatment on Different Class ranges from saucy (“Underwear”) to seedy (“Pencil Skirt,” the hoarsely panting confessional of a creepy lech who preys on his friend’s fiancé) to the sombre (“Live Bed Show” imagines the desolation of a bed that is not seeing any amorous action). “Something’s Changed,” conversely, is a straightforwardly romantic and gorgeously touching song about the unknown and unknowable turning points in anyone’s life: those trivial-on-the-surface decisions (to go out or stay in tonight, this pub or that club) that led to meetings and sometimes momentous transformations. Falling somewhere in between sublime and sordid, the epic “F.E.E.L.I.N.G. C.A.L.L.E.D. L.O.V.E” exalts romance as a messy interruption in business-as-usual: “it’s not convenient...it doesn’t fit my plans,” gasps Cocker, hilariously characterizing Desire as “like some small animal that only comes out at night.”

Sex and class converge in “I Spy”—a grandiose fantasy of Cocker as social saboteur whose covert (to the point of being unnoticed, perhaps existing only in his own head) campaign against the ruling classes involves literally sleeping with the enemy. “It’s not a case of woman v. man/It’s more a case of haves against haven’ts,” he offers, by way of explanation for one of his recent raids (“I’ve been sleeping with your wife for the past 16 weeks... Drinking your brandy/Messing up the bed that you chose together”). Looking back at Different Class many years later, Cocker recalled that in those days he thought “I was actually working undercover, trying to observe the world, taking notes for future reference, secretly subverting society.”

“I Spy” is probably the only song on Different Class that requires annotation, and even then, only barely. Crucial to Cocker’s democratic approach is that his lyrics are smart but accessible: He doesn’t go in for flowery or fussy wordplay, for poetically encrypted opacities posing as mystical depths. He belongs to that school of pop writing—which I find superior, by and large—where you say what you have to say as clearly and directly as possible. Not the lineage of Dylan/Costello/Stipe, in other words, but the tradition of Ray Davies, Ian Dury, the young Morrissey (as opposed to the willfully oblique later Morrissey).

Cocker’s songs on Different Class are such a rich text that you can go quite a long way into a review of the album before realizing you’ve barely mentioned how it sounds. Pulp aren’t an obviously innovative band, but on Different Class they almost never lapse into the overt retro-stylings of so many of their Britpop peers: Blur’s Kinks and new wave homages, Oasis’ flagrant Beatles-isms, Elastica’s Wire and Stranglers recycling. On Pulp’s ’90s records, there are usually a couple of examples of full-blown pastiche per album, like the Moroder-esque Eurodisco of “She’s a Lady” on His ‘N’ Hers. Here, “Disco 2000” bears an uncomfortable chorus resemblance to Laura Branigan’s “Gloria,” while “Live Bed Show” and “I Spy” hint at the Scott Walker admiration and aspiration that would blossom with We Love Life, which the venerable avant-balladeer produced.

Mostly though, it’s an original and ’90s-contemporary sound that Pulp work up on Different Class, characterized by a sort of shabby sumptuousness, a meagre maximalism. “Common People,” for instance, used all 48 studio tracks available, working in odd cheapo synth textures like the Stylophone and a last-minute overlay of acoustic guitar that, according to producer Chris Thomas, was “compressing so much, it just sunk it into the track.... glued the whole thing together. That was the whip on the horse that made it go”.

With Pulp touring and with new material out, a young and unexposed generation are discovering their work. They get to hear the band play songs from Different Class three decades after its release. A chart-topping, award-winning masterpiece from the group, 30th October will see new acclaim for Pulp’s fifth studio album. If Jarvis Cocker recently joked that the album’s title is relevant when we consider an anniversary reissue will unveil the album’s full glory and sonic brilliance, it also refers to its superiority compared to other albums that were released in 1995 – in one of music’s best years. Different Class has a very…

APT title!