FEATURE:

Beneath the Sleeve

Hole – Live Through This

__________

THE second studio album…

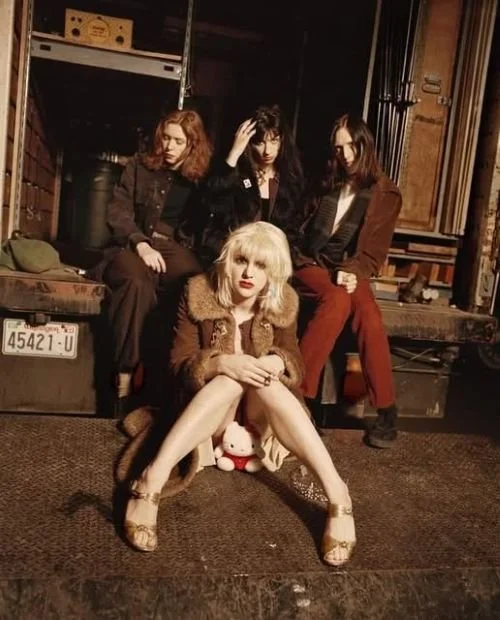

IN THIS PHOTO: Hole shot by Jeffrey Thurnher for SPIN in May 1994.

from the incredible Hole, Live Through This was released on 12th April, 1994. Perhaps more melodic, structured and less harsh than their 1991 debut, Pretty on the Inside, lead Courtney Love wanted to shock people who though the Californian band had no softer edge. Certified platinum in the U.S. in 1995, Live Through This was a massive critical and commercial success. I think Live Through This is Hole’s best album. Songs like Violet, Miss World and Doll Parts. Such a consistently brilliant album. With the majority of songs written by Courtney Love and Hole guitarist Eric Erlandson, Live Through This is considered a modern classic. It has featured high in lists of the best albums of all time. I am going to start out with an interview originally published by SPIN in April 1994 with Courtney Love. I am not bringing the entire thing in, though there are parts that I was interested in highlighting:

“Let’s get this out of the way. When Love talks about husband Kurt Cobain, which she does with some frequency, it’s with affection and slight amusement. Mostly he shows up in benign little anecdotes. Like how she keeps finding him dolled up in women’s sweaters from the ’50s. Or how, at her urging, he recently agreed to buy them a Lexus. But, after one relatively brief spin around town, and the catcalls of virtually all of their old friends, Cobain insisted they take it back. So they did. Now, they’re back to his scuzzy old Valiant. If you only knew Cobain by Love’s descriptions, you’d think he was an adorable, antic-prone young lug, more Ozzie Nelson than Ozzy Osbourne. And maybe that’s exactly who he is. Point is, her love for him, and for their daughter Frances Bean, is obvious.

I’d been forewarned by Geffen’s publicist, by friends of hers, even by the rest of Hole, that Courtney Love doesn’t trust journalists. Not since Vanity Fair‘s Lynn Hirschberg, whose infamous 1992 profile portrayed Love as little more than Cobain’s heroin-addicted, gold-digging girlfriend. The article contained a particularly scandalous quote, attributed to a “business associate.” “Courtney was pregnant and she was shooting up,” it said. What followed was an approximately yearlong trashing of the couple, chronicled rather exhaustively in Michael Azerrad’s Nirvana bio, Come As You Are.

“Yeah, Lynn,” Love sighs when the subject is broached. “I did a little private investigating on her, you know, and she has no friends. None. None!” For the next, oh, 40 minutes or so, Love’s conversation keeps veering back to Hirschberg, usually with disclaimers. As much as she may wish Hirschberg dead, Love admits she continues to read Vanity Fair. “Shit,” she says at the end of one particularly lengthy diatribe. “Why can’t I just fucking shut up about the bitch? Okay, that’s it. Zip.” She raises one hand and makes a slash across her lips. (When asked to comment, Hirschberg laughed and said, “I thought Courtney was my friend.”)

So what about the actual charges? “Innocent,” Love says, smiling mysteriously. “Isn’t that obvious?” Okay, how about claims that you punched out four people last year, including K-records-Beats Happening’s Calvin Johnson, British writer Victoria Clarke, and a young female Nirvana fan who called her “Courtney Whore” in a Seattle 7-Eleven? “There’s a lot more to those stories, but I don’t intend to go into it.” Several journalists told me they’d received threatening phone messages after criticizing her in print. “So?” When I mention Cobain’s interest in guns, she cuts me off with a glower. Bringing up last year’s legal battle to keep custody of Frances Bean (a result of the Vanity Fair drug inferences) only magnifies the glower. On a lighter note, Lydia Lunch recently accused Love of ripping off her persona. “That’s too bad, because I admire her a lot.” Well, how about the fact that a lot of people just think you’re a mean, horrible person?

“Look,” Love says. “Years ago in a certain town, my reputation had gotten so bad that every time I went to a party, I was expected to burn the place down and knock out every window. So I would go into social situations and try my best to be really graceful and quiet and aloof. But sometimes when people are bearing down on you so hard, and want you to behave in a certain way, you just do it because you know you can.

“I’m so busy these days pleading with everyone that I’m lucid, that I’m educated, that I’m middle-class,” she continues. “It’s stupid. If you ask me, why aren’t people on the cases of the real assholes of this world, like Axl Rose and Steve Albini, both of whom should be exterminated. Really, they should leave on a shuttle to the sun. They shouldn’t be on the earth. Because they’re not good for anything.”

I’d been told by a mutual friend that Love tends to feel comfortable around gay men “as long as they don’t like disco.” Hoping to warm the atmosphere a little, I drop the names of a few famous actors I bedded when younger, and sure enough she giddily spills some beans herself. She practically begs me to “out” a notoriously homophobic music producer. Sorry. We move on. She has a few less-than-flattering adjectives for Evan Dando’s physique. “I’m the one that got him to stop taking off his shirt all the time,” she says. Then there’s the sad tale of her arch-enemy Axl Rose’s rapidly receding hairline, and his crazed search for a cure. “That’s what happens when you mix Prozac and heroin.” Finally, she regales me with a long, hilarious story about how Eddie Van Halen showed up backstage at a recent Nirvana show and practically begged to join them onstage fo the encore, completely oblivious to the fact that bands like Nirvana exist partly to destroy dinosaurs like himself.

Love’s proud of the band’s early work, especially its first LP, Pretty on the Inside, co-produced by Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon, a hero of Love’s, and Gumball’s Don Fleming. Still, she says, “That record was me posing in a lot of ways. It was the truth, but it was also me catching up with all my hip peers who’d gone all indie on me, and who made fun of me for liking R.E.M. And the Smiths. I’d done the whole punk thing, sleeping on floors in piss and beer, and waking up with the guy with the fucking mohawk and the skateboards and the speed and the whole goddamned thing. But I hated it. I’d outgrown it by the time I was 17.” She pauses, grabs a glass of fizzy water, and takes a huge gulp. “But fuck people if they didn’t guess it the first time around,” she continues, eyes blurring with anger. “If they didn’t get the lucidity. If it’s one thing I am, it’s lucid. I know that’s not a very heavy word like intellectual or whatever, but still, to take away my lucidity, that pisses me off.”

Live Through This is both a scruffier and more commercial record than Pretty on the Inside. The angsty rants of yore remain, but they’re decorated with a lot more poetry. Milk (as in mother’s) is a recurring motif, as is dismemberment. Female victimization remains the overall theme, this time depersonalized into odd, accusatory mini-narratives in which a variety of female characters receive the protection of Love’s tense, manic-depressive singing. Hers is a natural songwriting talent, full of excellent instincts, and yet wildly unsophisticated. All of which makes Love, in some ways, a more intriguing figure than, say, Polly Harvey, Tanya Donelly, or Liz Phair, each of whom, idiosyncrasies aside, is a traditional talent with an inordinate knack for the pop tune. It’s not inconceivable that Love might have ended up some kind of peroxided Joni Mitchell if it weren’t for the musical gifts of the diligent, like-minded Erlandson, and her unstoppable need to fuck with rock music’s male-heavy history.

“Like I was talking to Sophie…” It’s a few minutes later, and Love’s relaxing again. “Sophie’s done a bunch of Björk videos. And Björk is seen as the Icelandic elf child-woman. But Björk wants to be seen as more erotic. And I’m like, ‘Why?’ Elf child-woman is a good job. And my job as rock’s bad girl is good, too. I should just stop trying to correct people’s impressions.”

I understand, I say, but it’s strange that you’re written off as one-dimensional and didactic when your lyrics, if anything, tend to err on the side of the abstract.

“That’s because I’m not intelligent enough to write direct narratives,” she says sarcastically. “I’ve always worked really hard on my lyrics, even when my playing was for shit. So it’s weird that when I try to work in different styles, to juxtapose ideas in a careful way that isn’t pompous and Byronic, it’s just taken as vulgar. The whole cliché of women being cathartic really pisses me off. You know, ‘Oh, this is therapy for me. I’d die if I didn’t write this.’ Eddie Vedder says shit like that. Fuck you.”

Misogyny’s been a big shock to Love. After all, her parents were ’60s quasi-liberals bent on showing their daughter life’s brightest profile. The first record she owned was Free To Be You and Me. There was a copy of Our Bodies, Our Selves sitting on the family toilet for years. She grew up thinking books and records like these were the culture’s official textbooks. And she remains an avid reader of feminist theorists like Susan Faludi, Judith Butler, Camille Paglia, and Naomi Wolf, though her face crinkles up at the mention of the latter’s newest book. “Ugh. Wimp,” she crows.

I mention a riot grrrl show she’d helped organize in London last year. Rumor had it the show was a critical and financial disaster, despite the participation of name acts like Huggy Bear, Bratmobile, and Hole. Since that fiasco, the riot grrrl phenomenon has been treated a lot less reverently in the British music papers. “Yeah, it didn’t work,” she says, echoing the opinion of other Hole members, male and female. “But then the whole riot grrrl thing is so… well, for one thing, the Women’s Studies program at Evergreen State College, Olympia, where a lot of these bands come from, is notorious for being one of the worst programs in the country. It’s man-hating, and it doesn’t produce very intelligent people in that field. So you’ve got these girls starting bands, saying, ‘Well, they printed our picture in the Melody Maker, why aren’t we getting any royalties?”.

There is a lot written about Live Through This. 1994 is perhaps the greatest ever year for music, though I don’t think Hole’s second studio album gets as much praise and respect as the biggest from that year. I want to get some background and insight into this classic. I am going to end with Pitchfork and their 10/10 review of Live Through This. You can buy this masterpiece on vinyl. I will interrupt the features with one about the woman who appears on the cover of Live Through This, as it is one of the most recognisable and eye-catching shots of the 1990s. A cover that stands with the best of them. However, there is a fascinating story behind it and the aftermath for the cover star. I want to move to this feature from last year. They write how “Courtney Love bare her soul on an alt.rock classic that still surprises”:

“Incredibly melodic but with a punk streak, Live Through This proved that Hole and its antagonistic frontwoman, Courtney Love, could deliver more than just tabloid fodder. It remains a living document of a scene, a cultural moment, and a story of survival at all costs.

Hole’s first record, 1991’s Pretty On The Inside, had earned them considerable street cred. It’s a sludgy assault on the senses with a no-wave, atonal sound that reflected the influence of the album’s producer, Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon. In the three years since its release, however, the band’s profile had been raised significantly. Love and Cobain got married, had a child, and became the poster couple for grunge; the controversial Vanity Fair profile hit (in which Love was photographed baring her pregnant belly, and the magazine asked “if the pair were the grunge John and Yoko? Or the next Sid and Nancy?”); and there was a bidding war for Hole’s next record. The group ended up signing to Nirvana’s label, Geffen, and changed their line-up to start recording their major-label debut.

Love was unabashedly ambitious and not preoccupied with such trivial 90s concerns as “selling out.” With Live Through This, she set out to make a commercial record that also proved Hole was a legitimate band to be reckoned with. After Hole’s original drummer, Caroline Rue, left, Love and co-founder Eric Erlandson recruited Patty Schemel at Cobain’s suggestion, along with and their ace in the hole, bassist Kristen Pfaff, who brought a new energy and polish to the band.

Produced by Sean Slade and Paul Q Kolderie (who’d produced Radiohead’s Pablo Honey), Live Through This captured the band’s raw primal energy while still being an impeccably structured album with codas, choruses, and plenty of hooks, coalescing around Love’s emotional ferocity. The influences were clearly there (Pixies, Joy Division) but the band progressed beyond 80s post-punk retread to create 38 minutes of anthemic punk perfection.

From its blistering opening number, “Violet,” it was clear that Love wasn’t pulling any punches. While some easily recall their favorite chorus off an album, Live Through This is remembered for its screaming chants and ferocious drumming by Patty Schemel, inviting you to pour oil on the fire that is Courtney Love. You don’t sing along, you scream along.

Initially written in 1991, “Violet” became a live trademark during the group’s touring years before it became the album opener. Like Love herself, it’s full of contradictions, calling out the sexually exploitative nature of relationships while simultaneously inviting it upon herself: “Well they get what they want, and they never want it again/Go on, take everything, take everything, I want you to.” “Violet” sets the tone for the whole album, facilitating between intimate, quiet verses to the raging chorus, just as Love easily switches from victim to aggressor to create a dramatic tension that never breaks.

On “Miss World” – and, subsequently, every other track – Love addresses the listener directly, not necessarily as the perpetrator of all these problems but as complicit participants in society’s patriarchal ills. The song starts out softly melodic until the chorus erupts, repeating itself until it becomes a kind of invocation. Even the cover of Live Through This speaks to the album’s themes (desire, degradation, celebrity, and survival), featuring a disheveled Miss World beauty queen who could be a stand-in for Love herself, realizing that a crown does not always bring glory.

Every part of Love’s presentation was an extension of her music, from her intentionally make-up-smeared face to her ragged babydoll dresses. Both the lyrics and imagery for “Doll Parts,” and its accompanying video, show Love both acknowledging how society views women as objects while equally striving to be one. Both “Violet” and “Doll Parts” were early demos that showed Love’s maturation as a songwriter and helped to break the album, along with Erlandson’s tight arrangements.

The album gets its title from a lyric in “Asking For It,” which also references the often-used retort in cases of sexual assault. While never explicitly stated, the song is said to be inspired by an incident where Love was assaulted by a crowd after stage-diving during their 1991 tour with Mudhoney. It’s songs like these that make Love’s lyrics seem more autobiographical than perhaps initially intended. The same could be said for “I Think That I Would Die,” which references her child being taken away. Which makes it all the more interesting that some of the most pointed criticism of the album comes from Hole’s fiery cover of Young Marble Giants’ “Credit In The Straight World,” which calls out their critics and indie rock snobs. It begins with a kind of Gregorian chant before launching into a dual-bass and guitar assault courtesy of Erlandson and Pfaff.

While often compared to the adjacent riot grrrl movement, Love makes it clear that she’s not part of the Washington scene led by Bikini Kill, Sleater-Kinney, and Bratmobile, singing, “Well I went to school in Olympia/Everyone’s the same/And so are you, in Olympia,” on the closing track, “Rock Star.” Love’s female peers also become the central target on “She Walks On Me,” a song that further drives Hole apart from any kind of established scene. Despite its rebellious mocking tone, “Rock Star” also includes one of the more hopeful moments on Live Through This: just as the song seems to fade out, you hear Love insist: “No, we’re not done”.

I am coming to SPIN again for this feature published in 2024 around the thirtieth anniversary of the magnus opus that is Live Through This. In it, Hole’s drummer Patty Schemel reflects “how the album continues to resonate, holding a special place in the hearts of queer and trans fans”. There might be some who have never heard Hole or Live Through This. I don’t think it is a case of having to be around in 1994. Live Through This is such an influential album, and you can hear it affecting artists today:

“The album is more than queer-coded—it has queer lineages; its feeling, sounds, and themes were driven by queer punk drummer Patty Schemel’s beats and ability to amplify Courtney Love’s words and emotion like no other drummer could do.

“When you’re a kid and don’t feel like you belong and there’s someone saying they’re weird and have so much going on and they’re angry too, we spoke to everybody with that feeling,” Schemel told me, reflecting on how queer people have found a sense of empowerment in Hole’s music and lyrics. At readings of her memoir, Hit So Hard, fans often tell her the band’s music saved them.

When Schemel went into the studio, she had no idea that the album would become so successful. She wanted to prove herself as a drummer, and Hole wanted to prove themselves as a band, not just Kurt Cobain’s wife’s band.

In August 1995, Schemel came out as a lesbian in Rolling Stone magazine while the band were promoting Live Through This, a move ahead of its time. She felt inspired by the active queer punk scene, specifically Phranc, Roddy Bottum of Faith No More, Rob Halford of Judas Priest, and zinester and bassist of Team Dresch, Donna Dresch.

“Once I came out, I was like, ‘I’m never gonna hide it again. I’m never gonna feel bad about being who I am.’ Kurt would say it was okay to be gay, just like he said in the Incesticide liner notes, and people listened to that. I didn’t want to hide and not share my true self, because up until I was 18 I felt horrible about being gay. Punk rock saved me. I found other people who were freaky like me. Playing drums, it was okay for me to consider coming out.”

Schemel’s drums are integral to the power of Live Through This. The songs were collectively written at rehearsals, where the band would work through ideas at length, finding what clicked. Love always had big stacks of lyrics, and guitarist Eric Erlandson would always record their rehearsals since Love had trouble remembering her parts. “Her guitar playing got kind of good,” Schemel remembered, “but she didn’t want to focus on that.”

Since Love always wanted to be wherever Cobain was, Schemel would often travel with the couple. Album rehearsals started at Jabberjaw in L.A. but happened mostly at the Hole rehearsal space in Seattle, and in a few out-of-town writing sessions: one in San Francisco at the Melvins’ rehearsal space and another in Rio De Janeiro, when Love and Schemel used Nirvana’s Rock in Rio rehearsal room to write “She Walks Over Me” along with fellow queer punk musician, Nirvana roadie, and ex-Exploited guitarist Big John Duncan who, according to Schemel, played bass and suggested ideas.

“When I joined the band, the songs started to become a little more shaped, with more layers and form,” Schemel remembered, remarking on how she and Pfaff became a foundation together. “She made me feel so supported. All of her ideas were really cool! For those quiet middle sections where Courtney wanted to do these pretty little REM [style] picking things, like the twinkly things on ‘I Think That I Would Die.’ Courtney always had to have the last word. [Laughs.] But I felt that we kind of became a new band.”

Live Through This was the first and last album the group with this specific lineup got to record together, due to the untimely passing of Pfaff in June 1994—just two months after the album was released.

Hole recorded Live Through This at Triclops Sound in Marietta, Georgia, recommended to them by the Smashing Pumpkins, who had just wrapped up sessions for Siamese Dream. Hole was welcomed to the studio by a fax from Amy Ray, inviting the band to hang out. “Courtney was like, ‘Patty, I think this fax must be for you! It’s the Indigo Girls!’ And I was like, ‘Of course it is.’” According to Schemel, Love was constantly checking the fax machine for messages from Cobain. Unfortunately, due to a busy recording schedule, they never got to meet up with the Indigo Girls, but they did fly to New York to see Nirvana on Saturday Night Live”.

In 2019, the photographer who shot the cover of Hole’s Live Through This, Ellen von Unwerth, shared her memories and reflections with Another Mag. Courtney Love was inspired by an infamous scene in the 1976 film, Carrie. There is so much power in that image of the woman, model Leilani Bishop, and her expression. It still resonates to this day in terms of how engaging it is. It is a cover you keep coming back to, transfixed by that image:

“Courtney Love recently posted a screenshot to her Instagram account from Rolling Stone’s website which – on that same day – released its 50 Greatest Grunge Albums. Hole’s Live Through This came in at number four and almost 68,000 fans and followers liked that image, showering her with a barrage of hearts and congratulations in the comments. Lead vocalist Love, as well as guitarist Eric Erlandson, bassist Kristen Pfaff and drummer Patty Schemel crafted a 90s era-defining masterpiece that has been canonised on virtually every top music list of that decade. The raw, unapologetic honesty of the lyrics, brought to life by Love’s sweet yet deeply sinister vocals, makes the album unforgettable. The same could be said about the spine-tingling album cover image, shot by fashion world favourite, Ellen von Unwerth.

Model Leilani Bishop – the only person on the album cover – embodied an intentionally manic, prom-queen-gone-wrong look. The smudged eye make-up, vintage-inspired feathery locks topped with a dainty tiara, and her awkward embrace of a floral bouquet meant to evoke a certain classic horror film. Speaking to AnOther, Von Unwerth recalls the days before the photo shoot in Los Angeles. “Courtney Love called me,” she says. “We were on the phone for one hour. I didn’t say much but listened, and Courtney had the idea of re-enacting the scene of the [1976] movie Carrie, which I loved, too.” Von Unwerth also reveals that she and Love managed to click from the beginning, adding, “I just met her the night before the shoot wearing her famous schoolgirl dress. We had some drinks and connected instantly.”

Unfortunately, Von Unwerth had not listened to Live Through This prior to the photo shoot. But in her eyes, that didn’t matter. “The album was still in the making, but I was a big fan of Kurt Cobain and was sure that his girls would produce something equally cool. Besides, I go with the flow. I heard the music afterwards and loved it.”

Hole’s second studio album, Live Through This was an anomaly at the time. Love and Erlandson wrote the songs and broached topics like feminism, violence against women, beauty, postpartum depression, motherhood, feelings of self-doubt and relationship woes. Love once openly admitted that she was competing with her husband, Kurt Cobain, during the making of the album. Though many critics alleged that Cobain had a hand in writing the album (he didn’t), his undeniable presence looms like a dark cloud over the album. He sang uncredited back-up vocals with Pfaff on Asking for It and Softer, Softest.

With tragic timing, DGC Records slated the release date for Live Through This on April 12, 1994, seven days after Cobain committed suicide. Three months later, Love and the band suffered another blow when bassist Pfaff died of an overdose.

Von Unwerth unknowingly captured the turbulence surrounding Live Through This in one frame. Bishop’s effusive, open-mouth expression on the cover album speaks volumes as loud as Love’s voice. Von Unwerth says, “I just had done several shoots with [Bishop] and really loved her cool rock and roll attitude.” But how did she evoke such reaction from Bishop? Von Unwerth admits, “This is what I do. It’s like being a movie director.” She also remembered being self-assured when she saw the selects after they had wrapped the shoot. “We all felt that we nailed it,” she says.

And that she did. While Von Unwerth’s diverse portfolio features art from other bands’ album covers like Bananarama, Belinda Carlisle, Janet Jackson, Dido, Britney Spears and Rihanna, somehow Live Through This stands out as a chillingly authentic, visual interpretation of Hole’s music. Von Unwerth naturally connected the band to its fans through a harmonious mix of rock and roll attitude and highly stylised photographical prowess. 25 years on, Von Unwerth declares, “I am very proud that I was part of this album, this band, and this time in music and cherish every moment of it.” And if those “best of” lists are any testament to Von Unwerth’s work, Billboard – back in 2015 – placed Live Through This at number 12 in their 50 Greatest Cover Albums of All Time”.

In 2018, Pitchfork revisited Hole’s Live Through This. Awarding it a perfect score, it is an album of depth, righteous anger and some of the most important music of the '90s. Nearly thirty-two years after its release and Hole’s second studio album still sounds like nothing else. This distinct work, you can hear its influence adopted and adapted by so many artists:

“Try to imagine a famous woman who screams for a living today. Not alternative, punk-magazine famous, but American monoculture famous, platinum-selling-album famous, so famous her drug mishaps make headlines in Mexican newspapers, so famous rumors and conspiracies about her celebrity marriage hound her for decades. This woman doesn’t let out sing-screams or tinny emo yelps, but raw, diaphragmatic bellows—or, as David Fricke put it in his Rolling Stone review of Hole’s 1994 album, Live Through This, a “corrosive, lunatic wail.”

He was wrong on the second point: There’s no lunacy on Hole’s records. But there is anger, female anger, which, to a man’s ear, historically scans as madness. Lead singer Courtney Love often told reporters that she named her band after a line in Euripides’ Medea. “There’s a hole that pierces right through me,” it supposedly goes, though you won’t find it in any common translation of the ancient play. It’s apocryphal, or misremembered, or Love made it up to complicate the name’s obvious double entendre—either way, it makes a great myth. A band foregrounding female rage takes its name from the angriest woman in the Western canon, a woman so angry at her husband’s betrayal she kills their children just so he will feel her pain in his bones.

Like all female revenge fantasies written by men, Medea carries a grain of neurosis about how women might retaliate for their subjugation. It is easier, still, for men to express these anxieties by way of violent fantasy than it is for women to communicate their anger at all. In a 1996 New York magazine cover story on women alternative singers entitled “Feminism Rocks,” Kim France, the founding editor of Lucky who also worked as New York’s deputy editor, paraphrased feminist journalist and author Susan Faludi: “While our culture admires the angry young man, who is perceived as heroic and sexy, it can’t find anything but scorn for the angry young woman, who is seen as emasculating and bitter.” This was true for Love, who watched grunge break through to the mainstream only to find that the freedom and rebellion it promised was reserved for her male counterparts. In grunge, men could be scruffy and rude and defy gender norms—they could be rawer than the men modeled in synth-pop music videos or hair metal concerts a few years prior. Women, for all the space afforded them in the subculture’s spotlight moment, might as well have been Lilith.

Hole’s second album, Live Through This, famously came out four days after Love’s husband, Kurt Cobain, was found dead at their home in Seattle. The sudden tragedy threatened to swallow the music, to say nothing of the genre and social movement in which it was encased. Here was a dead rock god, and here was the woman who survived him. Even the album’s title alluded to Love’s endurance through a ground-shaking trauma, though of course she had written the title about surviving her fame, surviving her fraught association with the most beloved man in rock, surviving her pregnancy with their child, surviving the tabloid rumors that would—and still do—swarm her as a result.

“I sometimes feel that no one’s taken the time to write about certain things in rock, that there’s a certain female point of view that’s never been given space,” Love told Sidelines in 1991, the same year Hole released their first album, Pretty on the Inside. While there were plenty of rock songs written by men about hounding and abusing women, there were few about being hounded and abused. The rock canon, like all the others, fiercely guarded its male subjectivity, and Love wanted to break through its ranks.

Love wrote about sexual violence with a snarl, too, but a heavier, more knowing one. “Was she asking for it?/Was she asking nice?” she poses on the seething “Asking for It.” “If she was asking for it/Did she ask you twice?” The song, she’s said, was inspired by a stage dive that took a wrong turn. She leapt into the audience to crowd-surf during a show, and found the crowd ready to devour her. “Suddenly, it was like my dress was being torn off me, my underwear was being torn off me, people were putting their fingers inside of me and grabbing my breasts really hard, screaming things in my ears like ‘pussy-whore-cunt,’” she said. Whatever covenant binds fan and artist, whatever gives the latter power over the former, didn’t apply to Hole—not in totality, at least; not to the extent that it would keep a singer who was also a woman from being molested by her audience in public.

Live Through This refers to autobiographical traumas, but it is not a confessional record. “The whole cliché of women being cathartic really pisses me off,” Love said in a 1994 Spin cover story. “You know, ‘Oh, this is therapy for me. I’d die if I didn’t write this.’ Eddie Vedder says shit like that. Fuck you.” Her lyrics don’t hit like spleen-venting. They’re analytical, no matter how viscerally she howls them, and their insight transcends their origins. Throughout the record, Love speaks to the atomization of the female form that takes place in the eye of the misogynist. To the ogler, a woman is never whole. She’s shards: lips, hair, tits, ass, whatever can be grabbed without consequence, whatever can be bought and sold. Love would know, having stripped for a living before the band broke big, having made a career of, among other things, being looked at. She sings of “pieces of Jennifer’s body.” On “Doll Parts,” against halting guitar chords, she sings about how she’s “doll eyes, doll mouth, doll legs.” Her multiplicity is underscored by backing harmonies from Hole bassist Kristen Pfaff and guest vocalist Dana Kletter, who chime in with the indelible line: “I want to be the girl with the most cake.”

As much as it concerns trauma and misogyny, Live Through This, like all great rock records, quakes with desire. Love deciphers what it means to be an object of desire, but she also plays a woman who wants ravenously. Her wanting, at the time, was a terror; she inspired so much vitriol in part because she refused to be passive, refused to accommodate a man’s hunger without indulging her own. She would not be a vessel or a muse. Her husband did not cast her in the drama of his life. She wanted him and chased him down, and then she wanted their child, and she believed that her desire mattered, that it had substance. “I went through all the shit and pain and inconvenience of being pregnant for nine whole fucking months because I wanted some of his beautiful genes in there, in that child,” Love told Melody Maker, in a profile that called her “a one-woman spite factory” in its tagline, in February of 1994. “I wanted his babies. I saw something I wanted, and I got it. What’s wrong with that?”.

I wanted to dig deep for this Beneath the Sleeve. Hole’s Live Through This is one of the greatest albums ever, and it is one I remember from the 1990s. A fan of Nirvana, I discovered Hole through them. Considering the trauma Courtney Love faced in the wake of Kurt Cobain’s death, she showed so much strength, dignity and bravery. I would suggest people watch the new Courtney Love documentary, Antiheroine. Also, to be able to promote an album like Live Through This and deal with questions around Cobain. In an America that has a misogynistic, transphobic, hateful President who puts women’s rights bottom of his agenda and has split a country, you feel Live Through This is more important needed than ever! This 1994-released album is…

A staggering work.