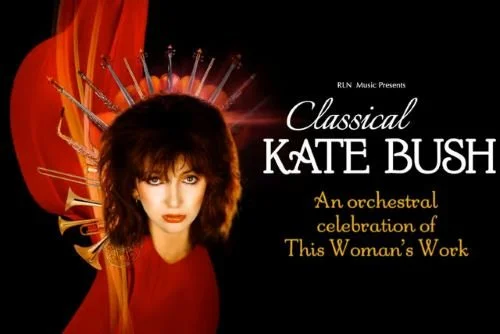

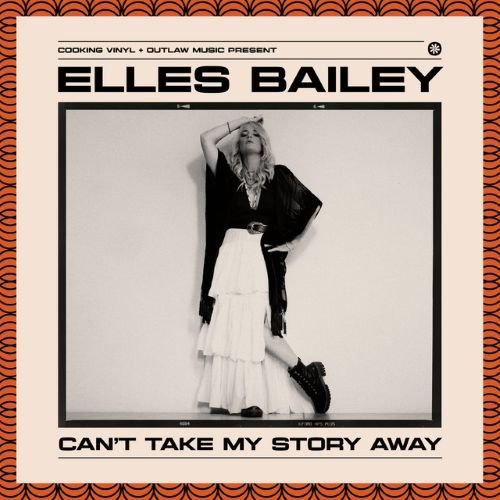

FEATURE:

A Queen of Fashion

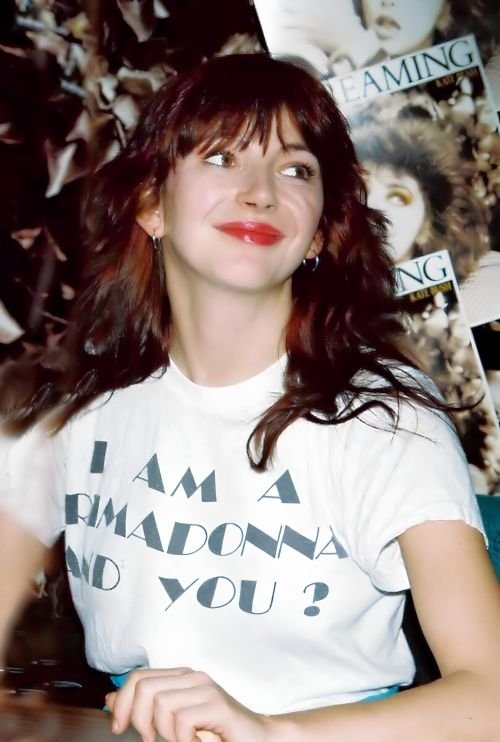

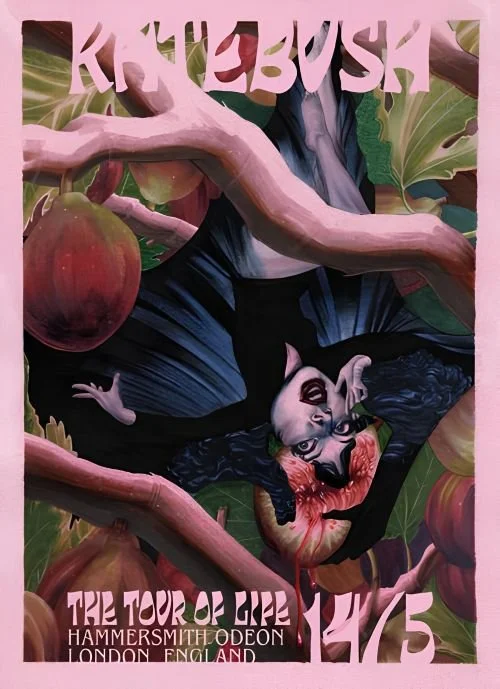

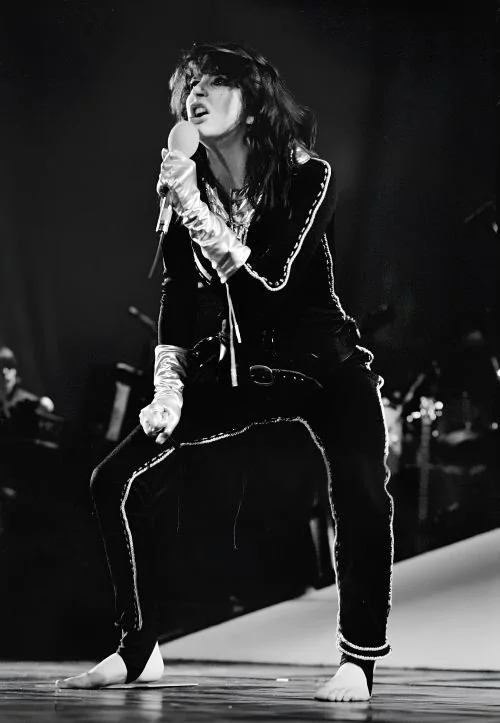

IN THIS PHOTO: The phenomenal Kate Bush photographed 1978/PHOTO CREDIT: Brian Aris

What Are Kate Bush’s Most Iconic Looks?

__________

WHEN speaking with…

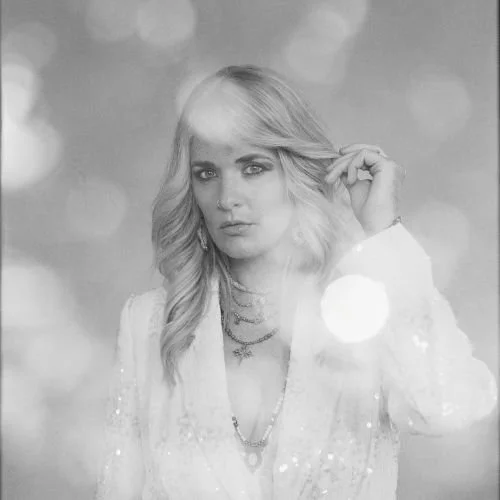

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush in 1989/PHOTO CREDIT: Guido Harari

Ken Bruce in 2005 in promotion of Aerial, Kate Bush said the following: “Clothes are…very interesting things, aren’t they? Because they say such an enormous amount about the person that wears them. They have a little bit of that person all over them, little bits of skin cells and…what you wear says a lot about who you are, and who you think you are…So I think clothes, in themselves are very interesting”. She was referring to the track, Mrs. Bartolozzi. One of the standouts from that double album, I have been considering clothing, style and fashion in relation to Kate Bush. We think of certain musicians and associate them with fashion changes, evolving looks and this iconic sense of style. I guess David Bowie is one. Madonna too. These huge artists who changed their look with every album but retained their core. How often do we associate Kate Bush with her style? I have written about this before. Kate Bush’s incredible looks, in a clothing sense, are more arresting than any other artist I think. I would argue Bush is the most chameleon-like artist we have ever seen. Even in 1978, she was pretty broad when it came to fashion. Many associate that year with leotards, white dresses and basic looks. Cliches about Kate Bush. However, if you look at photoshoots and photos from that year, you do get something broad. However, I feel the biggest changes and shifts came in around 1980 or 1982. When she released Never for Ever (1980) and The Dreaming (1982). Perhaps, as she was producing her own albums by this point, she wanted to have more say about what she wore. Though I always feel that Bush was in control of that. The photo I have included at the top is from 1978. I have included shots from Brian Aris and his collaboration with Kate Bush that year. When many associated her with a particular sound and look that year, she was appearing in shoots looking super-cool in leather. Not someone who wanted to be defined or pigeon-holed. In the same way Bush’s music was broad and she allowed herself this full spectrum of sounds and emotions, she was also eclectic in terms of her looks.

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush at a record signing for The Dreaming at Virgin Megastore on Oxford Street, London on 14th September, 1982/PHOTO CREDIT: Getty Images

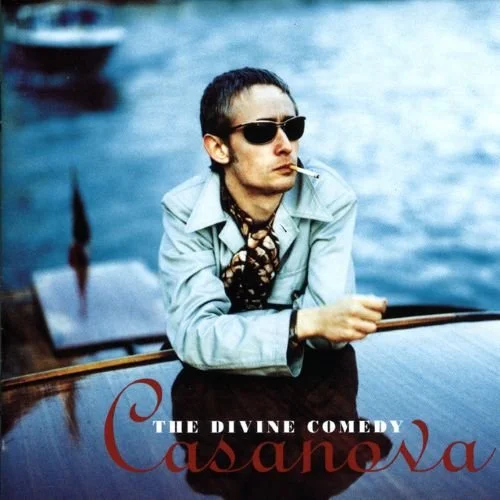

I feel a lot of photographers might have exploited her beauty and sex appeal early on. Bush never wanted her looks to distract or define her. What is evident from her photoshoots is how she was never ordinary or, God forbid, boring. I think the stuff she shot with Guido Harari is particularly memorable. The Hounds of Love shots so arresting and beautiful. Since 1978, Bush effortlessly adopted these looks and personas. Or she was naturally being herself. Though her portfolio is perhaps more variegated and diverse than any artist who came before or since. Even for Director’s Cut and 50 Words for Snow in 2011, she was not resting on her laurels or reigning it in. Always so striking and different. Everyone will have their favourite Kate Bush photos. Where she is quirky, bold or unexpected. Throwing together this look that catches the eye and stays in the memory. I have said how there should be exhibitions where we see a range of photos and outfits. If any outfits remain. I do feel that Kate Bush’s fashion sense and how she could inhabit so many different looks is as striking as her music. Do people have their favourite Kate Bush look? In terms of time period, do you tend to favour those earlier years when she was shooting with Brian Aris and Gered Mankowitz? From leather and lace through to the Claude Vanheye capturing her wearing these extraordinary outfits from Chinese-Dutch fashion designer, Fong-Leng. Maybe shots from Clive Arrowsmith and Anton Corbijn around 1981 and 1982. I think about her album signings when she was dressed casually and was not there for the cameras. However, she was always so cool and distinct. The iconic I Am a Primadonna And You? T-shirt when she was singing The Dreaming. Award shows where she was dressed so fabulously. Even more recent occasions. The outfits for 2014’s Before the Dawn.

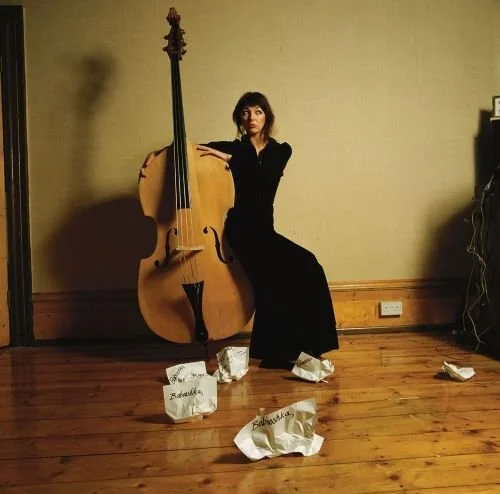

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush in 1978 (though some sources say in 1979)/PHOTO CREDIT: Claude Vanheye

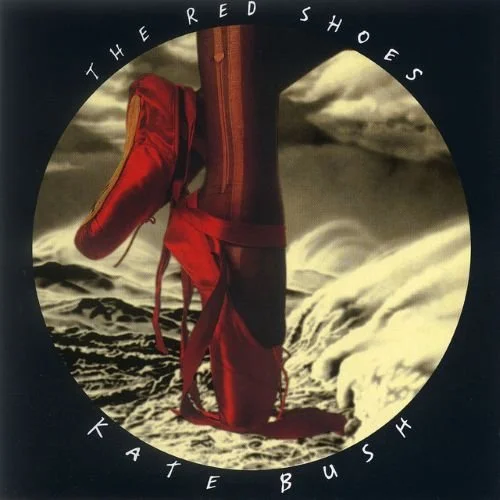

It is staggering considering how hugely broad her wardrobe is! I personally really love the photos she took in 1989 for The Sensual World. And also 1993 for The Red Shoes. Even if many fans instantly go for 1985 and Hounds of Love, you can also see merit in saying 2005 was a peak year. Great shots from Trevor Leighton where Kate Bush looked so incredible. Or those fabulous Gered Mankowitz shots in 1978 and 1979. Capturing Bush more as a dancer than artist. Though his Hollywood shot is perhaps one of the all-time best Kate Bush photos! Bush is undoubtably a style queen. This almost untouched artist who stood out even when she was at her most casual. Perhaps it is just her having this ability to look fabulous and unique in everything! Many write Kate Bush off as being eccentric and odd. Thinking that she just dressed to be peculiar. But you can draw a link between her and Björk. It is about these artists expressing themselves and experimenting. Not wanting to be a traditional artist or being ordinary. It seems hard to narrow down on the most memorable Kate Bush look or shot. I had even forgotten about the Hounds of Love premiere which she attended with Del Palmer and looked stunning in this purple jacket with a white blouse/shirt underneath. In the photos, her hair almost has this red tinge to it. What about the music videos? Babooshka completely different to, say, The Sensual World. Bush looking utterly beguiling (in different ways) in each. I am clearly no fashion or style expert. Maybe it is also her hair and how she wore that. The complete ensemble. The looks Bush could project and how she engaged with the photographer. One of the reasons why I wanted to ask people what their favourite Kate Bush shot or look was is because I follow accounts on Twitter where people share Kate Bush photos. So many that I have never seen. It always stuns me how many different guises and styles Bush had and could effortlessly wow in.

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush shot at the British Rock and Pop Awards, February 1980/PHOTO CREDIT: Mirrorpix/Getty Images

Again, is there an artist who is more iconic in terms of their fashion? Perhaps Kate Bush today is a little more reserved or simply does not need to be anyone else or come up with different looks. However, if there is a new album, will she feature in promotional outfits? It is tantalising that we might see this new shoot where Bush stuns and captivates. I recently ran a feature where I said my favourite album cover is 1989’s The Sensual World. That shot, where Bush has a flower covering her mouth and it is shot in black-and-white (technically a purplish-brownish-black ‘duo-tone’), is staggering and timeless! In terms of the best photoshoots, Guido Harari’s shots for The Sensual World and the looks there are amazing. John Carder Bush (her brother) from the Babooshka single cover shoot. Or the Hounds of Love shots for The Ninth Wave. We can see more of his prime shots here. I love the one for Director’s Cut where Bush is holding a cat. Bush beaming in 1989 with that colourful backdrop. I have pitched before how photographers Gered Mankowitz, Guido Harari and John Carder Bush should get together for a documentary to pour over photos they took of Kate Bush. Discuss the experiences and the looks. There is something about Kate Bush and her fashion that gets into the heart and stays in the mind. How she projects so much of her own personality but also steps outside of that too. Almost impossible to define! Whether effortless cool and casual or appearing in these more high-concept shoots, she never looks out of place. David Bowie, Prince, Lady Gaga, Madonna and Rihanna often cited as the most fashionable and trendy artists. In terms of her breadth and impact, I feel Kate Bush is more iconic and stronger than them all. When it comes to he style and looks, there are no artists who…

IN THIS PHOTO: John Carder Bush captures his sister for 2011’s Director’s Cut

CAN touch her.