FEATURE:

Kate Bush: Them Heavy People: The Extraordinary Characters in Her Songs

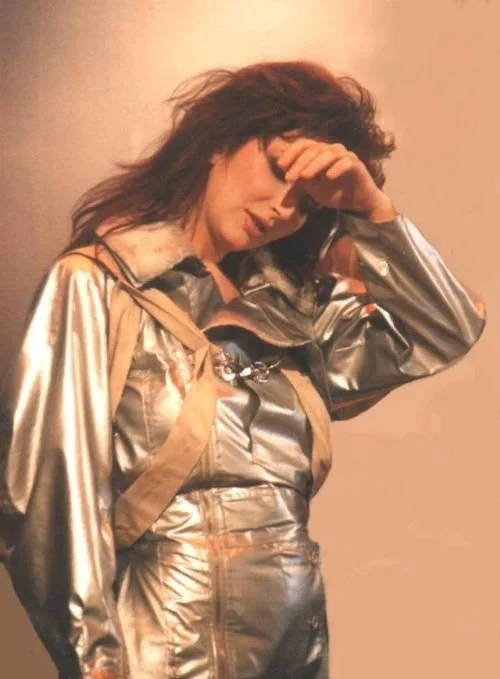

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush in 1980 for a live performance of Delius (Song of Summer) from her third studio album, Never for Ever

Frederick Delius (Delius (Song of Summer)/Noah (The Big Sky)

__________

FOR this part of the…

PHOTO CREDIT: John Carder Bush

series where I look at characters included in Kate Bush songs, I am pairing two albums released five years apart. I will get to Hounds of Love and the second biblical character from the album I have included in this run. However, I am starting out with a real-life character from Never for Ever and a song which ranks alongside one of the best from Bush’s early career. There is a lot to discuss when it comes to Frederick Delius and Delius (Song of Summer). Let’s start off with some background to this song. I am turning to the Kate Bush Encyclopedia: “Delius (Song Of Summer)’ is a song written by Kate Bush as a tribute to the English composer Frederick Delius. The song was inspired by Ken Russell’s film Song of Summer, made for the BBC’s programme Omnibus, which Kate had watched when she was ten years old. In his twenties, Delius contracted syphilis. When he became wheelchair bound as he became older, a young English admirer Eric Fenby volunteered his services as unpaid amanuensis. Between 1928 and 1933 he took down his compositions from dictation, and helping him revise earlier works. The song was released on the album Never For Ever and as the B-side of the single Army Dreamers”. Although there is not a lot written from Kate Bush in terms of why she included Frederick Delius in a song and why she was inspired to do this, Never for Ever was a very interesting album. Released in September 1980, it went to number one in the U.K. It was the first time Kate Bush was coproducing her music. Working with Jon Kelly, although technology did play more of a role in The Dreaming (1982) and Hounds of Love (1985), you can hear some of its influence on Never for Ever. Specifically the Fairlight CMI. In terms of the options open for Bush as a songwriter, this was a really important time. A much broader palette she could work from. You can hear that on a song like Delius (Song of Summer). Whereas before Bush had to manipulate her own voice and was tied to the piano and limited as to what she could achieve on her first two albums, with the Fairlight CMI, she could programme sound effects and feed her vice through this equipment to create new worlds.

Bush was instantly attracted to the Fairlight CMI. She said how she could create this human, emotional and animal sound that did not feel like it was machine-made. If co-producer Jon Kelly was a bit more old-skool and was confused why an instrument could not be played and why it had to be fed through the Fairlight CMI, it was clear that Kate Bush knew that modern technology could take her music to new heights. She could be much more imaginative as a songwriter. It is interesting about the timing of the Fairlight CMI. It is all over The Dreaming but was a little late to impact Never for Ever. I guess she would have liked to have used it more but she was wrestling with the technology. Working out of Abbey Road Studio and there were multiple multi-track machines loaded up. Getting into this tangle, it was not always a smooth process. However, you can feel something taking shape and Bush’s music transforming. Never for Ever a big step on from 1978’s Lionheart. By all accounts, the recording and atmosphere at Abbey Road was fun and creative. Sessions did go long into the night and Bush was typically a night creature. She was experimenting and throwing quite a lot into the mix. Delius (Song of Summer) is sparser than other songs on Never for Ever, though you can feel sounds and vocal elements that were centred around the Fairlight CMI. I think in the case of Delius (Song of Summer) the Roland synthesiser provided the percussion sound. Whereas the technology might not be the most notable element of this song, I feel that you can feel Bush’s writing definitely opening up and expanding. Bass voices by Paddy Bush and Ian Bairnson. Paddy Bush playing the sitar. Such a rich composition and a quirky song, there is also this level of preciousness’ that is worth noting. How Bush was ten when she watched Omnibus and was struck enough where she would later write a song about this underrated English composer.

It is not the only example of Bush seeing something on T.V. and that leading to a song. A 1967 adaptation of Wuthering Heights inspired her 1978 debut single. In the case of Delius (Song of Summer), she kept the memory of Omnibus in her mind for a decade before letting it out through song. It makes me wonder about a certain affluence. Song of Summer is a 1968 black-and-white television episode co-written, produced, and directed by Ken Russell for the BBC's Omnibus series which was first broadcast on 15th September, 1968. I wonder how many people in the U.K. had a television and how common it was. It seems like Bush and her family watched quite a bit of T.V. and there was all this culture around. In 1968, she was living at East Wickham Farm in Welling. It was this middle-class part of Kent, so it might have been more common than other parts of the U.K. I do wonder how many of Kate Bush’s songs would have never been written were it not for television. How many ten-year-olds would have watched something as high-brow as an Omnibus show and both been engrossed and then thought of a song afterwards?! The closing line of Delius (Song of Summer), “In B. Fenby”, was written by someone who did not know she would soon meet Eric Fenby. Fenby, as this big fan of Frederick Delius, was devoted to the point where he transcribed and noted down compositions when Delius became wheelchair-bound. Bush met an older Eric Fenby when she appeared on The Russell Harty Show and performed a version of it alongside Paddy Bush (who played the part of Delius in a wheelchair).

A couple of other things to note about Delius (Song of Summer). That link to Classical music. When it comes to Kate Bush, we often hear about her influences in connection with popular music. Artists like David Bowie and Roxy Music. However, growing up in a household where there would have been Classical music played and you feel her father in particular was a fan of that genre, it is surprise that she did not explore this more. Her father was a fan of Chopin, but Bush seems to have been more inspired by other genres like Pop and Folk. However, strings and orchestration did come more into her work later. Something epic and symphonic appears on Never for Ever in the form of Breathing. The beautiful strings on The Dreaming’s Houdini. Hounds of Love’s Hello Earth operation and classical. One of these what-if questions relates to Kate Bush composing for film and T.V. I often wonder what it would be like if she did compose. You can hear her compositional flair and that sense of scale on albums like Hounds of Love, Aerial (2005) and even 50 Words for Snow (2011). I do wonder if a future album might take this even further. Though the work of Frederick Delius is not something you can directly hear in Bush’s work, it is noteworthy that she wanted to write a song about a Classical composer and, soon after, her work would become more symphonic and almost Classic in some ways. The unique subject matter is something typically Kate Bush. We talk about songs like Wuthering Heights and how inspired that is. People do not discuss Delius (Song of Summer) and its brilliance. There are not a lot of words in the song but each one is brilliantly evocative and incredible. “Ooh, ah, ooh, ah/Delius/Delius amat/Syphilus/Deus/Genius, ooh/To be sung of a summer night on the water/Ooh, on the water/“Ta, ta-ta!/Hmm/Ta, ta-ta!/In B, Fenby!”/To be sung of a summer night on the water/Ooh, on the water/On the water”. Humorous, strange and conversational, it is kudos to Bush as a producer and songwriter. Bush using Latin in the song.

I want to end this half with a fascinating article from Dreams of Orgonon that I have sourced before. The last conversation idea around Delius (Song of Summer) is Bush’s use of real-life people in her songs. Whilst most of her characters are fictional and invented by her, this is a rare case of Bush inspired by a well-known figure. However, I wonder how many people knew about Frederick Delius in 1980? A composer who died in 1934, few knew about Delius’s music and story when they heard this song on Never for Ever:

“To explain what Bush doesn’t, Frederick Theodore Albert Delius began his career as a full-time composer in Paris in 1886, channeling the influence of black music (which he discovered while failing to manage a Florida orange plantation) and European composers such as Wagner and Grieg into his own orchestral pieces (in a declaration of emotional hedonism, he described music as “an outburst of the soul” which is “addressed and should appeal instantly to the soul of the listener”). By the 1890s, he became popular in Imperial Germany thanks to the promotional efforts of German conductors. It took longer for Delius’ music to take off in his native Britain, but it eventually gained enough popular heft for Westminster to hold a six-day Delius festival in the late 1920s. By that point, Delius had contracted tertiary syphilis from extramarital affairs he’d conducted in Paris and was blind and paralyzed. In the final stage of his life, he was tended by his astonishingly dedicated wife Jelka Rosen, who gave up a genuinely successful art career to be his caretaker. Yet even with his devastating syphilis, he remained creative. From 1928 to 1934, Delius was assisted in his compositional efforts by a fellow Yorkshireman, Eric Fenby. For the duration of that time, Fenby served as Delius’ amanuensis, assisting him in the composition of some of his better-known pieces, such as the tone poem A Song of Summer, one of his more useful works for our purposes, as it provides the title of Ken Russell’s Delius biopic.

In terms of progenitors, Delius and Bush are operate in adjacent but separate traditions. Delius was heavily influenced by American music, particularly black music. He was fonder of popular music than some of his contemporaries (there’s a true-to-life scene in the film A Song of Summer where Delius jauntily enjoys listening to “Old Man River”) and was heavily influenced by his nostalgia for his plantation days. According to Delius, the black workers on the plantation “showed a truly wonderful sense of musicianship and harmonic resource in the instinctive way in which they treated a melody, and, hearing their singing in such romantic surroundings, it was then and there that I first felt the urge to express myself in music.” The implications of this statement are mixed in nature. On the one hand, channeling the innovations of black music into critically respected symphonies in the Jim Crow era was a step forward in terms of taking the musical abilities of black people seriously. Alternatively, there’s a distressing mystification of exploited black workers in Delius’ description. Their labor is something for him to enjoy personally, rather than a way for these doubtlessly persecuted people to alleviate the astounding difficulties of plantation work. As is the norm for popular music, Delius treats black people as inspirations for his own creations rather than innovators who paved the way for 20th century music.

Bush’s relationship to black music has more distance. I’ve expounded on how Bush is primarily a British songwriter influenced by English artists. Those English artists, such as Bowie and Ferry, were in turn publicly and unashamedly influenced by American black music. Bush’s own terribly white style has less to do with R&B. Lionheart is a quasi-jazz album, and Bush was a fan of Billie Holiday, but Holiday’s influence on her work isn’t nearly as obvious as the watermark of Ziggy Stardust or The Wall. It’s not that Bush doesn’t engage with the musical creations of racial minorities — she will later in her career, with results that range from well-intentioned misfires like “The Dreaming” and blatantly offensive works like “Eat the Music.” When we get to The Dreaming, we’ll have to talk about the rise of world music and Bush’s part in it, as The Dreaming pays more attention to ethnic minorities than the rest of her work (I’m going to spend a lot of the next few months arguing that The Dreaming is a flawed work of post-colonial horror). So while Delius is directly influenced by black music, Bush is only tangentially marked by it, in the same way that most artists who create popular music is going to touch on R&B or rock ‘n’ roll in some fashion. As things stand, both Delius and Bush have admiring but flawed views on black music, acknowledging its importance without fully understanding the struggles behind it.

“Delius (Song of Summer)” contains flashes of its subject’s life. “Oh, he’s a moody old man,” muses Bush, referring to Delius’ volatile behavior as reported by Fenby, then referencing Delius’ work by adding “song of summer in his hand.” The song plays out like a duet between Fenby and Delius — Fenby’s reserved nature and devout Catholicism often led to the young man becoming overwhelmed by his employer’s secularism and cantankerousness (Paddy Bush is heard gruffly saying “ta-ta-ta” and “in B, Fenby!”, quotes from Ken Russell’s film Song of Summer). The chorus, a sequence of Latin or Latin-ish phrases, sounds like a despairing yet awed prayer of elegy by Fenby: “Delius/Delius amat” (Bush continues to fail at foreign languages by attaching the third-person present “amat” to “Delius,” while also touching on Delius’ atheism), and the genuinely gut-busting rhyme of “syphilis/deus/genius,” the latter of which she pronounces in Latin. “Delius” is neither hagiographical nor harshly critical of its song — it simply evokes his ethos and how the people in his orbit perceived him.

Or at the very least, it perceives Delius according to filmmaker Ken Russell’s treatment of him. “Delius” is heavily indebted to Russell’s 1968 BBC adaptation of Eric Fenby’s memoir Delius as I Knew Him, called Song of Summer. The film is told through the perspective of Fenby (a young Christopher Gable, who Doctor Who fans might recognize), who initially approaches Delius as an admirer and quickly becomes a distant and subordinate collaborator to him. The Delius of the movie (Max Adrian, and yes Song of Summer doubles as a trivia game for Doctor Who fans) is not a legend nor a booming celebrity, but a foul-tempered geriatric has-been, confined by his illness and domineering personality. This could easily turn into a cynical story about how young creatives should never meet their heroes, but Song of Summer is smarter than that. While it doesn’t understate the fact that Delius was plainly an asshole, neither does it understate the human costs of his cruelty. There are some gorgeous scenes where Delius becomes fully animated by the power of music and creation, and Fenby, while alienated from his hero, is equally drawn in. Russell depicts two men whose struggles are both reconciled and exacerbated by the creative process. Russell’s script is imbued with psychological realness, which is granted to every character — Jelka Delius finally gets justice in an astonishing scene where she breaks down over her husband’s infidelity and cruelty. Typically for Ken Russell’s work, Song of Summer moves gracefully, with equal measures of ambivalence and clarity. Of the films Kate Bush has touched to date, this may be the best.

Recorded at Abbey Road Studio 2 during the sessions of January-June 1980. Released on Never for Ever on 7 September 1980. Music video shown during Dr. Hook and The Russell Harty Show on 7 April 1980 and 25 November 1980, respectively. Never performed live. Personnel: Kate Bush — vocals, piano, production. Roland — percussion (tongue-in-cheek credit on the album’s liner notes). Paddy Bush — Delius, sitar, bass voice. Alan Murphy — electric guitar. Ian Bairnson — bass voice. Preston Heyman — additional percussion. Jon Kelly — production, engineer. Pictures: Max Adrian & Christopher Gable in A Song of Summer (1968, dir. Ken Russell); Kate Bush in a swan dress”.

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush on the set of The Big Sky

I am going to move to a song from Hounds of Love that turns forty on 21st April. The fourth and final single from the masterpiece album, The Big Sky is my favourite track from Hounds of Love. If we hear God mentioned and prominent in Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God), then Noah is a more fleeting reference. However, I think that it is quite relevant. I will revisit a couple of interviews with Kate Bush that I have included in Kate Bush features, as it shows that The Big Sky was a hard song to put together. The Kate Bush Encyclopedia provide these valuable archive resources:

“The Big Sky’ was a song that changed a lot between the first version of it on the demo and the end product on the master tapes. As I mentioned in the earlier magazine, the demos are the masters, in that we now work straight in the 24-track studio when I’m writing the songs; but the structure of this song changed quite a lot. I wanted to steam along, and with the help of musicians such as Alan Murphy on guitar and Youth on bass, we accomplished quite a rock-and-roll feel for the track. Although this song did undergo two different drafts and the aforementioned players changed their arrangements dramatically, this is unusual in the case of most of the songs. (Kate Bush Club newsletter, Issue 18, 1985)

‘The Big Sky’ gave me terrible trouble, really, just as a song. I mean, you definitely do have relationships with some songs, and we had a lot of trouble getting on together and it was just one of those songs that kept changing – at one point every week – and, um…It was just a matter of trying to pin it down. Because it’s not often that I’ve written a song like that: when you come up with something that can literally take you to so many different tangents, so many different forms of the same song, that you just end up not knowing where you are with it. And, um…I just had to pin it down eventually, and that was a very strange beast. (Tony Myatt Interview, November 1985)”.

The takeaway is that The Big Sky came together slowly and through different stages. Given that the track is quite child-like in nature, almost like a homework assignment! The Big Sky is the owner of clouds and gazing up. A cloud that looks like Ireland. Clouds full of rain and weather connections. Hounds of Love is full of weather and water. The Ninth Wave on the second side and Cloudbusting on the first side. What is intriguing is that one of the loosest and most joyous songs was perhaps the most challenging to get together. I guess it happens with songs, but you listen to the album version and cannot hear any of that struggle. The bass part of this song is especially fascinating.

Hounds of Love as an album is often commending because it did not feature a lot of bass. However, I think that the bassline from Youth (Martin Glover) is remarkable. So frantic, energetic and groovy, it showcases the musical diversity of Hounds of Love. The Fairlight CMI plays a big role and there are synthesisers and electronic elements. However, some of its most powerful moments arrive when more traditional and human-led performances take centre stage. Some great handclapping from Charlie Morgan and Del Palmer. Morris Pert and Charlie Morgan on percussion and drums. Alan Murphy’s guitar. Paddy Bush on didgeridoo. Even though The Big Sky only reached thirty-seven, it did get a lot of critical love. In terms of how Bush was perceived by the press at this time, Hounds of Love reset things. Just before Hounds of Love came out in 1985, many in the press wrote her off and asked where she was. 1982’s The Dreaming got some positive reviews, though many found the album too strange and off-putting. Huge singles like Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God) and Hounds of Love won a lot of praise. Still picking up momentum in 1986, The Big Sky was met with acclaim. Even if Bush found it hard to get The Big Sky finished and it was this challenge, she did release it as a single. The music video is fantastic. Kate Bush directed it. After directing the Hounds of Love single video, this was her second solo effort as a director: “It was filmed on 19 March 1986 at Elstree Film Studios in the presence of a studio audience of about hundred fans. The Homeground fanzine was asked to get this audience together, and they did within two weeks. Two coaches took everyone from Manchester Square to Elstree studios early in the morning, after which the Homeground staff, who were cast as some of the aviators, were filmed, and finally the whole audience was admitted for the ‘crowd scenes’. The scenes were repeated until Kate had them as she wanted”.

When thinking about Noah in the lines, “This cloud, this cloud/Says “Noah/C’mon and build me an Ark.”/And if you’re coming, jump/‘Cause”. I have already featured biblical characters in this series. It is interesting that they feature sporadically on her albums. If God was used as this deal-broker in the most popular song from Hounds of Love, there is something more throwaway or less significant here. However, it is interesting that Bush mentioned Noah. The story of Noah in The Bible (Genesis 6–9) tells of a righteous man commanded by God to build a massive ark to save his family and pairs of every animal from a global flood, designed to purge the earth of rampant wickedness. The lyrics on The Big Sky is fascinating. I think it is this perfectly blend of this joyful, oblique and mysterious. The opening lines have always perplexed me in terms of exactly what they mean: “They look down/At the ground/Missing/But I never go in now”. I wonder exactly what those words mean. Who Bush is referring to when she sings “You never really understood me/You never really tried”. I know Bush wrote a lot of Hounds of Love in Ireland, and I am not sure whether The Big Sky was one of the songs written there. Because of the countryside and landscape of Dublin and maybe her mind thinking about clouds and the weather. The inclusion of Noah is inspired. It gives this sense of the epic and biblical to a song that could otherwise have been fluffy and infantile. It is a standout from Hounds of Love. If Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God), Cloudbusting and Hounds of Love are quite serious or deeper songs, I love that there is this free spirit and abandon on The Big Sky. Although it is a cloud talking to Noah rather than a physical embodiment of the biblical figure, it is another case of Bush using religious imagery to great effect.

It is interesting that Noah is perhaps more significant than we would imagine listening to the song through. For her fan club newsletter in 1985, Kate Bush spoke about The Big Sky and said this: “I used to do this a lot as a child, just watching the clouds go into different shapes. I think we forget these pleasures as adults. We don’t get as much time to enjoy those kinds of things, or think about them; we feel silly about what we used to do naturally. The song is also suggesting the coming of the next flood – how perhaps the “fools on the hills” will be the wise ones”. Bush connecting with her childhood and bringing that into the song. Also, something far grander and more serious. If Cloudbusting is a song about a machine that could make it rain, perhaps this is the result of that. A two-part epic. These seemingly harmless clouds in the sky that twist into the shape will summon something destructive. Is this literal rain or something political? Hounds of Love perhaps has fewer characters than some Kate Bush albums, though I feel they are among the most discussion-worthy. I will come to Cloudbusting and a piece of literature that inspired the song. There is also the Mother in Mother Stands for Comfort. Characters to be found through The Ninth Wave. Maybe the eponymous Hounds of Love too. However, Noah is inserted into a song that is partly whimsical and child-like. Maybe ominous in the sense that there is this coming flood, it is interesting how water is at the centre of Hounds of Love. The flood of The Big Sky and the sea and the heroine being stranded through The Ninth Wave. This article is titled Water, Music, and Transformation in The Ninth Wave by Kate Bush and makes some interesting observations: “Bush’s album skilfully frames water symbolically, historically and pop-culturally: the art of musical storytelling is accompanied by the symbolic dissection of the trope of water. With a peculiar blend of empathy, darkness, and gratitude, The Ninth Wave serves as an intriguing example of how mutability should not be perceived as a dangerous force but as a positive, or even a necessary one. Water is dangerous; there is no doubt about that, but without its transformative qualities, there would be no maturation of the individual. Since antiquity, the abyss of water has been a symbol of wisdom – mysterious, unfathomable, yet regenerative in its nature. Paradoxically, the threat that water poses functions as a catalyst for maturation. As the beginning of The Ninth Wave depicts, the destructive potential of water reveals what is indeed important for the individual trapped in dire straits, which is the connection to other human beings”. A fascinating English composer immortalised in Never for Ever’s Delius (Song of Summer) and a biblical figure treated in Hounds of Love’s The Big Sky, I wanted to pair them to show the sheer range of characters Bush uses in her songs. Kate Bush is a writer and storytelling…

LIKE no other.