FEATURE:

An Impossible Task…

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush in 2014/PHOTO CREDIT: Trevor Leighton

Ranking Kate Bush’s Album Covers

__________

I only titled…

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush in 1980/PHOTO CREDIT: Andy Phillips

this feature like that because it is impossible ranking Kate Bush’s album covers. They are all striking in their own way. However, since I last did a feature around her album covers, my opinion has changed. Perhaps not in terms of those I like least. However, I am extending this beyond her studio albums to include Before the Dawn (the 2016 live album for her 2014 residency) and The Whole Story (her 1986 greatest hits compilation). I am leaving out other albums such as Best of the Other Sides (2025). Many people talk about Kate Bush’s music, though the visual aspect is really important and plays its part. The album covers are almost as memorable and genius as the music. One might think her best covers are pretty obvious. However, for this feature, I am going to bring in my order. I am including the release date of each album, the standout tracks and the key cut. I will also drop in a review for the albums. Kate Bush’s albums covers are always so fascinating, so it has been tough deciding this ordering, though I was keen to make that decision. From Never for Ever’s cover which is a sketch and design from Nick Price, through to covers shot by her brother, John Carder Bush (including 1982’s The Dreaming and 1985’s Hounds of Love), there is so much to behold. Here are my views when it comes to deciding…

WHICH Kate Bush album covers are best.

____________

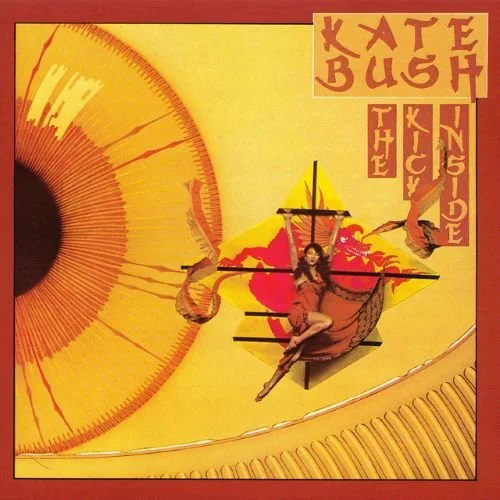

TEN: The Kick Inside (1978)

Release Date: 17th February, 1978

Review:

“The tale's been oft-told, but bears repeating: Discovered by a mutual friend of the Bush family as well as Pink Floyd's David Gilmour, Bush was signed on Gilmour's advice to EMI at 16. Given a large advance and three years, The Kick Inside was her extraordinary debut. To this day (unless you count the less palatable warblings of Tori Amos) nothing sounds like it.

Using mainly session musicians, The Kick Inside was the result of a record company actually allowing a young talent to blossom. Some of these songs were written when she was 13! Helmed by Gilmour's friend, Andrew Powell, it's a lush blend of piano grandiosity, vaguely uncomfortable reggae and intricate, intelligent, wonderful songs. All delivered in a voice that had no precedents. Even so, EMI wanted the dullest, most conventional track, James And The Cold Gun as the lead single, but Kate was no push over. At 19 she knew that the startling whoops and Bronte-influenced narrative of Wuthering Heights would be her make or break moment. Luckily she was allowed her head.

Of course not only did Wuthering Heights give her the first self-written number one by a female artist in the UK, (a stereotype-busting fact of huge proportions, sadly undermined by EMI's subsequent decision to market Bush as lycra-clad cheesecake), but it represented a level of articulacy, or at least literacy, that was unknown to the charts up until then. In fact, the whole album reads like a the product of a young, liberally-educated mind, trying to cram as much esoterica in as possible. Them Heavy People, the album's second hit may be a bouncy, reggae-lite confection, but it still manages to mention new age philosopher and teacher G I Gurdjieff. In interviews she was already dropping names like Kafka and Joyce, while she peppered her act with dance moves taught by Linsdsay Kemp. Showaddywaddy, this was not.

And this isn't to mention the sexual content. Ignoring the album's title itself, we have the full on expression of erotic joy in Feel It and L'Amour Looks Something Like You. Only in France had 19-year olds got away with this kind of stuff. A true child of the 60s vanguard in feminism, Strange Phenomena even concerns menstruation: Another first. Of course such density was decidedly English and middle class. Only the mushy, orchestral Man With The Child In His Eyes, was to make a mark in the US, but like all true artists, you always felt that Bush didn't really care about the commercial rewards. She was soon to abandon touring completely and steer her own fabulous course into rock history” – BBC

Standout Tracks: Moving, The Man with the Child in His Eyes, Them Heavy People

Key Cut: Wuthering Heights.

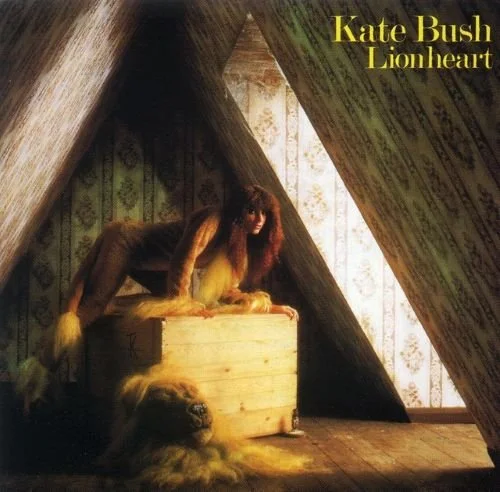

THREE: Lionheart (1978)

Release Date: 10th November, 1978

Review:

“Ok, here’s the party line on Kate Bush’s second album Lionheart. It was the “difficult second album”; rush released too soon after her stupendous debut, The Kick Inside. The material was under cooked, it was recorded hastily. It was a commercial disappointment. Lionheart has always been viewed as the gawky, homely sister to The Kick Inside. It languishes in the same purgatory as Fleetwood Mac’s Tusk and Michael Jackson’s Bad. Those were all albums that were tasked with following up a monster critical and commercial smash; too much to expect of any mortal record.

However, what if The Kick Inside had never existed, and Lionheart had been her debut? Take away the baggage and the job of reviewing becomes a little more interesting.

Lionheart is not a perfect album yet its still a staggering achievement. Had it been the opening missive in Kate’s discography, jaws would have still dropped just as far. This record is a potent example of the complexity of Kate Bush and her audacious voice, charisma and songs. Had it been her debut, it may not have conferred upon her the instant mantle of “Icon” (as ‘Kick’ did), but that might have been a good thing.

Sure, Lionheart could have benefitted from more time in the bottle or… maybe not. Kate had all the time in the world to worry over The Dreaming. Was it a better record? I’ll let you know when I get around to listening to it as many times as I have Lionheart. Lionheart is a grower that is unique in her canon. Every track on Lionheart earns and rewards repeated visitations.

Let’s get the obvious out of the way. The song “Wow” is a wonderful confection of fantasy/pop. Equal parts torch ballad and bubblegum, it was a smart and successful single that could turn the heads of tabloid writers and music critics alike. And “England, My Lionheart”, is quite simply one of the most beautiful and unique melodies ever written. Usually in pop song craft you can hear echoes of the familiar; even if the artist is stealing from him/herself. This song exists on a different plane. That the lyrics are penned by a teenage girl is stupefying and magical. Why this song hasn’t been declared Britain’s national anthem is beyond me. It still might someday.

The epic “Hammer Horror” could be the subject of an entire review unto itself. By 1978, the term “Rock Opera” had become devalued currency. “Hammer Horror” is definitely a rock opera (albeit a tightly compressed and edited version of the form). Kate whispers, wails, moans and rumbles like both a siren and natural woman. She’s got some burr in her saddle in the form of a stalker, ex-boyfriend, ghost, or some unholy permutation of the three. Whatever happened, it’s now an ever-present nightmare of the soul. The tinkling piano ending turns the neat trick of being pretty and dissonant at the same time. The delayed reaction gong crash signals a melodramatic end to a brilliant and melodramatic record, and the cover art will rock your world.

Elsewhere, things get more eclectic and esoteric. “Coffee Homeground” courts Cabaret and Broadway and elevates both forms. Lead track, “Symphony In Blue” evokes a heavenly cocktail mix of Carol King on ecstasy and helium. On this album, even more than The Kick Inside, Kate takes her voice to its full, death defying limits. Many argue it takes listeners to their limits as well. Like Dylan, Kate’s voice is her signature, money maker, and albatross all rolled into one. One must come to the party prepared to marvel at her athleticism and then dig deep into the music itself. The rewards are there. Kate Bush is not a passive listen. We’ve got Sade for that. No, Lionheart is a three ring circus of emotion, estrogen and technique. And you know what? EMI put it out at just the right time. I’m glad we got two albums documenting Kate’s eloquent, teen dream genius. Soon our little girl would all grow up to be a woman. Lionheart didn’t do anything wrong, it’s just a matter of the paint on her masterpiece hadn’t quite dried yet” – The Muse Patrol

Standout Tracks: Wow, Kashka from Baghdad, Hammer Horror

Key Cut: Symphony in Blue

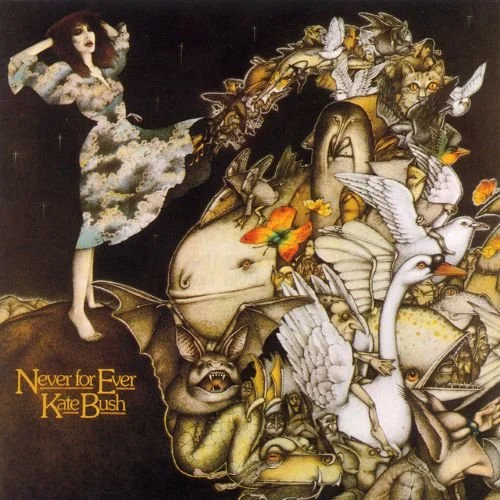

FOUR: Never for Ever (1980)

Release Date: 8th September, 1980

Review:

“The album opens with “Babooshka”, which reached number five on the UK Singles Chart. A classic story song—with a conflict, rising action, and eventual climax—it’s loosely based on the English folk song “Sovay”, which presents a tale of disguise, deception, and paranoia. A sinewy fretless bass stands in for the man in the story, weaving its way around the narrative as he approaches his incognito wife. When her trust has been broken, and his betrayal laid bare, the sound of breaking glass pierces the song at its climax, then trails off at its denouement.

Bush created the glass-breaking sound with the Fairlight CMI (as well as a few items from the Abbey Road kitchen), the revolutionary digital sampler introduced only a year earlier. She first saw the new instrument thanks to Peter Gabriel, when she sang backing vocals for his third eponymous album (known as Melt). The Fairlight’s impact on Bush’s creative process was profound: she was no longer tied to the piano and the decorative orchestral arrangements of her first two LPs. Rather, she could now write songs based on an infinite array of sonic textures. With the addition of other synthesizers — like the Yamaha CS-80 and the Prophet, as well as the Roland drum machine — she could create entire symphonies in a four-minute song. Bush had always used a menagerie of musical instruments, but the Fairlight freed her imagination. And, just like the mythical creatures flowing from beneath her skirt in the album’s cover illustration, once it was let loose, there was no going back.

It is on these songs, in particular, that listeners catch a glimpse of what’s to come. Tracks like “Delius”, with its dreamy and capacious soundscapes, are intermixed with tracks like “The Wedding List”, a sort of companion piece to “Babooshka”. With its dastardly narrative building to a dramatic chorus, “The Wedding List” is a showy vaudevillian number. But it relies on the conventional instruments and string arrangements of Bush’s earlier LPs and would have been at home on either one.

“Blow Away” and “All We Ever Look For” are sweet, sentimental songs that could also fit in the pre-Fairlight era. I particularly enjoy Kate’s voice on the latter, but the Fairlight samples of a door opening, Hare Krishna chanting, and footsteps seem to have been an afterthought. The samples add a narrative layer to the song, but the sounds are not integral to the arrangement.

“The Infant Kiss” is one of the highlights of the album, though it, too, is more of a throwback to earlier compositions. The eerie song was inspired by the film The Innocents, which was in turn based on the Henry James novella The Turn of the Screw. Lyrically, the song is similar to the title track of The Kick Inside and “The Man With the Child in His Eyes” in its dealing with taboo sexuality. The song’s narrator is a governess torn between the love of an adult man and child who inhabit the same body. Or, as one critic called it, “the child with the man in his eyes.”

What sets this song apart is Bush’s production. Instead of overwrought orchestral arrangements of the earlier albums, Bush relies on restrained, baroque instrumentation to convey the song’s conflicted emotions. With Bush behind the boards, she begins to use the studio as an instrument unto itself. Her growing technical facility, combined with the expansive possibilities of the Fairlight and other synthesizers, allowed her to express her feelings through sound more fully.

The penultimate “Army Dreamers” is a lamentation in the form of a waltz, sung from the viewpoint of a mother who’s lost her son in military maneuvers. Here, the samples of gun cocks add a percussive and forbidding element to the arrangement. The sound is restrained but menacing when coupled with the shouts of a commander in the background. Plus, “Army Dreamers” is one of the more political songs in Bush’s repertoire, though situating it inside a personal narrative keeps it from becoming polemical.

The album’s closer, “Breathing”, is a more overtly political song. It was Bush’s crowning achievement at the time, a realization of everything that had led her to this point. The song is told from a fetus’s perspective terrified of being born into a post-apocalyptic world: “I’ve been out before / But this time, it’s much safer in”. Bush plays on the words “fallout” and the rhythmic repetition of breathing—“out-in, out-in”—throughout.

Synthesizer pads and a fretless bass build to a middle section in which sonic textures take precedence over lyrical content, as Bush’s vocals fade to a false ending at the halfway mark. Ominous, atmospheric tones play over a spoken-word middle section describing the flash of a nuclear bomb. The male voice is chilling in its dispassionate delivery, and the bass comes to the foreground once again in a slow march to the finish as the song reaches its final dramatic crescendo. Here, Bush’s vocals, which admittedly can be grating at times, perfectly match the desperation of the lyrics. “Oh, leave me something to breathe!” she cries, in a terrifying contrast to Roy Harper’s monotone backing vocals (“What are we going to do without / We are all going to die without”).

“Breathing” is a full opera in five-and-a-half minutes, written, scored, arranged, and performed by an artist growing into herself and beginning to realize her full potential. It’s a fitting ending for Never for Ever, an album that sees Bush, only 23 years old at the time, leaving behind her ’70s juvenilia. At the turn of the 1980s, she was poised to scale new heights with her music, some of which would define the decade to come” – PopMatters

Standout Tracks: Babooshka, Army Dreamers, Breathing

Key Cut: The Wedding List

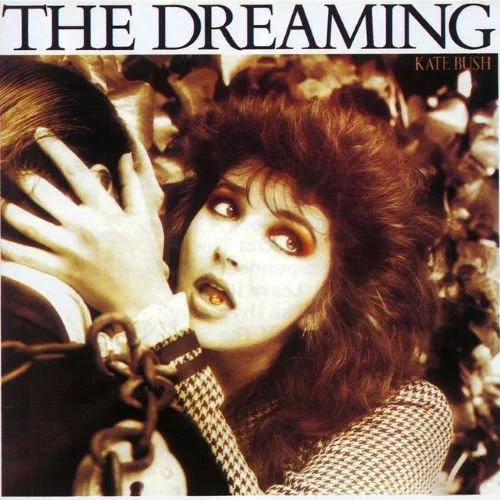

FIVE: The Dreaming (1982)

Release Date: 13th September, 1982

Review:

“The Dreaming really is more a product of the 1970s—which actually sort of began in the late ’60s and extended through most of the ’80s—when prog rock musicians sold millions, had huge radio hits, and established fan bases still rabid today. But the album also came out in 1982, and it only cemented the sense of Bush as a spirited, contrarian of Baroque excess in a musical moment defined largely in reaction to prog’s excess. It’s exactly that audacity to be weird against the prevailing trends that made Kate Bush a great feminist icon who expanded the sonic (and business) possibilities for subsequent visionary singer-songwriters. While name-checking Emerson, Lake & Palmer or Yes is relatively unheard of in today’s hip hop, indie, or pop landscapes, Kate Bush’s name was and is still said with respect. Perhaps it’s because unlike all those prog dudes of yore, she’s legibly, audibly very queer, and very obviously loves pop music, kind of like her patron saint, David Bowie.

On The Dreaming, Bush’s self-proclaimed “mad” album, her mind works itself out through her mouth. Her cacophony of vocal sounds—at least four on each track—pushed boundaries of how white pop women could sing. Everything about it went against proper, pleasing femininity. Her voice was too high: a purposeful shrilling of the unthreatening girlish head voice; too many: voices doubled, layered, calling and responding to themselves, with the choruses full of creepy doubles, all of them her; too unruly: pitch-shifted, leaping in unexpected intervals, slipping registers until the idea of femme and masculine are clearly performances of the same sounding person; too ugly: more in the way cabaret singers inhabit darkness without bouncing back to beauty by the chorus in the way that female pop singers often must.

All this excess is her sound: a strongly held belief that unites all of the The Dreaming. Nearly half of the album is devoted to spiritual quests for knowledge and the strength to quell self-doubt. Frenetic opener “Sat in Your Lap” was the first song written for the album. Inspired by hearing Stevie Wonder live, it serves as meta-commentary of her step back from the banality of pop ascendancy that mocks shortcuts to knowledge. A similar track, “Suspended in Gaffa,” laments falling short of enlightenment through the metaphor of light bondage in black cloth stagehand tape. It is a pretty queer-femme way of thinking through the very prog-rock problem of being a real artist in a commercial theater form, which is probably why it’s a fan favorite.

“Leave It Open” is a declaration of artistic independence hinging on the semantic ambiguity of its pronouns (what is “it” and who are “we”?). Here’s the one solid rock groove of the album, and it crescendos throughout while a breathy, heavily phased alto Bush calls and high-pitched Bush responds in increasingly frantic phrases. “All the Love” is the stunning aria of The Dreaming—a long snake moan on regret. Here she duets with a choirboy, a technique she’d echo with her son on 2011’s 50 Words for Snow. The lament trails off with a skipping cascade of goodbyes lifted from Bush’s broken answering machine, a pure playback memento mori.

The other half of the album showcases Bush’s talent for writing narratives about historical and imagined characters placed in unbearable moral predicaments. This is often called her “literary” or “cinematic” side, but it is also her connection to character within the Victorian-era British music hall tradition, a bawdy and comic form of working-class theatre that borrowed from American vaudeville traditions and became the dominant 19th- and early 20th-century commercial British pop art. As much as she’s in prog rock’s pantheon, she’s also part of this very-pre rock‘n’roll archive of cheeky musical entertainment.

When it works, her narrative portraits render precise individuals in richly drawn scenes—the empathy radiates out. In “Houdini” she fully inhabits the gothic romance of lost love, conjuring the panic, grief, and hope of Harry Houdini’s wife Bess. Bush was taken by Houdini’s belief in the afterlife and Bess’s loyal attempts reach him through séances. Bush conjured the horrified sounds of witnessing a lover die by devouring chocolate and milk to temporarily ruin her voice. Bess was said to pass a key to unlock his bonds through a kiss, the inspiration for the cover art and a larger metaphor for the depth of trust Bush wants in love. We must need what’s in her mouth to survive, and we must get it through a passionate exchange among willing bodies.

In her borrowing further afield, her characters are less accurately rendered. This has been an unabashedly true part of Bush’s artistic imagination since The Kick Inside’s cover art, vaguely to downright problematic in its attempts to inhabit the worlds of Others. On “Pull Out the Pin” she uses the silver bullet as a totem of one’s protection against an enemy of supernatural evil. In this case, the hero is a Viet Cong fighter pausing before blowing up American soldiers who have no moral logic for their service. She’d watched a documentary that mentioned fighters put a silver Buddha into their mouths as they detonated a grenade, and in that she saw a dark mirror to key on the album cover. While the humanizing of such warriors in pop narrative is a brave act, it’s also possible to hear her thin arpeggiated synth percussion and outro cricket sounds as a part of an aural Orientalism that undermines that very attempt.

Then there’s “The Dreaming,” a parable of a real, historical, and contemporary group of Aboriginal people as timeless, noble savages in a tragically ruined Eden that lectures the center of empire about their (our) political and environmental violence. Bush narrates in a grotesquely exaggerated Australian accent over a thicket of exotic animal sounds, both holdovers from music hall and vaudeville’s racist “ethnic humor” tradition, a kind of distancing that suggests that settler Australians are somehow less civilized and thus more responsible for their white supremacist beliefs than the Empire that shipped them there in the first place. In telling this story in this way—without accurate depictions of people, and without credit, understanding, monetary remuneration, proper cultural context, or employment of indigenous musicians—she unfairly extracts cultural (and economic) value from Aboriginal suffering just as the characters in the song mine their land. As a rich text to meditate on colonial, racial, and sexual violence, it is actually quite useful—but not in the way Bush intended.

The closer “Get Out of My House” was inspired by two different maternal and isolation-madness horror texts: The Shining and Alien. In all three stories, a malevolent spirit wants to control a vessel. Bush does not let the spirit in, shouts “Get out!” and when it violates her demand, she becomes animal. Such shapeshifting is a master trope in Kate Bush’s songbook, an enduring way for her music and performance to blend elements of non-Western spirituality and European myth, turning mundane moments into Gothic horror. It’s also, unfortunately, the way that women without power can imagine escape. The mule who brays through the track’s end is a kind of female Houdini—a sorceress who can will her way out of violence not with language, but with real magic. At least it works in the world of her songs, a kingdom where queerly feminine excess is not policed, but nurtured into excellence” – BBC

Standout Tracks: Sat in Your Lap, Night of the Swallow, Get Out of My House

Key Cut: Houdini

TWO: Hounds of Love (1985)

Release Date: 16th September, 1985

Review:

“Kate Bush's strongest album to date also marked her breakthrough into the American charts, and yielded a set of dazzling videos as well as an enviable body of hits, spearheaded by "Running Up That Hill," her biggest single since "Wuthering Heights." Strangely enough, Hounds of Love was no less complicated in its structure, imagery, and extra-musical references (even lifting a line of dialogue from Jacques Tourneur's Curse of the Demon for the intro of the title song) than The Dreaming, which had been roundly criticized for being too ambitious and complex. But Hounds of Love was more carefully crafted as a pop record, and it abounded in memorable melodies and arrangements, the latter reflecting idioms ranging from orchestrated progressive pop to high-wattage traditional folk; and at the center of it all was Bush in the best album-length vocal performance of her career, extending her range and also drawing expressiveness from deep inside of herself, so much so that one almost feels as though he's eavesdropping at moments during "Running Up That Hill." Hounds of Love is actually a two-part album (the two sides of the original LP release being the now-lost natural dividing line), consisting of the suites "Hounds of Love" and "The Ninth Wave." The former is steeped in lyrical and sonic sensuality that tends to wash over the listener, while the latter is about the experiences of birth and rebirth. If this sounds like heady stuff, it could be, but Bush never lets the material get too far from its pop trappings and purpose. In some respects, this was also Bush's first fully realized album, done completely on her own terms, made entirely at her own 48-track home studio, to her schedule and preferences, and delivered whole to EMI as a finished work; that history is important, helping to explain the sheer presence of the album's most striking element -- the spirit of experimentation at every turn, in the little details of the sound. That vastly divergent grasp, from the minutiae of each song to the broad sweeping arc of the two suites, all heavily ornamented with layered instrumentation, makes this record wonderfully overpowering as a piece of pop music. Indeed, this reviewer hadn't had so much fun and such a challenge listening to a new album from the U.K. since Abbey Road, and it's pretty plain that Bush listened to (and learned from) a lot of the Beatles' output in her youth” – AllMusic

Standout Tracks: Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God), Hounds of Love, Jig of Life

Key Cut: The Big Sky

SIX: The Whole Story (1986)

Release Date: 10th November, 1986

Review:

“The Whole Story takes the listener away on a musical ride through some of Bush’s most iconic moments from the beginning of her career. Hearing Bush’s early work in particular showcases the evolution of her wonderfully wavy vocals and wild imagination. From her softly sung piano ballad ‘The Man With The Child In His Eyes’, written at the age of just fourteen, to her spacey-orchestral experiment track ‘Wow’, taken from her second album Lionheart.

Bush uses The Whole Story to really showcase the formation of her now trademark quirkiness. With tracks like ‘Babushka’, (about a woman romantically fooling her husband) and the iconic pop anthem ‘Running Up That Hill (A Deal With God)’, being flawless demonstrations of her ability to continually surprise listeners and push boundaries. Every track on The Whole Story shows the pure creativity and song-writing talent possessed by Bush – a skill heard in every one of her song’s piano notes and every drum beat.

Opening this compilation is the genius ‘Wuthering Heights’, which Bush remixed and re-recorded herself for this project. This remixing was done purely with the intent on giving the song a more mature sound, replacing Bush’s original vocals for the track when it was released in 1978, when Bush was just 19. This minor alteration in sound really does highlight the subtle change in vocal depth and resonance Bush developed in the eight years between the original track release to the polished and perfected iteration heard on The Whole Story.

Kate Bush creates magical worlds through her music, vocals and lyrics that has the fantastic ability to transport you away to a wondrous place where anything could happen. A place where Catherine and Heathcliff are together; a place where God will let you be another person to escape from the excruciating feeling of loving someone too much. The Whole Story is a vessel that ultimately transports the listener to the depths of Kate Bush’s imagination.

Kate Bush is not a singer, she is an artist. In fact, she is one of the most important artists of our time, and one that will continue to shape the music industry forever. Listening to The Whole Story is all the proof you need. 10/10” – Mancunion

Standout Tracks: The Man with the Child in His Eyes, Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God), Experiment IV

Key Cut: Hounds of Love

ONE: The Sensual World (1989)

Release Date: 16th October, 1989

Review:

“The Sensual World is not a work of po-faced realism or post-Neverland dowdiness. Bush sings about falling in love with a computer, dressing up as a firework, and dancing with a dictator. She’s still in thrall to love, lust, loneliness, passion, pain, and pleasure. And she’s still fond of strange noises; listen closely to the title track and you might hear her brother, Paddy, swishing a fishing rod through the air.

But she’d never sounded more grounded than she did on these 10 songs, most of which are about regular people in regular messes, not disturbed governesses, paranoid Russian wives or terrified fetuses. It was, she said, her most honest, personal album, and its stories play out like intimate vignettes rather than fantastical fairy tales. Unlike the otherworldly synth-pop-prog she pioneered on 1985’s Hounds of Love, she used her beloved Fairlight CMI to produce lusher, mellow textures, complemented by the warm, earthy thrum of Irish folk instruments and the pretty violins and violas of England’s classical bad boy, Nigel Kennedy. Even the album’s artwork depicted a less playful, more serious Bush than the one who’d fondled Harry Houdini on 1982’s The Dreaming and cuddled dogs on Hounds of Love.

There’s no Hounds-style grand narrative thread on The Sensual World. Bush likened it to a volume of short stories, with its subjects frequently wrestling with who they were, who they are, and who they want to be. She was able to pour some of her own frustrations into these knotty tussles: She found it more difficult than ever to write songs, couldn’t work out what she wanted them to say, and hit roadblock after roadblock. The 12 months she spent pestering Joyce’s grandson were surpassed by the maddening two years she spent on “Love and Anger,” which, fittingly, finds her tormented by an old trauma she can’t bring herself to talk about. But by the end, she banishes the evil spirits by leading her band in something that sounds like a raucous exorcism, chanting, “Don’t ever think you can’t change the past and the future” over squalling guitars.

Even its most surreal songs are rooted in self-examination. “Heads We’re Dancing” seems like a dark joke—a young girl is charmed on to the dancefloor by a man she later learns is Adolf Hitler—but poses a troubling question: What does it say about you, if you couldn’t see through the devil’s disguise? Its discordant, skronky rhythms make it feel like a formal ball taking place in a fever dream, and Bush’s voice grows increasingly panicky as she realizes how badly she’s been duped. As far-fetched as its premise was, its inspiration lay close to home: A family friend had told Bush how shaken they’d been after they’d taken a shine to a dashing stranger at a dinner party, only to find out they’d been chatting to Robert Oppenheimer.

It’s more fanciful than most of The Sensual World’s little secrets. To hear someone recall formative childhood truths (the lush grandeur of “Reaching Out”) and lingering romantic pipedreams (the longing of “Never Be Mine”) is like being given a reel of their memory tapes and discovering what makes them tick. On “The Fog,” she’s paralyzed by fear until she remembers the childhood swimming lessons her father gave her, his voice cutting through the misty harps like an old ghost. Relationships on the album can be sticky and thorny. “Between a Man and a Woman” is half-dangerous and half-sultry, its snaking rhythms mirroring the round-in-circles squabbling of a couple. When a third party tries to interfere, they’re told to back off. This time, unlike on “Running Up That Hill (A Deal With God),” there’s no point wishing for a helping hand from God.

But if there are no miracles, there are at least songs that sound like them. For “Rocket’s Tail,” Bush enlisted the help of Trio Bulgarka, who she fell in love with after hearing them on a tape Paddy gave her. The three Bulgarian women didn’t speak English and had no idea what they were singing about, but it didn’t matter. They sound more like mystics during its a capella first half, and when it eventually blows up into a glammy stomper with Dave Gilmour’s electric guitar caterwauling like a Catherine wheel, their vocals still come out on top: cackling like gleeful witches, whooping like they’re watching sparks explode in the night sky. Its weird, wonderful magic offered a simple message: Life is short, so enjoy moments of pleasure before they fizzle out.

Perhaps that’s why there are glimmers of hope even in the album’s most desperate circumstances. “Deeper Understanding” is a bleak sci-fi tale about a lonely person who turns to their computer for comfort, and in doing so isolates themselves even more. But while there’s an icy chill to the verses, Trio Bulgarka imbue the computer’s voice with golden warmth. Bush wanted it to sound like the “visitation of angels,” and hearing the chorus is like being wrapped in a celestial hug. She pulls off a similar trick on “This Woman’s Work,” which she wrote for John Hughes’ film She’s Having a Baby, although her vivid, devastating interpretation of its script has taken on a far greater life of its own. It captures a moment of crisis: a man about to be walloped with the sledgehammer of parental responsibilities, frozen by terror as he waits for his pregnant wife outside the delivery room, his brain a messy spiral of regrets and guilty thoughts. Yet Bush softens the song’s building panic attack with soft musical touches so it rushes and swirls like a dream, even as reality becomes a waking nightmare. “It’s the point where has to grow up,” said Bush. “He’d been such a wally.”

She didn’t need to prove her own steeliness to anyone, especially the male journalists who patronized her and harped on her childishness as a way of cutting her down to size. Instead, The Sensual World is the sound of someone deciding for themselves what growing up and grown-up pop should be, without being beholden to anyone else’s tedious definitions. It gave her a new template for the next two decades, inspiring both the smooth, stylish art-rock of 1993’s The Red Shoes and the picturesque beauty of 2005’s Aerial. Like Molly Bloom, Bush had set herself free into a world that wasn’t mundane, but alive with new, fertile possibility” – Pitchfork

Standout Tracks: The Sensual World, Never Be Mine, This Woman’s Work

Key Cut: The Fog

NINE: The Red Shoes (1993)

Release Date: 1st November, 1993

Review:

“The most powerful moments on The Red Shoes are its most intimate and personal. ‘Moments Of Pleasure’ starts with piano so soft and gentle it feels like it might vanish if you breathe too hard, before it’s swept up in Michael Kamen’s elegantly soul-stirring orchestral arrangement. Bush’s voice goes through a similar transformation, too, growing from a gentle flutter to something stronger, which makes her heartfelt cry on the chorus sound like a defiant refusal to be swallowed by grief: “Just being alive/ It can really hurt/ And these moments/ Are a gift from time.” Its outro remembers some of Bush’s lost friends – including guitarist Alan Murphy, producer John Barrett and lighting director Bill Duffield – and plays out like the closing credits of an old-fashioned weepy. Even more devastating is an old conversation she recalls with her mother, Hannah, who was ill while Bush was writing the song and who passed away before the album was released. “I can hear my mother saying ‘Every old sock needs an old shoe,’” remembers Bush warmly. “Isn’t that a great saying?” It is, even if it sticks a tennis ball-sized lump in your throat.

There’s emotional heft on ‘Top Of The City’, too, which takes a similar premise to ‘And So Is Love’ but adds higher stakes: Bush sits up in the skies, looking down at the lonely city below and hoping to find an answer. “I don’t know if I’m closer to Heaven, but it looks like Hell down there,” she declares, caught between exhilaration, melancholy and desperation: the moments of quiet calm are both beautiful and unsettling, with eerie pockets of silence hanging between delicate piano notes, until there’s a big, dramatic burst of violins and celestial backing vocals. “I don’t know if you’ll love me for it,” she yells wildly, forcing the moment to its crisis. “But I don’t think we should suffer for this/ There’s just one thing we can do about it.”

As heart-rending as those two tracks are, the simplicity of The Red Shoes can be endearingly playful. In 2o11, Bush called the happy-go-lucky ‘Rubberband Girl’, with its twanging guitars and parping trombones and trumpets, a “silly pop song”: she’s right, and the reason it spreads so much contagious joy is because you can tell she and her band are having such a ball, especially when she wails “rub-a-dub-dub” and makes her voice wobble and vibrate like a boinging bungee cord. The calypso-flavoured ‘Eat The Music’, which features Malagasy musician Justin Vali on the valiha and the kabosy, is equally fun, as Bush puts a new spin on the idea of getting fruity with a lover. “Let’s split him open, like a pomegranate,” she chants. “Insides out/ All is revealed.” “I wanted it to feel joyous and sunny, both qualities are rife in Justin as a person,” said Bush, who met Vali through her brother Paddy. “I just had to provide the fruit.”

Hearing her equate emotional intimacy with scoffing mangoes and plums might suggest that The Red Shoes still has plenty of idiosyncrasies. There’s certainly something quintessentially Bushian about some of its songs, including the title cut, which soundtracks the fate of a girl who puts on a pair of red leather ballet shoes and dances a frantic Irish jig: it combines her fondness for Celtic sounds, old stories and classic film (The Red Shoes was written by Hans Christian Andersen and later adapted into a 1948 film directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, the former of whom Bush salutes on ‘Moments Of Pleasure’), and her shrill, possessed vocal makes it sound like a feverish fairytale. The steamy ‘The Song Of Solomon’, meanwhile, mixes a literary text and desire in the same way that ‘The Sensual World’ let Ulysses’ Molly Boom step off the page and experience physical pleasure. This time, there was no-one stopping Bush lifting lines from her chosen book, the Hebrew Bible, although the erotic charge of the chorus is all hers: “Don’t want your bullshit, yeah/ Just want your sexuality.”

And if Bush has dabbled with the gothic and supernatural ever since ‘Wuthering Heights’, there’s more magick on the moody, witch-rock of ‘Lily’, a tribute to her friend and spiritual healer, Lily Cornford. “I said ‘Lily, oh Lily, I’m so afraid,’” trembles Bush. “I fear I am walking in the vale of darkness.” She banishes the evil spirits with fire and the help of four angels, although Gabriel, Raphael, Michael and Uriel couldn’t save The Line, The Cross And The Curve, the Bush-directed film-meets-visual-album which included videos for ‘Lily’ and five of the LP’s other songs. Inspired by Powell’s original movie, the singer is tricked by Miranda Richardson into wearing the cursed ballet slippers, and must free herself from the curse under the tutelage of Lindsay Kemp. It was, Bush later claimed, a “load of old bollocks”.

It’s easy enough to find the common thread running through The Red Shoes: time and time again she returns to being brave, to being strong, to being open, to having to decide between holding on or letting go, and still trusting you’ll come out OK on the other side. There is, admittedly, less of a sonic coherence, especially in its latter stages. ‘Constellation Of The Heart’ is a colourful swirl of funky guitars, organs and saxophone, while ‘Big Stripey Lie’ is built upon Nigel Kennedy’s gorgeous violin but is undercut by bitty guitars and discordant squiggles of noise, its scorched beauty hinting at violent chaos as Bush frets: “Oh my god, it’s a jungle in here.”

That’s then followed by the absurdity of ‘Why Should I Love You?’ Bush had originally asked Prince to record backing vocals for the track, but he decided to take it apart and add guitars, keyboards and brass, too. Conventional wisdom is that great collaborations are the result of a shared vision, but ‘Why Should I Love You?’ is great even though there’s absolutely no shared vision whatsoever: for the first 60-odd seconds it’s built around Bush’s hushed vocal, until Prince’s huge rush of ecstatic, kaleidoscopic sound steamrolls everything in its path. It’s less the meeting of two minds and more the smashing together of two completely different styles, the most special of cut-and-shunt hybrids. (And somewhere, among all the hullabaloo, you’ll also hear backing vocals from Lenny Henry).

There’s another cameo on the closing song, the fantastically histrionic breakup ballad ‘You’re The One’, on which Jeff Beck’s dizzying, drawn-out guitar solo pushes Bush to an exhausting catharsis. Like so much of The Red Shoes, it finds her preparing to leave a lover to save herself, although this time she’s less bullish, more prone to tying herself in knots. “I’m going to stay with my friend/ Mmm, yes, he’s very good-looking,” she admits. “The only trouble is, he’s not you.” By the song’s end, she’s so frazzled by frustration and anguish that she lets rip a larynx-tearing shriek: “Just forget it, alright!” Bush, who had spoken of feeling emotionally burnt-out years before the album was released, was ready to withdraw, too: she vanished for 12 years until Aerial, and then went on hiatus for another six before returning with Director’s Cut. “I think there’s always a long, lingering dissatisfaction with everything I’ve done,” she said in 2011, glad to have the chance to right some of the wrongs that had been bothering her for 20-odd years. For me, though, the original album has always been enough: it might have its flaws, and there might be a handsome alternative, but just like Bush on ‘You’re The One’, I still want to keep going back” – The Quietus

Standout Tracks: Eat the Music, Moments of Pleasure, The Red Shoes

Key Cut: Rubberband Girl

ELEVEN: Aerial (2005)

Release Date: 7th November, 2005

Review:

“These days, record companies try to make every new album seem like a matter of unparalleled cultural import. The most inconsequential artists require confidentiality agreements to be faxed to journalists, the lowliest release must be delivered by hand. So it's hard not to be impressed by an album that carries a genuine sense of occasion. That's not to say EMI - which earlier this year transformed the ostensibly simple process of handing critics the Coldplay album into something resembling a particularly Byzantine episode of Spooks - haven't really pushed the boat out for Kate Bush's return after a 12-year absence. They employed a security man specifically for the purpose of staring at you while you listened to her new album. But even without his disconcerting presence, Aerial would seem like an event.

In the gap since 1993's so-so The Red Shoes, the Kate Bush myth that began fomenting when she first appeared on Top of the Pops, waving her arms and shrilly announcing that Cath-ee had come home-uh, grew to quite staggering proportions. She was variously reported to have gone bonkers, become a recluse and offered her record company some home-made biscuits instead of a new album. In reality, she seems to have been doing nothing more peculiar than bringing up a son, moving house and watching while people made up nutty stories about her.

Aerial contains a song called How to Be Invisible. It features a spell for a chorus, precisely what you would expect from the batty Kate Bush of popular myth. The spell, however, gently mocks her more obsessive fans while espousing a life of domestic contentment: "Hem of anorak, stem of wallflower, hair of doormat."

Domestic contentment runs through Aerial's 90-minute duration. Recent Bush albums have been filled with songs in which the extraordinary happened: people snogged Hitler, or were arrested for building machines that controlled the weather. Aerial, however, is packed with songs that make commonplace events sound extraordinary. It calls upon Renaissance musicians to serenade her son. Viols are bowed, arcane stringed instruments plucked, Bush sings beatifically of smiles and kisses and "luvv-er-ly Bertie". You can't help feeling that this song is going to cause a lot of door slamming and shouts of "oh-God-mum-you're-so-embarrassing" when Bertie reaches the less luvv-er-ly age of 15, but it's still delightful.

The second CD is devoted to a concept piece called A Sky of Honey in which virtually nothing happens, albeit very beautifully, with delicious string arrangements, hymnal piano chords, joyous choruses and bursts of flamenco guitar: the sun comes up, birds sing, Bush watches a pavement artist at work, it rains, Bush has a moonlight swim and watches the sun come up again. The pavement artist is played by Rolf Harris. This casting demonstrates Bush's admirable disregard for accepted notions of cool, but it's tough on anyone who grew up watching him daubing away on Rolf's Cartoon Club. "A little bit lighter there, maybe with some accents," he mutters. You keep expecting him to ask if you can guess what it is yet.

Domestic contentment even gets into the staple Bush topic of sex. Ever since her debut, The Kick Inside, with its lyrics about incest and "sticky love", Bush has given good filth: striking, often disturbing songs that, excitingly, suggest a wildly inventive approach to having it off. Here, on the lovely and moving piano ballad Mrs Bartolozzi, she turns watching a washing machine into a thing of quivering erotic wonder. "My blouse wrapping around your trousers," she sings. "Oh, and the waves are going out/ my skirt floating up around my waist." Laundry day in the Bush household must be an absolute hoot.

Aerial sounds like an album made in isolation. On the down side, that means some of it seems dated. You can't help feeling she might have thought twice about the lumpy funk of Joanni and the preponderance of fretless bass if she got out a bit more. But, on the plus side, it also means Aerial is literally incomparable. You catch a faint whiff of Pink Floyd and her old mentor Dave Gilmour on the title track, but otherwise it sounds like nothing other than Bush's own back catalogue. It is filled with things only Kate Bush would do. Some of them you rather wish she wouldn't, including imitating bird calls and doing funny voices: King of the Mountain features a passable impersonation of its subject, Elvis, which is at least less disastrous than the strewth-cobber Aussie accent she adopted on 1982's The Dreaming. But then, daring to walk the line between the sublime and the demented is the point of Kate Bush's entire oeuvre. On Aerial she achieves far, far more of the former than the latter. When she does, there is nothing you can do but willingly succumb” – The Guardian

Standout Tracks: How to Be Invisible, A Coral Room, Aerial

Key Cut: Mrs Bartolozzi

EIGHT: Director’s Cut (2011)

Release Date: 16th May, 2011

Review:

“Kate Bush has earned the privilege of working in geological time. She was once a pop star who turned out landmark releases relatively quickly, but now, aeons pass between releases.

Six years have gone since Aerial, her last, double album; before that, 12 years went by with barely an aerated hiccup. Bush makes you wait, and nothing is more tantalising in an age of instant-everything-on-demand than not hearing from an adored artist. Bush has not toured since 1979, an artistic quirk that has some bearing on Director's Cut.

One further reason the reclusive 52-year-old mum-of-one is a rare nightingale among starlings is that she is a fully paid-up geek – inhabiter of her own home studio, early adopter of all sorts of recording technology, and au fait with the intimidating gizmos that keep most artists enslaved to producers. She might have caught the public's eye in the late 70s as a wild-eyed warbler in a leotard, and cemented her reputation in the 80s as an arch-sensualist, but Bush is a girl who knows her way around gear.

Only a nerd of the deepest hue would bother to painstakingly transpose her 1993 album, The Red Shoes, from its digitally produced final cut into analogue tracks, held by many audiophiles to be "warmer"-sounding. This is precisely what Bush has done on Director's Cut. The album takes great swathes of The Red Shoes and choice cuts from its predecessor, 1989's The Sensual World, and reworks them, sometimes with subtlety, and sometimes with daring.

The most high-profile edit concerns the title track of The Sensual World. Bush originally intended to use Molly Bloom's climactic speech from James Joyce's Ulysses as her lyric, but Joyce's estate denied her the privilege. With that decision reversed, the resulting track – now retitled "Flower of the Mountain" – is a fascinating restoration.

Bush has seriously messed with "Deeper Understanding" as well, a track whose prescience about the siren's call of the internet is shivery. The computer gets a bigger voice – Bush's 12-year-old son, Bertie – and a dose of Auto-Tune, the vocal effect of choice of 21st-century R&B. It will make you smile. So will Bush cutting loose on "Lily".

Throughout, Bush's youthful gasps have gone, replaced by the purr of an older woman. What the songs have lost in urgency they have gained in calm, not always for the better. One of Bush's most sacred texts, "This Woman's Work", will be Bush's most controversial reinterpretation. It's bare, orchestrated with bell-like keys and a little thrum that pans between headphones so as to make you dizzy. Her new vocal is magical, but where once the whole track reverberated with emotion, there is now a wafty ambient tonality reminiscent of new age treatment rooms.

Director's Cut finds Bush satisfying her own internal urge to mend rather than make do. And while most of us may find such obsessive revisionism baffling, it still makes for a beguiling album. You can't help but wonder though: had Bush worked over her old songs in live shows rather than in the studio, might we have had a new album by now?” – The Guardian

Standout Tracks: Lily, This Woman’s Work, And So Is Love

Key Cut: Top of the City

TWELVE: 50 Words for Snow (2011)

Release Date: 21st November, 2011

Review:

“So yeah: maybe when Kate Bush said the 12 year gap between The Red Shoes and Aerial was down to her wanting to work on being a mum for a while – and not because she’d had a mental breakdown/become morbidly obese/was a dope fiend/sundy other conspiracy theories that flew around – she was, y’know, telling the truth. Here, six years after Aerial and just six months after Director’s Cut comes 50 Words for Snow. It’s Bush’s third album since 2005, which technically puts her up on The Strokes, The Shins or Modest Mouse.

And jolly spectacular it is too, which is never a guarantee: Aerial was a masterpiece; The Red Shoes, The Sensual World and the diversionary Director’s Cut were not. Bush has always been best at her most focussed, and here she delves monomaniacally into snow and the winter – its mythology, its romance, its darkness, its rhythmic frenzy and glacial creep. 50 Words for Snow is artic and hoare frost and robin red breast, sleepy snowscapes and death on the mountain, drifts in the Home Counties and gales through Alaska.

But it is mostly, I think, a record about how the fleeting elusiveness of snow mirrors that of love; and if I’m off the mark there, then certainly as a work of music one can view it as a sort of frozen negative to Aerial’s A Sky of Honey, the transcendent 42 minute suite about a summer’s day that took up the album’s second half. Whatever the case, 50 Words...demands to be listened to as a whole: the days of Bush as a singles-orientated artist are long gone on a long, sometimes difficult record on which the shortest track clocks in at a shade under seven minutes.

The first three songs clock in at over half an hour and comprise the starkest, most difficult and in some ways most beautiful passage of music in Bush’s career. Based on minimal, faltering piano and great yawning chasms of silence, these tracks mirror the eerie calm of soft, implacable snowfall and winter's dark. On the opening ‘Snowflake’ she shares vocal duties with her young son Albert, whose pure falsetto blends into her lower register. Vaguely suggestive of carol singing, his tones are also clear and elemental, without the shackles of adult emotion as he keens “I am ice and dust and light. I am sky and here.” over his mother’s spare, hard keys. ‘Lake Tahoe’ is the real challenge here: a crawling ghost story about a drowned woman, gilded with cold choral washes, its diamond keys crystallize into being a note at a time. Its 11 minutes are roughly as far away from ‘Babooshka’ as it’s possible to get. Yet as Steve Gadd’s soft, jazzy drums gather in pace and intricacy, life and movement enters this crepsular musical tundra, the album’s low key opening sequence swelling to a soft crescendo with final part ‘Misty’. A bleakly sensual love story that, er, appears to be about a doomed affair with a snowman, it’s somewhat reminiscent of Spirit of Eden-era Talk Talk as its 13-minute expanse periodically blooms into gorgeously tangled blossoms of bucolic guitar.

Single ‘Wild Man’ sees a shift in gear – springy, exotic electronics, a sprightlier pace and a sense of playfulness as a husky-voiced Bush trades the last song’s impossible man for another as she dreams about the possibility of a yeti. Describing a Kate Bush track without making it sound silly can be rather trying – this is a woman whose past triumphs include several songs featuring Rolf Harris – but I guess ‘Wild Man’ works as lush, sensual dream of the possibility of the things that might existing outside humdrum human experience. It’s not just about the yeti, but the impossibly exotic place names she mutters in her verbal quest for the creature – “Kangchenjunga… Metoh-Kangmi… Lhakpa-La… Dipu Marak… Darjeeling… Tengboche… Qinghai… Himachal Pradesh” – and the vertiginously thrilling change of gear as heavily distorted guest Andy Fairweather Low roars a near indecipherable chorus. It’s also about Bush’s formidable production skills, her precise, nagging synths and total mastery of studio as instrument.

Those synths imbue ‘Snowed in at Wheeler Street’ with a sense of frazzled foreboding that negates the potential cheesiness of Elton John’s throaty turn on a duet that casts him and Bush as a pair of lovers spread across time, doomed to separate at key points in history, wishing that could return to one mundane, snow bound day spent together. And a bed of electronics whip up a quietly hypnotic tumult on the astonishing title song. Here – and again Kate Bush songs can be a job to not make sound ridiculous – Bush counts to 50 in a hushed monotone as Stephen Fry (oh yes) recites a list of names for snow, real and imagined: “blackbird braille… stella tundra… vanilla swarm… avalanche”, occasionally punctured by an eerily muted chorus in which Bush frenzied urges him to continue the list. On the one hand, it continues ‘Wild Man’s revelry in the intoxicating power of human language. On the other, it’s the album’s least human track, its churning, chiming electronics and alien words mirroring the quiet chaos and leaden intensity of a snowstorm, its final minutes a headlong descent into oblivion and whiteout. It is astonishing, immense, bizarre and perfectly realized: only Kate Bush could conceive of this song, and nobody else will make anything like it again.

As the cooing over Director’s Cut demonstrated, even Bush on diversionary form is enough to tease gushy spurts of adjectives from the soberest of souls; hitting a true peak again, there is the temptation to drone on about how important she is, how she dwarfs most of her peers artistically, let alone the braying yahs and rahs of today who cite her as an influence. But let’s keep it in perspective: in the 26 years since Hounds of Love, Aerial and 50 Words for Snow have been her only truly fully realised albums. Kate Bush is more than fallible; but at peak she is incomparable. 9” – Drowned in Sound

Standout Tracks: Snowflake, Wild Man, Among Angels

Key Cut: Misty

SEVEN: Before the Dawn (2016)

Release Date: 25th November, 2016

Review:

“Some of the shows were filmed, but so far there has been no word of a DVD or cinematic release. Perhaps the rigours of transferring stage magic to screen gold proved too exacting. Instead, after a cooling-off period of two years, Before The Dawn is presented as a purely musical experience. Released as download, triple-CD and quadruple vinyl, this live album documents the entire show, in sequence. For those invested in the historic drama surrounding Bush’s return to live performance, it’s a godsend. For those less committed souls, it may present some challenges.

You could certainly spend time grumbling about what this album *isn’t*. It’s definitively not Kate Bush exploring all corners of her criminally underperformed catalogue. Nothing here pre-dates 1985, and the vast majority of the 27 songs are taken from just two albums: Hounds Of Love and Aerial, alongside one each from The Sensual World and 50 Words For Snow, and two from The Red Shoes. A new song, “Tawny Moon”, is slotted into A Sky Of Honey, and it’s good, a churning, mechanical piece of modern blues, sung gamely by Bush’s teenage son Bertie McIntosh.

Rather than present one full show in its entirety, Bush has chosen to stitch together performances from throughout the run. This allows for the inclusion of a wonderful rehearsal version of “Never Be Mine”, a piece of pastoral ECM restored to the running order after being dropped at the eleventh hour. It appears during Act One, the part of Before The Dawn which most resembles a conventional concert. This is the opening seven-song sequence where Bush ticks off some hits and performs them straight.

The rolling rhythm and quicksilver synthetic pulse of “Running Up That Hill” is beautifully realised, while a rapturous “Hounds Of Love” locates the taut, wolverine snap of the original. She toys with the chorus melody, throwing in a Turner-esque entreaty to “tie me to the mast”, a measured tinkering in keeping with the prevailing musical sensibility. Bush, the ultimate studio artist, opts for faithful reproductions of her oeuvre with just a few twists. Nothing has been re-recorded or overdubbed; presumably there was no need. The band of stellar sessionmen are supple, empathetic and meticulous, as is the Chorus of supporting actors and singers recruited mainly from musical theatre. Among their ranks young Bertie, only 16 at the time, does a remarkably proficient job.

Bush’s voice remains a wonder. These days it’s deeper and huskier, cross-hatched with bluesy ululations and soulful stylings. On the opening “Lily”, she sings like a lioness, drawing sparks from the words “fire” and “darkness” over a thick, plush groove. During a terrifically showbizzy “Top Of The City”, she rises from a serene whisper to a banshee howl. Riding the chimeric reggae of “King Of The Mountain” she transitions from sensuous earth mother to lowering Prospero, summoning the tempest during the tumultuous, drum-heavy, propulsive climax.

This is a key moment in Before The Dawn, a hinge between the straight gig and the theatrics which follow. From now on, listening to the album is sometimes akin to hearing the soundtrack to a film being screened in another room. Act Two, The Ninth Wave, is particularly tricky in this regard. The conceptual suite about a woman lost at sea after a ship sinks lends itself to a sustained visual experience, but has to work harder on record. At Hammersmith, “Hello Earth” was staggeringly operatic, as dramatic and contemporary as any modern staging of The Ring or Parsifal. Here, it is merely – *merely* – a magnificent piece of music.

The encores wheel back to the show’s no-concept beginnings. She sings “Among Angels” alone at the piano. Almost unspeakably intimate, it’s a timely reminder that, for all the theatrics, if Bush were ‘just’ a singer she would still be utterly remarkable. This is followed by a celebratory “Cloudbusting” – another of her classics which you suddenly realise you’ve never heard performed live, whether by Bush or anybody else – which sounds like the best kind of circus music. Long and loose, it’s a musical smile, “like the sun coming out”. And then it’s over.

At the start of Before The Dawn, after the rousing crowd response to “Lily”, Bush chirps, “Oh thank you, what a lovely welcome!” She says little else until the end of “Cloudbusting” when, clearly moved, she exclaims, “Oh my God! What a beautiful sight! Look at you all, I will always remember this.” Above all else, the album seems to seek to honour that sentiment, a physical testament to an extraordinary shared moment between artist and audience.

There may be an argument for excising the dramatic interludes, and perhaps even a handful of songs, in favour of something leaner and more sculpted. But that would be to bind Bush to the conventions she has spent an entire career challenging, and to misunderstand the ambition and intention behind Before The Dawn. What we have instead is an exhaustive audio souvenir of a momentous event, simply to remind us – and perhaps Bush, too – that it really did happen after all” – The Guardian

Standout Tracks: Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God), Hello Earth, Nocturn

Key Cut: And Dream of Sheep