FEATURE:

Humble Mumble

Outkast's Stankonia at Twenty-Five

__________

IN terms of deciding…

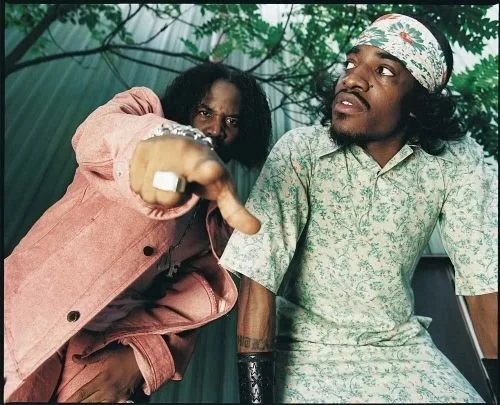

IN THIS PHOTO: Outkast’s Big Boi (Antwan Patton) and André 3000 (André Benjamin) in 2000/PHOTO CREDIT: GRIP Magazine

which album is the first real classic and work of genius of the twenty-first century, you could argue that Outkast’s Stankonia takes that honour. Released on 31st October, 2000, it is the fourth studio album from of Big Boi and André 3000. I think it is their best album. One of the best of all time, in fact. Because it turns twenty-five soon, I am exploring some features about the album. Notable and standout songs from Stankonia include Ms. Jackson, Humble Mumble, B.O.B. (Bombs Over Baghdad), and So Fresh, So Clean. Following 1998’s Aquemini, Outkast incorporated a broad array of styles into their next album, which included Funk, Rave, Gospel, and Rock within a Dirty South-oriented Hip-Hop context. This could have been a risk for a duo whose fans expected perhaps a certain sound. However, Stankonia was a massive success with fans and critics. Reaching number ten in the U.K. and two in their native U.S., many publications have included Stankonia in their best of lists. Also, this was an album that acknowledged Rave culture. Hip-Hop prior to 2000 was largely about slower beats. Outkast added something new and spliced the previously detached worlds of Rave and Hip-Hop. The songwriting throughout is commanding, fascinating and masterful. I want to start out by quoting a bit of FADER’s 2000 interview with Big Boi and André 3000:

“Stankonia is where they got they funk from.

But first, are you experienced? Uh, have you ever been... experienced? You, with your conscious rappers and Black Augusts? You, with your headwrap, and you, with your backpack? You, with your getting-it, and you with your 360 degrees of hip-hop? Have you ever been knock-kneed, mind-blown, zooted and looted, all funked up and no place to go?

The thing about Big Boi's house is that inside it he has a Boom Boom Room, and the thing about the Boom Boom Room is that there's a stage in the corner. The stage isn't big, maybe three feet by three feet, but the surface is mirrored and there's a pole in the middle that reaches to the ceiling.

In fact, the stage is so small that you really don’t notice it's there until one of the women gets off the couch and starts to dance around the pole. Except that it's not really dancing, just a repetitive slow-mo gyration suggesting ennui. No one's really watching her and she’s not dancing for anybody else, a caged bird needing no listener to sing its song.

On the other side of the Boom Boom Room, several more women languish on low-slung couches. They all have names in which Ys replace Is— Chyna and Kym. At the bar, more of OutKast's Earthtone crew— Slimm, C-Bone, DJ and Nathaniel are making headway on a gallon of Hennessy and more than a couple of blunts. Unmastered tracks from OutKast's upcoming album blast from the stereo system.

A lot of shit is talked in the Boom Boom Room, but most of the conversation remains unspoken. lt's like any foreign land in that way, men and women acting out roles that are diffcult to understand when observed from the straight world. The only thing to do is keep up, keep your eyes open, and try not to pass out in that chair in the kitchen.

Downstairs in the garage the photographer is still shooting in a race against sunrise.

"I do this all the time," says Big Boi, leaning up against his mint Cadillac. Shutter clicks. The car is a pale cheddar with purple iridescence, and there is pride in his voice when he calls it his Paddymelt. "Really, this what we doing tonight? I love this type of shit. Little get-togethers at the crib, with the fellas and some hoes. It's just fun, you know?"

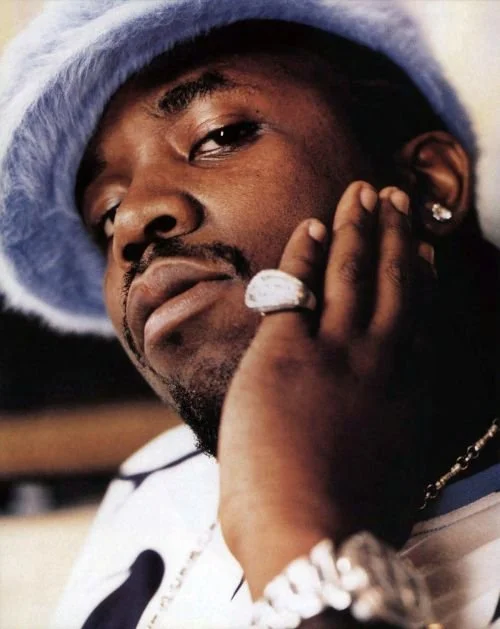

PHOTO CREDIT: Jonathan Mannion

At 4:37am a few of the women come down from the Boom Boom Room. In various stages of undress, they pose in and on the Paddymelt. "This is how we made the album," continues Big Boi. "While we were working on this album we would do this three or four nights a week. Every time we finished at the studio, we‘d head to the house. From four in the morning ’til two the next afternoon, just kickin‘ it."

Twelve hours earlier everything was understandable: OutKast, a new album, a photo shoot, an interview. In and out; no one gets hurt. But now the moment has taken on a timelessness, a surrealism that threatens to steal it all away to a land of no return.

Andre has fallen silent, leading only Big Boi holding the lifeline. "Stankonia is whatever's the funkiest shit ever," he explains, lucid. ’It could be that purple, or that funky-ass music."

And the photographer clicks away.

A RAINY NIGHT IN GEORGIA

It’s been storming for hours.

Andre is driving. But even as he watches the road and directs his Land Rover or whatever towards Big Boi's house in the woods, his eyes have turned inward and his mind has moved in another direction, past the other side of the game. This is when he conjures most the man from Electric Ladyland. More than the headband or the mixed metaphors of his clothing, its the occasional sad, faraway look in his eyes that reminds you of Hendrix, a sense of being young and world-weary at the same time.

"The funk is basically freedom," he says, not real heavy on it, just kind of think-ing aloud. "The funk is not a certain sound or a certain way you dress or a certain look. Something can sound funky or look funky, but my opinion of the funk is a certain freedom that started way back in Africa. But we don‘t want to make it no big racial issue or no shit like that."

That's because the Promised Land of Funk is an uncharted expanse of electro-magnetic technicolor modulations, and being Afrocentric alone might not qualify you for the trip. This probably explains why the roadside of such a pilgrimage is littered with DAT cassettes, gold records and backup bands with shallow pockets. Rhyming—or writing—about the funk without ever having gone there is pointless, like feeling the heat without complaining about the humidity.

"I guess we’re talking about an individual freedom," he says”.

I will end, like I have for several recent features, with a review from Pitchfork. I think their depth and analysis is particularly strong and interesting. However, first, this CLASH feature from 2020 marked twenty years of the masterpiece that is Stankonia. It was an album that won over people who were not fans of Hip-Hop. A varied album that still has not aged and throws up surprises, I remember it coming out in 2000. It was a big moment:

“The album was named after the recording studio that the duo bought in 1998. ‘Stankonia’ was a word that Andre created himself, and he explained that ‘Stankonia’ “is this place I imagined where you can open yourself up and be free to express anything”.

The album cover shows Andre standing shirtless facing forward, arms stretched outward and chin held high, along with Big Boi rocking a baggy t-shirt and big necklace. Both are placed in front of a huge drooped black and white American flag. The image is simple yet iconic, but gives little away as to how colourful the 24 track album really is.

The leading single 'B.O.B' exemplifies the album; it never sits still, unapologetically getting in your face with constant surprises. Bombs Over Baghdad remains calm for a maximum of five seconds, before a countdown from Andre 3000 sets off the fireworks. Both loud and lively, the song makes commentary of life in the ghetto, whilst referring to political turmoil in Iraq at around the same time. The duo's influence on the 90s rave culture can be heard through drum 'n' bass beats. The track is constantly switching, adding other layers.

With most OutKast songs, it's easy to tell who has had the most influence creating the track. Big Boi firmly stands at the front for 'We Luv Deez Hoez'. The sarcastic pimping song is both catchy and straight up gangster. Whilst ‘Stankonia (Stanklove)’ is all Andre 3000, he sings the hook, stretches his voice during the verses. The song is all harmony, with no rapping, providing more of an insight into what you would hear more of on their following album ‘Speakerboxx / The Love Below’.

The duo were now grown ups, and the subsequent problems they faced are referenced on the album. Standout track ‘Ms. Jackson’ is a prime example of this. Both radio friendly and catchy, the track pushed them into stardom, winning a Grammy and being the first of three songs to reach No.1 on the Billboard charts. If you hadn’t heard of OutKast before, you certainly would’ve by now.

Influenced by Andre and his relationship with Erykah Badu, ‘Ms. Jackson’ is the story of ruined relationships, and promises that weren’t kept. A storm is centred as the central theme through the music video and track, a metaphor for 'stormy' relationships, as Andre states: "Hope that we feel this, feel this way forever/You can plan a pretty picnic, but you can't predict the weather, Ms. Jackson".

‘Stankonia’ is a journey through sounds of funk and hip-hop, 'So Fresh, So Clean' is a straight up anthem, both catchy in the hook and beat. Then, there’s the turbulent ‘Toilet Tisha’, a vivid story from the hood of a 14-year old girl struggling with the idea of having a baby. 'Spaghetti-Junction' shows the duo's chemistry at its fullest. Each raps a verse before coming together on the last back-to-back, with their flows blending into each other. The opener ‘Gasoline Dreams’ has guitar strings that hit you like a truck and ‘Gangster Sh*t’ is an aggressive head bopper. In-between songs, skits lead onto tracks or are used for comedic effect in heavy Atlantian slang”.

There is another interesting article that I found from 2020. NPR. A fascinating interview and conversation between Dr. Regina Bradley (an award-winning writer and researcher of the Black American South), Gavin Godfrey (a freelance writer and editor from Atlanta, he’s written for CNN, Rolling Stone, Vice, FADER and COMPLEX) and Christina Lee (an award-winning storyteller whose writing, commentary, and production work appears in iHeartMedia, NPR, and more). They chatted about an album that “was a curation of not only OutKast's investment in the future, but a blueprint for what was to come later with Speakerboxxx/The Love Below: a look at the group's evolution as men and as artists, solidly and firmly centered in a stronghold of how the South could sound”:

“When OutKast released its fourth studio album Stankonia, the pioneering duo out of Atlanta, Ga., was not new to this, but they remained true to the hip-hop thing. Released on Halloween 2000, months after the initial Y2K scare that left people terrified of being throttled back into a period of darkness and technological paranoia, Stankonia took full advantage of the new millennium. They stayed true to what they did best and created something powerful on the fringes of mainstream pop culture's expectations of them as southerners and as rappers.

Breaking new ground cleared from the debris of nostalgia, burned with their Chonkyfire, Stankonia challenged listeners to reconsider what it meant to be OutKasted in the wilderness of an unknown new world. Never ones to shy away from the stank of imagined and social-historical realities, Stankonia is a demonstration of André Benjamin and Big Boi evolving their sound, their identities, and their art. Benjamin was blasting centuries ahead with his latest moniker, André 3000, an Afrofuturist prediction that the future was Black and dope as hell, and Big Boi was growing increasingly experimental in not only his lyrical delivery but his fashion sense, paralleling Benjamin's own eccentric flair for fashion.

Stankonia was a curation of not only OutKast's investment in the future, but a blueprint for what was to come later with Speakerboxxx/The Love Below: a look at the group's evolution as men and as artists, solidly and firmly centered in a stronghold of how the South could sound. Earthtone III — consisting of Benjamin, Big Boi, and DJ David "Mr. DJ" Sheats — are on full display for the majority of the album. Stankonia showcases influences from multiple genres, eras, feelings, and experiences, including EDM on the much celebrated and canonized "B.O.B."

Dr. Regina Bradley: I feel like I'm back in high school, junior year — shout out to Westover High School — running to lunch, listening to Stankonia. I'm really in my feelings. Chris, Gavin, what are your immediate reactions to listening to Stankonia 20 years later?

Gavin Godfrey: Man, it still sounds super fresh 20 years later. To me, not much has changed other than time. They still sound as fresh as they did 20 years ago.

Christina Lee: I mean, listening to this album kind of feels crazy. I sometimes forget just how vibrant this album is, how ambitious this album is, but that's what immediately strikes me. It's amazing how OutKast is able to really just branch off at this point, especially when you compare it to their previous discography.

What do you think it is about the Stankonia album that really made folks sit up and pay attention to what they were doing and why they couldn't just be considered Southern hip-hop after all?

Lee: I think what's really interesting about this album is that it is absolutely Southern hip-hop, but there is a part that is very conscious of the world around them. You're seeing these dichotomies play out, the sort of balance between mainstream hip-hop and the conscious hip-hop era. We have to remember that, at this particular time, those two genres are starting to branch off. And the thing is, Stankonia encompasses all that.

Godfrey: I think they built a world with this album. I'm gonna nerd out real hard real quick, but OutKast, for me, is almost like George Lucas when Star Wars was good. He was known for building whole worlds, but he literally was just telling stories about everyday occurrences. But he made you see it through this lens. OutKast is still very much rooted in Atlanta. Through the lyrics, through the sounds, they're not only thinking globally, but universally; these boys are thinking about the cosmos.

When I talk to DJ and Big Boi about this, the name Stankonia comes from Dre just always referring to everything they did as funky. They want everything to be funky, funky, funky and go back to the crazy lack of limitations that came from Parliament Funkadelic before them. I think it all stemmed from them being comfortable in their world, but also trying to step outside of their comfort zone and bring everybody along with them.

We're not just going to gush on Stankonia, you know, I got to ask you: What do you think has aged well about the album and what do you think hasn't aged so well?

Godfrey: In the culture now, I don't know how "Snappin' & Trappin'" would have been received, how much folks would have responded to what Killer Mike was saying in there. Back then, maybe lyrically, you could get away with a lot more because there wasn't the proliferation of social media, a constant influx of information to call out every single lyric, every little thing somebody did.

Listen to Stankonia now and it's wild, you know, because, man, these dudes knew. It's like they knew everything that was going to happen today. But they were talking about it 20 years ago and it's still so, so relevant. So, I mean, a lot has aged well for me in terms of I think it sounds even better now than it did then.

Lee: I mean, I echo absolutely everything that Gavin said. I think the thing with OutKast is that the perspective is always coming from, like, "Here we're going to give you some food for thought." And I think in this particular age, giving food for thought isn't clear cut enough for listeners. I think listeners expect groups to kind of take on a very particular stance. And maybe this is because I'm reading a book called The Butterfly Effect; it's the first biography of Kendrick Lamar by Marcus J. Moore. But in listening to some of Kendrick's discography and comparing it to Stankonia, I think I'm most struck by how, at this particular time, there's a lot of hip-hop acts that are turning to rock past and Black music past and understanding that even though we're operating within the space of hip-hop, we have the entire musical gamut to pull inspiration from”.

will move to Albumism and their twentieth anniversary feature about Outkast’s Stankonia. Each feature provides new details and focus. I really love this album twenty years later. One that is still influencing artists. An undeniable work of genius from a duo who are among the legends of Hip-Hop:

“Still, Stankonia is at its best when OutKast comes at the audience from unexpected angles. The quirky “I’ll Call Before I Come” is often an overlooked entry on the album, and one of my personal favorites. For a song about fucking, both members of the group are pretty gentlemanly, as André declares his preference for “old school, regular draws” and Big Boi states that a woman’s sexual satisfaction is of paramount importance. With Eco and Gangsta Boo appearing to detail their fantasies and desires, the song is also equal opportunity in its freakiness. I also love the instrumentation for the track, which sounds like it could have been lifted from a late era Sly Stone song or some late ’70s funk.

“Humble Mumble,” bizarre in its own right, is anchored by upbeat Caribbean-influenced grooves and unexpected beat shifts. In terms of subject matter, the track is all over the place, but still feels coherent. While Big Boi addresses coping with adversity in the pursuit of one’s goals, André ponders the complexities and contradictory nature of everything from hip-hop music to life itself. The song also features the vocal talents of Badu, who apparently was on good enough terms with André to contribute both the chorus and a melodic final verse to the song.

OutKast reach deep into their bag of way-out funk tracks as Stankonia draws to a close. First is “Toliet Tisha,” the sorrowful ballad of the late 14-year-old Tisha. Damn, we miss her. Musically, the song sounds lifted from a mid-1990s Prince album. Amongst layers of watery synths and guitars, André sings through heavy vocal distortion, voice nearly unrecognizable, and Big Boi delivers a harrowing spoken-word verse. Together, they narrate a tale of an unwanted teenage pregnancy, and the heartrending outcome. The song is legitimately sad but doesn’t wallow in tragedy for its own sake.

“Slum Beautiful” is another personal favorite on the album, a psychedelic dedication to their female companions. The song oozes cool, as André, Big Boi, and Goodie Mob’s Cee-Lo wax philosophic about the effects that the objects of their affection have on their mentalities. Back then, Cee-Lo could still be considered one of the best emcees around, and his vivid and awestruck verse is a highlight. The musical backdrop is a mix of Jimi Hendrix and Graham Central Station, as backward-masked guitars mix with a resonant bassline and complex percussion.

The album ends with the funk-drenched title track a.k.a. “Stank Love.” Clearly inspired by late ’70s/early ’80s P-Funk ballads, André and Sleepy Brown channel George Clinton and Garry Shider, inviting the objections of their affection to release their inhibitions and soar with the kites in the sky through their freaky love. The song is mostly instrumental, rattling with gurgling bass and keyboards, and ghostly voices wail. Big Rube delivers an appropriately way-out spoken word piece, speaking of an act of love so profound that it’s “engulfing, encompassing like a cataclysmic shockwave of an impact so deep, but not one of destruction, but of creation.” The song doesn’t so much as end as it fades out into the ether, remaining with the listeners as it echoes through the speakers.

In some ways, Stankonia is the “final” OutKast album, as the group followed it up with the Speakerboxxx/The Love Below project (2003), a combination of solo albums for each of the duo. They effectively broke up afterwards, only reuniting to release the 2006 Idlewild soundtrack, which was largely phoned in. Suffice to say that OutKast went out as a group on a high note here, having travelled just about everywhere there was to go, and treating their followers to a hell of a journey. People still clamor for another OutKast album, but I personally feel like they went out on top. Always leave them wanting more”.

I will wrap things up with Pitchfork’s 2018 review. They heralded Stankonia and how it is this “transcendental funk fantasia, an unequivocal commercial and artistic triumph”. I am curious how journalists will cover Stankonia on its twenty-five anniversary on 31st October. How it still changes and evolves Hip-Hop. How it broke barriers and was revolutionary:

“There is so much going across Stankonia—the coordinated confetti of noises on “Gangsta Shit,” the uneasy meditation of teen pregnancy that is “Toilet Tisha,” the playful lasciviousness of “I’ll Call Before I Come,” the melodic menace of “Red Velvet,” the skits that spoke in metaphors to the subconscious via hood tongues, the arrangements and progressions that felt capricious, but totally natural. The backing tracks weren’t soundscapes as much as they are aural murals graffitied on the cosmic underpasses where abandoned tricked-out space shuttles rest, stripped of their Brougham rims. It was music that was tangential to crunk, a predecessor to trap, indebted to hip-hop, electro, funk, rock, and anything alternative—the type of music that usually succeeds on intellectual levels and rewards nerds, but not readily equating to an album that would sell more than 4 million copies. Yet OutKast is probably best defined by defying parameters and expectations.

Stankonia is easily the group’s most expansive and abrasive effort. It’s more accomplished than their biggest seller, the double-disc Speakerboxxx/The Love Below, which lacks the tension and dichotomy of André and Big Boi locked in a studio, warring with each other and themselves to the extent that created numbers like “Humble Mumble,” Stankonia’s breakbeat-ish, Caribbean-tinged track where Big Boi admonishes a simp with “Sloppy slippin’ in your pimpin’, nigga/You either pistol whip the nigga or you choke the trigger,” before André recalls speaking with a rap critic: “She said she thought hip-hop was only guns and alcohol/I said ‘Oh, hell naw!’/But, yet, it's that too.”

OutKast had always consisted of a politically conscious pimp and a spiritual gangsta, but on Stankonia, those identities came to the fore with a greater distinction that paradoxically allowed them to sound closer together than they had since their inception—even as André sat out songs like “Snappin’ & Trappin’” and “We Luv Deez Hoez.” On Stankonia’s first proper song, “Gasoline Dreams” Big Boi raps about their clout and the limits thereof—“Officer, get off us, sir/Don’t make me call [my label boss] L.A. [Reid], he’ll having you walking, sir/A couple of months ago they gave OutKast the key to city/But I still gotta pay my taxes and they give us no pity”—while André throttles out a brainy hook: “Don’t everybody like the smell of gasoline?/Well burn, motherfucker, burn American dreams.”

Stankonia is an album about many things and full of epigrams; so ahead of the curve that one of its many double entendres—“I got a stick and want your automatic”—is now a bona fide triple entendre. It’s about sounds as smells and music as sex, but mostly it’s about two black kids from Southwest Atlanta, boogieing with chips on their shoulders, making Molotov cocktails of songs that sound like a revolution’s afterparty. It’s peppered with personal narratives and small slips of autobiography, and it tackles big ideas both directly and obliquely. But, ultimately, it sounds like two artists going pop on their own terms while trying to make sense of, and change, the world around them. Closing in on two decades after its release, Stankonia remains loud as bombs over Baghdad and humble as a mumble in the jungle”.

Without doubt one of my favourite albums ever, I think back fondly to 2000 and the release of Stankonia. Big Boi and André 3000 were in perfect harmony on this album! Rather than repeating what they had done before, they pushed their vision and sound out. Bringing in different genres and directions, it all blended perfectly into this masterpiece. One that continues to stun me. It is an album hard to top…

AFTER quarter of a century.