FEATURE:

At the Chime of a City Clock

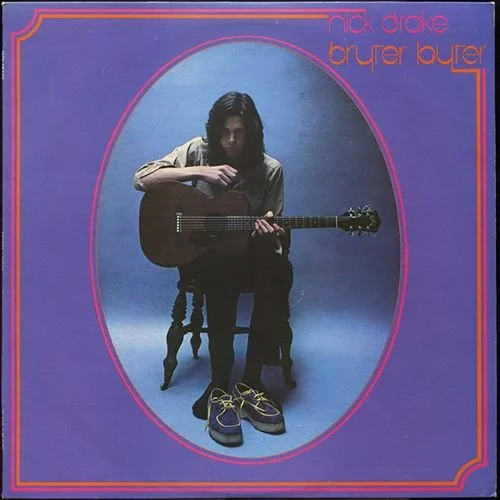

Nick Drake's Bryter Layter at Fifty-Five

__________

ONE of the most beautiful…

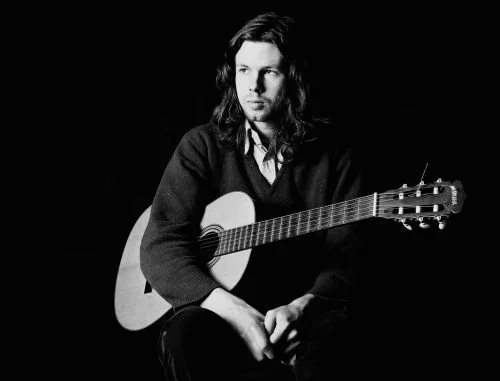

IN THIS PHOTO: Nick Drake in 1971/PHOTO CREDIT: Tony Evans/Timelapse Library Ltd/Getty Images (via The Guardian)

albums ever turns fifty-five on 5th March. Bryter Layter was the second studio album from Nick Drake. I don’t think it gets as much attention as his debut, Five Leaves Left, or his third (and final) album, Pink Moon. The latter album was Drake unaccompanied and it was this more sparse and stripped work. Like Five Leaves Left, Bryter Layter is different in terms of its sound. String and brass arrangements. Flute, saxophone, celeste and harpsichord are among the instruments that help score these wonderful songs. Perhaps best known for tracks like Northern Sky and Poor Boy, I feel every track on the album is a work of wonder. At the Chime of a City Clock and Hazey Jane I are among my favourites. I do want to get to some reviews of Bryter Layter. I am not sure how many people will mark its fifty-fifth anniversary. It is a pity, as this is a really remarkable artist whose career was short but remains hugely influential. In terms of musicians who have been affected by Nick Drake. In 2000, Q placed Bryter Layter at number twenty-three in its list of the 100 Greatest British Albums Ever. I want to start out with Golden Plec and their assessment and reflection on 1971’s Bryter Layter. Reappraising this masterpiece in 2016 – forty-five years after its release -, I would like to feel people will write new words about Bryter Layter close to 5th March:

“Cambridge, 1969. Cyclists throng the roads, college scarves flying; the bells of Great St. Mary’s clang out, whilst the River Cam meanders slowly by. Nick Drake is submerged in all of this, ostensibly studying for a degree in English literature. A product of colonial Britain (he lived in Burma as a child), public schooling, and now the stifling traditions of Oxbridge, Drake finds release in the dual pleasures of guitar and smoke - his debut album, ‘Five Leaves Left’, is named after the preemptive warning near the end of a Rizla packet. After playing a supporting slot at the Camden Roundhouse, he strolls into a record deal and accordingly strolls out of Cambridge, though the influence of that city remains plain to hear in his music.

At the time, East Anglia was a haven for aspiring troubadours. The annual Cambridge Folk Festival was inaugurated in 1965, welcoming acts including Pentangle, Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick. Pink Floyd’s 1969 album ‘Ummagumma’ included a seven minute paean to Grantchester Meadows, an area of pastureland just south of the city. Likewise, Nick Drake’s music is shaped by the topography of bleak fenland, river weed and fresh ploughed fields. He sings of the River Man, fallen leaves, the day dawning from the ground - depicting the English countryside through chords alone. Unfortunately for Drake, what is popular in rural England is not necessarily popular elsewhere - and so to 1971, ‘Bryter Layter’, and the ensuing tensions between musical self expression and thirst for public acclaim.

Put simply, ‘Bryter Layter’ is a beautiful album. It is suffused with warmth, excitement, a sense of promise. It’s the early 1970s, London’s calling: Nick Drake has escaped the rigours of academia for a leafy suburb of Camden Town, and his sense of optimism is palpable.

The opening track, instrumental Introduction, evokes the smell of cut grass warmed by slightly tipsy afternoon sun, its lush string arrangements drawn out over rippling fretwork. Everything speaks of a bright future - as Drake insists in Hazey Jane II, “Now that you’re lifting/ Your feet from the ground/ Weigh up your anchor/ And never look round”, upbeat lyrics leaping effortlessly over bobbing bassline and offbeat horns. You get the sense that he is perfectly happy making music purely for his own enjoyment, relishing the collaboration with folk luminaries such as Fairport Convention’s Dave Mattacks and Dave Pegg, and John Cale, formerly of The Velvet Underground, all of whom feature on the record.

In truth, the ‘green and pleasant’ vision of England and its music was fading fast. By 1971, Drake sat slightly uncomfortably between Haight-Ashbury psychedelia, and the slow onslaught of prog and folk rock. The Rolling Stones’ ‘Sticky Fingers’, was released a month after ‘Bryter Layter’, and the dropped T, working class vibe of Jagger and Richards resonated with the public far more than the middle class accent of a sensitive songster could. Despite the defiance of Hazey Jane I (“Try to be true/ Even if it’s only in your hazey way”), the cold hard facts of album sales were hard to ignore. Though ‘Bryter Layter’ was a critical success, Drake’s aversion to performing, compounded by worsening depression, saw him refuse to tour the album. It sold fewer than 5000 copies.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing. Listening to ‘Bryter Layter’ 45 years after its release, it is possible to take the album entirely out of context and treat it as a stand alone work - an atmospheric blend of metaphysical lyrics, quasi-orchestral arrangement and virtuosic guitar.

Indeed it’s arguably more relevant today than it was back then - in this era of instant celebrity and stifling PR, the underlying bitterness of songs dealing candidly with fame, or the lack of it, is particularly pertinent. And of course the tragic circumstances of Drake’s suicide at the age of 26 colour modern perceptions of his work, and interpretation of his lyrics. But whether ‘Bryter Layter’ is a product of its time, or a product of its legacy, it is an album well deserving of its cult status. Time to dust off that vinyl - and let Nick Drake brighten your Northern Sky”.

I will end with a review of Bryter Layter from Rolling Stone. Next, I am going to come to Klof Mag and their take on Bryter Layter. Reviewing it in 2021, they write how the album offers these magical qualities. Something that is there “to allow us to glimpse the fleeting intangible parts of us, act as a vessel to this visceral realm – forever slipping through our fingers in the vice-like grip of the modern world”. Critics in 1971 were not fond of an album they felt was boring and did not like the tone and timbre of Nick Drake’s voice. The fact he did not tour the album didn’t help. However, Bryter Layter is more influential today than it ever was, so it is getting overdue affection:

“Folk music was at the heart of the tumultuous late 60s and early 70s: troubadours created elaborate progressive folk; Al Stewart and Roy Harper employed diverse instrumentation; explorative basslines became ever more common; John Martyn and the Pentangle fused jazz rhythms and harmonies into hardwired folk, whilst Fairport convention produced angular, electric albums. Drake’s producer Joe Boyd was notably present, signing the prolific Incredible String Band, who along with the likes of the Third Ear Band and Quintessence developed another 70s folk direction. It was in this world of experimentation and musical fervency that Nick Drake recorded Bryter Layter.

Drake’s producers, friends and labelmates pushed at the forefront of experimentation as his iconic sound matured. But it’s easy to see him as apart or distant from this world. Even on the cover of Bryter Layter, his most collaborative work, he’s shrouded in shadow – a promise of the quiet, dark place we enter through his songs. Drake was described by his close, protective friend John Martyn as the most withdrawn person he’d ever met, whilst Nick’s long-time producers Wood and Boyd recall his hesitation to stamp his authority when recording ‘Five Leaves Left’ and his despondent frailty in the ‘Pink Moon’ sessions. Bryter Layter, however, is distinct, and with the benefit of distance that time provides, it is, I think, Drake at his most ambitious and coherent – proactively responding to the vibrant musical world around him.

A clear example of Drake’s control and steel-mindedness on Bryter Layter can be seen in his choice of musicians. Even against the influential personalities of his producers, Drake was driven by his own vision, dismissing their string arrangements. As Wood told Arthur Lubow, ‘He said he’d got his friend, Robert Kirby, who had never done anything in a recording studio.’

This personal stamp of decision making is seen as the album opens. Drake’s overture, the first of three instrumentals Nick insisted on against Boyd’s wishes, features lilting, delicate guitar swirls throughout – drawing attention among the sombre sweep of Kirby’s strings. It’s gentle crafting of a mournful yet playful veil of sound hints at mortality and loss as it scatters around. Hazey Jane II whisks the veil back into the air, lacing it with layers of Richard Thompson’s intricate guitar. A rhythmic skip is provided by Dave Mattack and Dave Pegg, also of Fairport Convention, who appear throughout the record, enriching the albums rhythm section with the dulcet backbeat of their well-honed dialogue, evidence of Drake’s relish of the ever-expanding folk pallet. Drake later delves into what were prominent contemporary tropes (perhaps dating the album somewhat for the modern listener), with the use of Lyn Dobson’s flute on the title track and John Cale’s viola, celeste and harpsichord contributions to sprawling folk jams, Fly and Northern Sky.

Drake was an admirer of the Beach Boys, and drummer Mike Kowalski brings a crucial element to Bryter Layter, his contributions offering poignant moments of fragility. Poor boy offers another twist and change of pace; uneasiness subtly imbued with the offbeat stabs of Drake’s guitar, referencing the 60s New York jazz of Jimmy Smith. Accompanying this is a deftly frantic drumming and gospel undertow bolstered by melodic Bossa Nova phrasing. Tension heightens as Drake floats ‘where will I stay tonight,’ leading into the rhythmic solo of Chris McGregor, a force in both jazz and African music, bringing with him echoes of the harmonic inventiveness of McCoy Tyner shimmying through the piano.

The veil sweetly draped from note one remains throughout, as hints of Dylan and Van Morrison’s lilting, ethereal lyrical influences adorn the album in half-rhymes. Other American influences can perhaps be seen in some of Drake’s guitar work, the sparser arpeggiated moments, often indulged with chromatic changes and major to minor shifts, such as in One of These Things First, evoking the American musicians he became enamoured with: Peter, Paul and Mary, Joni Mitchell on Song to a Seagull, and the older folk masters such as Josh White.

This is an album brimming with influences, stripped down and reeled together in a sequence of dreams, helping Bryter Layter stand out not just among Drake’s haunting discography, but against the whole era. It is an album of contemporary decision, led by Drake.

Conversely, Drake was rarely cited as an influence in his time, adding all the more fuel to his image of doomed inertia. However, the closing song on the album, Sunday bears a startling resemblance to Bowie’s Kooks released the following year, perhaps the first of many debtors – an impact unknown by Drake himself”.

I am ending with a 1977 review from Rolling Stone. They wrote about this majestic album that contains “enchanting melodies, stirring empathy, and authenticity”. You can argue which of Nick Drake’s three albums is his finest moment. I feel Bryter Layter is his most underappreciated, so I was keen to spotlight it ahead of its fifty-fifth anniversary:

“Nick Drake may be the most ethereal recording artist I’ve ever heard. His fleeting career — the moody, mysterious music, the remote relationship with his record company — seemed calculated to distance him from reality. Yet his hushed songs touch a rare tranquillity that approaches poetry, and when he died in 1974 at the age of 26, he left behind three albums which are gradually making him a posthumous legend. Bryter Layter is the second of these LPs to be rereleased by Island Records through its remarkable budget label, Antilles.

Drake’s melodies are seldom less than enchanting. Built around acoustic folk-jazz guitar figures and muffled percussion, they become emotionally charged when shaded by arranger Robert Kirby’s poignant, eddying strings. Drake’s impressionistic lyrics are vivid but provocatively sketchy, making them as curiously personal as phrases mumbled in sleep. They’re delivered in an airy, nearly unconscious whisper that blends as naturally into the arrangements as a breeze rippling through tall grass.

Compared to the gloomy, vinegary, autumnal Five Leaves Left and the reportedly stark Pink Moon, Drake’s second album is a relatively pleasant collection. “Bryter Layter” and “Sunday” are light, carefree flute instrumental, and the cantering “Hazey Jane II” is positively brisk (though qualified by some disturbing lyrics). “Northern Sky” gently details how a loved one has enhanced his appreciation of life.

Even in his best moods, though, Drake seems to be reaching out from a position of isolation to a like soul, as in “Hazey Jane I”: “Do you feel like a remnant of something that’s past?” More characteristic is the intensely considered solitude of “Poor Boy,” “One of These Things First,” (a light waltz about possibilities dismissed) and “Fly,” which features John Cale’s moaning viola.

Whether obscurely introspective or groping outward, Drake seems to be communing with a pantheistic spirit; he consistently charts this communion with stirring empathy and authenticity — but not clarity. It’s a measure of his instinct for maintaining a sense of mystery that Bryter Layter’s reflections are as ephemeral as a man’s breath on a mirror”.

Nick Drake would follow Bryter Layter a year later with Pink Moon. He sadly died on 25th November, 1974 at the age of twenty-six. One of these artists you wonder where he could have headed had he lived. However, Drake left behind these wonderful and transcendent albums. Bryter Layter among the most beautiful albums ever recorded. One that people should listen to ahead of 5th March. If this is an album that you have not heard in a while (or ever), then do make sure that you…

PLAY it now.