FEATURE:

Needle Drops and Scores to Settle

Scene Seven: The truth, no matter what it is, isn’t that frightening: Drive My Car (2021)

__________

THE second time…

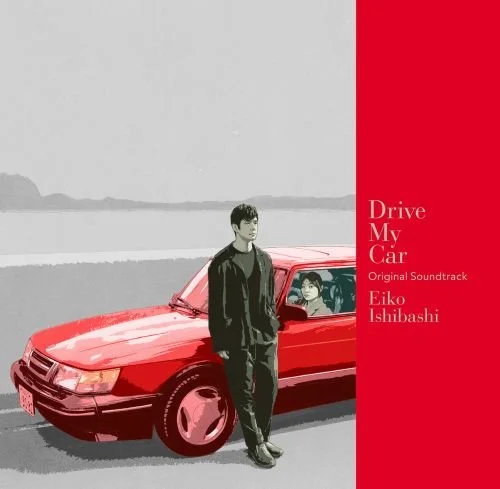

IN THIS PHOTO: Eiko Ishibashi/PHOTO CREDIT: Bas Bogaerts

I am spotlighting a film score rather than a soundtrack, this is also the most recent inclusion, year-wise. Eiko Ishibashi’s amazing score for Drive My Car. I will come to some reviews of the score and an interview with its composer. I am starting out The Guardian and their review of a marvellous 2021 film. An adaptation of a Haruki Murakami work (Drive My Car is a celebrated short story by Murakami, featured in his 2014 collection, Men Without Women, which explores themes of grief, connection, and loneliness through a widowed actor who hires a young female chauffeur), this film might have fallen under the radar, as the pandemic meant that people could not get to the cinema as much as they would have liked:

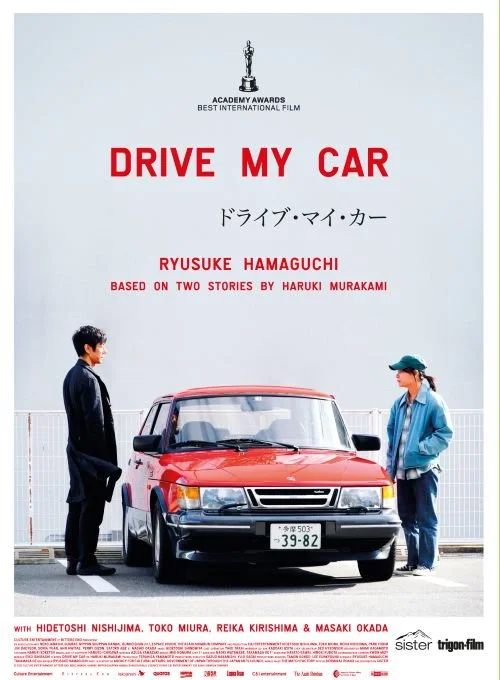

“Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s mysterious and beautiful new film is inspired by Haruki Murakami’s short story of the same name – and that title, like Murakami’s Norwegian Wood, is designed to tease us with the shiny wistfulness of a Beatles lyric. Hamaguchi’s previous pictures Asako I and II and Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy were about the enigma of identity, the theatrical role play involved in all social interaction and the erotic rapture of intimacy. Drive My Car is about all this and more; where once Hamaguchi’s film-making language had seemed to me at the level of jeu d’esprit, now it ascends to something with passion and even a kind of grandeur. It is a film about the link between confession, creativity and sexuality and the unending mystery of other people’s lives and secrets.

Yûsuke (Hidetoshi Nishijima) is a successful actor and theatre director who specialises in experimental multilingual productions with surtitles – he is currently working on Beckett’s Waiting for Godot and is preparing to play the lead in Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. He has a complex relationship with his wife Oto (Reika Kirishima), a successful writer and TV dramatist who has a habit of murmuring aloud ideas for erotic short stories, trance-like, while she is astride Yûsuke having sex, including a potent vignette about a teenage girl who breaks into the house of the boy with whom she is obsessed.

The couple learn that Yûsuke is in danger of losing the sight in one eye – he later learns with a shock that this has changed the short story that she was working on – but this perhaps makes it easier for him to accept that he will need a driver for his trusty Saab 900 when he later directs a new revival of his Vanya production at an arts festival in Hiroshima, a city that is photographed with crisp unsentimentality. Things are complicated by a devastating event in Oto’s life, and Yûsuke being confronted with proof that she had been having an affair with a handsome and disreputable young actor and celebrity called Kôji (Masaki Okada). For complex reasons, he casts this same bumptious Kôji in the lead role for Vanya for his revival, assuring the actor calmly that makeup will cover the age difference, and responds readily but with cool reserve when Kôji keeps saying he wants to talk to him over a drink after rehearsals. This strange duel between the two men is happening alongside Yûsuke’s growing relationship with his driver Misaki (Tôko Miura) whose professional reticence evolves into something else when he starts confessing his anguish to her – prompted by the fact that he likes to play a certain cassette in the car: the voice of his wife running his lines for Vanya.

As Yûsuke, Nishijima has a certain severity, inscrutability and the almost martial self-discipline of someone who is accustomed to leadership and to giving orders to actors while seeming open to their suggestions. (Oddly, when he is in makeup for Vanya, he reminded me of Yasujirō Ozu’s veteran player Chishû Ryû.) Miura’s performance has a reserve of its own, as his confessor and fellow smoker. Chekhov’s play, with all its desperation and regret for missed life chances, has become a touchstone for Yûsuke, and almost a separate character in the movie. What if … Kôji was playing Vanya, not him? What if Kôji was his wife’s partner, not him? What if he had been able to master his feelings, swallow his pride and actively confront his wife with what he knew about her secret erotic life and how much he had been hurt by it? Would this blaze of attempted honesty have saved their relationship? Or destroyed it?

And all the time, Misaki is growing in importance, and in the film’s extraordinary final section, her story is told; a story that need not thematically dovetail with everything that has gone before, other than to show us once again, that other people’s lives are complicated and withheld, and that we are being arrogant if we think that we know everything there is to know about the people that we meet.

Drive My Car is an expansion of a short story, and perhaps it’s true to say that Hamaguchi’s storytelling aesthetic here, as in his other films, is a mosaic or choreography of short stories, an archipelago of lives. Yûsuke, Oto, Kôji and Misaki are living their own stories, and the drama superimposes and overlaps them like a Venn diagram. And there is something very moving when we close in on one particular tale, one life. It is an engrossing and exalting experience”.

Eiko Ishibashi is a composer that is quite new to me. Her score for Drive My Car is extraordinary. I was completely immersed and engrossed when I heard the album. I wanted to discover more about a score for one of the best films of 2021. In celebrating modern-day great composers, women are often overlooked. It is important that composers like Eiko Ishibashi are celebrated and spotlighted more. In 2022, when the soundtrack/score was reworked for the EFG London Jazz festival at Kings Place, London (The Guardian provided their take), Variety spoke with Eiko Ishibashi about crafting and creating Drive My Car’s emotional and stunning score:

“Enter Eiko Ishibashi, an experimental Japanese multi-instrumentalist whose 2018 “The Dream My Bones Dream” was a turning point in an already decade-long career of scores for theater and short films.

Ishibashi’s 2018 album of haunting soundscapes and its electro-acoustic mix of noise, oddball pop, improvisational jazz and minimalist, modern classical music made her a cinematic force equal to Hamaguchi. The more textural and sweeping aspects of Ishibashi’s bittersweet melodies were an elegant match for Hamaguchi’s vision.

After being known for crafting blunt, short films since 2001, Japanese director Hamaguchi’s romantic “Asako I & II” of 2018 signaled an aesthetic shift, a turn toward sweeping narratives with shadowy, but tactile, atmospheres. Such expanse was necessary for 2021’s “Drive My Car,” a tale of a theater director reckoning with the finality of death while working on a stage production of “Uncle Vanya” during long car rides.

To that end, Ishibashi’s contemplative song-score for “Drive My Car,” re-released in February on major streaming services with bonus tracks, is as distant and off-putting as it is intimate and readily engaging.

“Typically, I don’t use a lot of music in my films, but hearing the music Ishibashi made was the first time I thought ‘this could work for the film,’” says director Hamaguchi, who was introduced to her music by “Drive My Car” producer Teruhisa Yamamoto as filming was set to commence. “Hearing her work, I was struck by how wonderful her talent and technique was. It reminded me of a band I enjoyed in my 20s, Tortoise. It had a similar feel that really matched with my taste, so I was very happy to work with Eiko.”

The director says he and Ishibashi share similar backgrounds, generationally, as well as a shared career trajectory. “I think that comes from listening to the same things around the same time. We also share similar tastes in film. She watches a lot of movies and loves John Cassavetes, Douglas Sirk, Rainer Werner Fassbinder and all these filmmakers who I really enjoy. Our film language was very similar.”

Hamaguchi and Ishibashi both agree that making the music of “Drive My Car” in spurts — before and after the pandemic shutdown, as well as during the shoot itself — was a huge help in making her compositions for his cinematic vision their own living, breathing entity.

“Working on it step-by-step with director Hamaguchi while he was filming was very gratifying for me,” says Ishibashi.

The director continues: “We shot the first 40 minutes of ‘Drive My Car’ in its first chunk, around mid-2020, but had to stop because of COVID. We had Ishibashi work on that chunk first — she would send us motifs of different moments, and we would add those pieces into the edit as we went. That process of combining the edit and the music worked really well. Based on those motifs she came up with, I would give notes and she would record a final version after more back-and-forth. It wasn’t this abstract way of communicating an idea of what I wanted … it was visual to begin with. That went very smoothly and I will use that way of working with a composer in the future”.

I will end with a Pitchfork review for a mesmeric score. One of the best of the past decade. Before that, The Guardian spoke with a composer whose amazing score helped Drive My Car to Oscar success (it won the award for Best International Feature Film). Not a one-off, “the Japanese musician has reunited with its director for a collaboration unlike any other”. Her latest work was an E.P. released last year that was a collaboration with Jim O’Rourke. Pareiodlia is a stunning work. This is an astonishing composer who summons something dark, eerie and strangely beautiful. Such evocative and image-provoking music, Drive My Car is perhaps more graceful, romantic and tender. Though it does have these turns and unexpected sonic moments:

“Whether it’s Hitchcock and Herrmann, Spielberg and Williams or latterly Villeneuve and Zimmer, film directors often get into a glorious feedback loop with a preferred composer – and the latest is a burgeoning collaboration between Ryûsuke Hamaguchi and Eiko Ishibashi. Her jazz-pop theme for Drive My Car in 2021 was an instant classic – wistful, generous of spirit, even a little Gallic with its touch of accordion – and her score helped to carry the Japanese film to glory at Cannes and beyond, including a best picture nomination and best international feature film award at the Oscars in 2022.

“There was a big awards rush, festivals, and I think Hamaguchi was ultimately quite fatigued from the whole experience,” Ishibashi says, elegantly wrapped up in her cold-looking recording studio in the Yatsugatake mountains west of Tokyo, speaking via interpeter over a video call. “So I think he wanted to do something that was more experimental next. And myself, I’m interested in experimenting with what kinds of work I can do along with images.”

The result is a pair of astonishing new films in which the bond between director and composer is even more tightly fused: the drama Evil Does Not Exist and a short film, Gift, which is silent and designed to be paired with live performance by Ishibashi. Hamaguchi has described the two films, which use different takes, shots and narrative details from the same shoot, as a “small multiverse”.

Gift was the initial idea, after Ishibashi asked Hamaguchi for concert visuals and sent him demo pieces for inspiration. Hamaguchi went big, travelling to film near where Ishibashi lives, and even developing a script that wouldn’t be heard but would guide the actors in the silent film. “Hearing them on set saying these lines, he realised they had wonderful voices; the acting was wonderful,” Ishibashi explains.

So Hamaguchi expanded the film on the fly to make Evil Does Not Exist, a parable about the schism between urban and rural, between capitalism and its muffled opposite, as a glamping company arrogantly rocks up with plans to site a development in a peaceful village. The camera lovingly and languorously settles on feathers, leaves and brooks, and Ishibashi’s music is often beautiful to match. But violence and discord throb in the film’s bones, from the faraway gunshots of deer hunters to the way Hamaguchi will suddenly cut an Ishibashi piece down in its prime, leaving sudden silence.

“I felt an anger that I hadn’t felt in his past films,” she says. “Anger that felt directed towards the way humans work, the unfairness of this whole world.” Watching the raw footage, she says she drew on that feeling to create the film’s central musical theme: long, gorgeous overlapping chords for strings that take left turns into darkness.

In the past decade, three superb albums – Imitation of Life, Car and Freezer, and The Dreams My Bones Dream – were released by US label Drag City, and made her better known to American and European audiences. The latter is a reflection on Manchuria, an area of China named by its colonising Japanese forces – her late father was once based with the military there. Once again, it’s beautiful music laced with disquiet.

“My father carried a lot of scars from the war, but he never talked about his experiences,” Ishibashi says. “That led me to want to learn the history between Manchuria and Japan; the genocides that happened there. I realised there’s very little writing around this, and that led me to think about how perhaps victims can’t necessarily talk about it.

“There is a sense of Japan tending to close off from things that have happened – perhaps it has something to do with the fact that it’s an island country. It tends to also hide away certain facts and history, and carry on as if nothing had happened. In textbooks we don’t learn about Japan and its history as an oppressor, a coloniser, especially after the first world war. There’s a sense that it’s OK to not be learning about these things”.

I want to wrap things up with a review for the Drive My Car score. Reviewing it in 2022, Pitchfork lauded an album that “possesses a cool remove, mirroring the film’s glacial profundity with organic nuance and contemplative improvisation”. In terms of the versions and date order, initial formats like C.D. and cassette appearing in late-2021 in Japan, followed by wider digital/streaming release and vinyl in early-2022. That is why I have listed the release date as 2021, as that is when it first came out:

“Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car is a staggering exploration of grief, betrayal, and acceptance. The loose adaptation of a Haruki Murakami short-story follows Yusuke Kafuku (Hidetoshi Nishijima), a stage actor and director, as he mourns the deaths of his young daughter and his screenwriter wife, Oto (Reika Kirishima). Two years after Oto’s death, Yusuke relocates to Hiroshima where he will direct a production of Anton Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya.” Upon arrival, he is assigned a quiet female driver named Misaki (Toko Miura). Throughout many long drives in Yusuke’s vintage Red Saab, the two gradually open up about their individual sorrow.

Now nominated for four Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best International Film, Drive My Car is a profound masterpiece made all the more entrancing by its score, written by Eiko Ishibashi. The Japanese multi-instrumentalist and composer is best known for her experimental solo work, which ranges from jazz fusion to the imaginative dream pop heard on a recent tribute to a Law & Order character. Like the film’s protagonist, Ishibashi’s score possesses a cool remove and, alongside an ensemble that includes her frequent collaborator Jim O’Rourke, Ishibashi creates a soundtrack that is as moving as the film itself.

Bottom of Form

In the film, Yusuke’s theatrical method requires his cast to internalize the play’s text by running through the script without emotion before they are allowed to begin acting. (Yusuke rehearses his own lines by driving in his car and listening to cassettes of Oto reciting the other characters’ dialogue.) This emphasis on close listening and organic nuance is reflected in Ishibashi’s score, which is structured around variations of two themes, “Drive My Car” and “We’ll Live Through the Long, Long Days, and Through the Long Nights.” The eponymous core theme is set in motion by an opening burst of percussion and tumbling keys imbued with a certain thoughtfulness. This soon evolves into an upbeat and idyllic melody featuring yearning strings and the synthetic squawk of a melodion. However, this whimsical track is not the first piece of music heard by the audience. That would be “We’ll Live Through the Long, Long Days… (Oto),” a ghostly ambient track that abandons the score’s melodicism in favor of stillness, the falling of rain, and the muffled whooshing of passing cars.

In the same way that Yusuke suggests that a good driver allows their passenger to relax, Ishibashi’s score, even removed from the context of the film, allows the listener to sit back and enjoy the ride. Some of Ishibashi’s contributions suggest the transportive effect of driving in a concrete way. “Drive My Car (Cassette)” opens with a tape being inserted in a deck and the sounds of ambient traffic before it drifts into a pensive piano reverie. Meanwhile, Yusuke’s theme, “Drive My Car (Kafuku),” opens with the squeak of a seat being lowered before spiraling into rumination. “Drive My Car (Misaki)” also begins with an automobile sound as the titular character opens the Saab’s creaky front door and turns on the Saab’s ignition. This interpretation of the theme incorporates tumbling piano notes, brushed drums, and the steady thump of an electric bass; that such a reserved character is bestowed a warm theme underlines the idea that her wall of ice will someday melt, given the correct conditions.

Drive My Car’s second theme, “We’ll Live Through the Long, Long Days, and Through the Long Nights,” is more contemplative than its companion. There is an initial melancholy inflicted by strings so sorrowful that each note wavers like a dying breath. The “... (Saab 900)” version of the theme is the closest the score gets to a car crash: Percussionist Tatsuhisa Yamamoto’s fast and furious playing is layered atop the original theme’s piano melody with interjections of droning electric guitar and crashing cymbals. The arrangement is dusted, again, by vehicular ambience: the beep of a locked car, the slam of a door, and the click of a seatbelt. If the score’s other tracks capture a character or existential statement, “... (Saab 900)” is the titular car’s inner monologue as it drifts, and at one point, narrowly avoids getting side-swiped. “…(And When Our Last Hour Comes We’ll Go Quietly),” whose title is pulled from a soliloquy that arrives at the end of “Uncle Vanya,” features guitar work from O’Rourke that changes lanes from downcast meditation to hypnotic climax smoothly, as if there’s not a single bump in the road. And in its last moments, after a few final piano notes, Ishibashi’s glorious Drive My Car score goes quiet”.

You can find the Drive My Car soundtrack/score on Bandcamp. Even though it was released over four years ago now, I listen to it now and it moves me. If you can see the film it scores, I would recommend it. It is a beautiful award-winning and acclaimed film. The score adds these layers and emotions to the scenes. One of the most powerful pairings of music and visuals in recent cinema. That is why I wanted to highlight this masterpiece…

FROM Eiko Ishibashi.