FEATURE:

Revisiting…

Iraina Mancini – Undo the Blue

_________

PEOPLE know how much I love…

Iraina Mancini’s music! A hugely talented D.J., artist and songwriter, she released her much-anticipated debut album, Undo the Blue, on 18th August. One of the last year’s best albums, I crowned it my favourite of 2023. Mancini, too, was my artist of 2023. Such an amazing and natural talent, I was lucky to get Undo the Blue and hear it early. I was impressed by many things: the breadth and eclectic nature of the sounds and styles Mancini covered; the incredible songwriting and her wide and stunning vocal range. She brought you into every song and truly captured the imagination and heart with every single note! I wondered about some of the love songs and who inspired them. Which vinyl albums in her collection influenced particular numbers. A flawless album that could naturally translate to a short film/visual project from Mancini, I think that Undo the Blue hints at a very long and prosperous music career. As we wait for the second album – new music is planned but, as it is early days, no release date yet for a second album -, enjoy a golden album full of musical bounty and sonic pleasure. Go and get this truly magnificent album:

“Needle Mythology, the label founded by music writer, author and broadcaster Pete Paphides, release the eagerly anticipated debut album by London singer-songwriter and renowned DJ Iraina Mancini. Iraina’s singular pop vision will be known to regular listeners of 6 Music, where her singles ‘Undo The Blue’, ‘Deep End’, ‘Shotgun’ and ‘Do It (You Stole The Rhythm)’ have all been enthusiastically embraced. Iraina's obsession with music stretches back into her early childhood, much of which was spent absorbing her parents’ collection of old 45s, in particular her dad’s Northern Soul records – an alternative education which meant that, by her early 20s, she was a familiar presence in the DJ booth at many discerning London club nights. Her love of French ye-ye, British freakbeat, Brazilian bossa nova, soul, and Turkish psych will be well-known to regular listeners of her Soho Radio show. Having always sung from a young age, Iraina embarked on a string of collaborators such as Jagz Kooner (Sabres Of Paradise), Sunglasses For Jaws (Miles Kane) and Simon Dine (Paul Weller, Noonday Underground) which truly saw her find her metier as a songwriter, conjuring melodies that stand shoulder to shoulder alongside her impeccable influences. Iraina describes her first single for Needle Mythology ‘Cannonball’ as “a celebration of that moment when you meet someone you really fall for and it knocks you for six. It can be a bit scary, but you’ve just got to go with what your intuition is telling you.” Written with Simon Dine, the vertiginous heart-in-mouth abandon of the song perfectly mirrors the circumstances that brought it into being. Iraina cites Jacqueline Taïeb’s 1967 single 7h du Matin as an early inspiration for the song: “There’s such a great energy about that song. Her vocal is amazing and all those stops and starts that grab your attention.” “This is an artist I absolutely love, one of our rising stars at 6Music.“ Lauren Laverne BBC 6Music”.

I will come to some positive reviews for Undo the Blue. Even though stations like BBC Radio 6 Music gave the singles a lot of love, I think that more publications and websites should have reviewed and spotlighted Undo the Blue. I want to start out with some testimony from Needle Mythology. Run by broadcaster, D.J. and author Pete Paphides, he was thrilled to announce a mighty debut from the tremendous London-based Iraina Mancini:

“Please give a warm welcome to Needle Mythology’s latest signing.

Can I tell you about the first proper conversation I had with Iraina Mancini? We’d met three or four times in passing, at Soho Radio, where we both host radio shows. And by the most recent of those occasions, I’d heard her own music, three self-released singles.It says a lot about the quality of those songs and about Iraina’s sheer determination that she managed to get them playlisted on 6 Music *without a plugger*. That’s almost unheard of. But if you listen to Deep End, Undo The Blue and Shotgun, you’ll know why. These are songs that stick to you on first listen the way they did when you were a kid and you couldn’t rest until you’d either taped it off the radio or got the money together to get them from your local record shop.

So, last November, on the most recent of those in-passing conversations, I asked Iraina if there was an album on the way. She told me that half of it had been recorded, and the other half existed in demo form. “Who’s putting it out?” I asked her. That process was ongoing right now; a bit of back-and-forth with a couple of major labels. They were dragging their heels. I sensed a sliver of opportunity.

“I run a small label,” I said. “Would you mind sending me the songs?”

“Sure!” she nodded. That night, ten songs landed in my inbox. Ten individually beautiful songs; but also, thirteen songs which, all together, propelled you into the fully-furnished, flawlessly-curated pop universe of their creator. Every detail just-so.

Iraina and I met a few days later at Maison Bertaux. I told her about the label. I told her that my job, as I saw it, was to just get out of the way and let her finish what she’d started. She told me about her – for want of a better word – method. About the melodies that come to her as far back as she could remember. Fully fully-formed tunes that flow into choruses that pitch up in your brain, kick off their boots and make themselves at home. A lifetime spent obsessing upon pop in all its myriad forms: northern soul; French ye-ye; bubblegum; freakbeat. From the Supremes to Betty Boo – her interior world was like a radio station to which no-one else had access.

When she talked to me about Deep End, she hymned “the scuzzy sound of 60s garage rock”; the atmosphere of early Jacques Dutronc records, and the adrenalised harmonies of The Shangri-Las. For Undo The Blue (the song), she talked about creating something that might make people feel something of what she felt the first time she heard the luxuriant psych-soul of Rotary Connection.

We also talked about Jacqueline Taïeb, Margo Guryan and Astrud Gilberto. When Iraina stepped up to the mic to sing Sugar High, she asked herself, “How does it make you feel when Julie London and Dusty Springfield sing about love?” If you want to know what the answer is, listen to Sugar High.

During the course of that conversation, I sent myself a dozen texts – reminders of records she’d mentioned that had in some way established the sonic mood board of Undo The Blue. I had a lot of homework to do. But when I heard them all, no single album managed to resound with quite the iridescent joie de vivre that pours forth from these songs. That’s 100% Iraina.

When pop is done with this sort of full-pelt brio and impeccable taste, what you end up with is an album that will repeatedly remind you why you fell in love with this supposedly ephemeral art form in the first place.

And that’s why everyone who has worked with Iraina on Undo The Blue – Will Harris , Mark Wood , Craig Caukill, Julian Stockton, Martin Kelly, Rupert Orton, James Gosling, Erol Alkan, Mig and everyone at Cool Badge – is thrilled to have been part of this adventure.

I had a few ambitions when we started this label, but one of the big ones was to put out at least one genius Platonic-ideal-of-pop album. The sort of record just as good on a sunny Saturday morning when you’re doing the dishes as it does when you’re getting ready to go on a night out with your friends. This is all of that and so much more”.

An artist impossibly cool and wonderful – I am predicting she will play Glastonbury and many other big festivals this year -, I feel she is worthy of a big interview with the likes of The Guardian, Rolling Stone, or even U.S. publications like The New Yorker. I feel that her music could translate to the U.S. easily. Maybe there is not a big budget to tour international, though I can imagine Mancini rocking Los Angeles and New York audiences. Paris seems like a natural haven and home for her music. She toured through the U.K. last year, yet I can feel American attention coming her way soon. In addition to her amazing Soho Radio show, Mancini also does D.J. work at a variety of events and locations. She is someone I can also see having an acting career and being on the small screen soon. Last year, House Collective spoke with Iraina Mancini about her route into music:

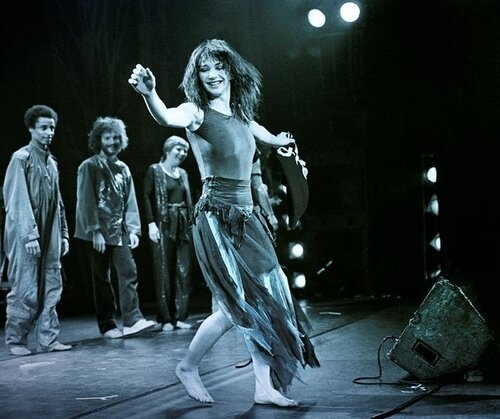

“The sublime retro chanteuse Iraina Mancini is a singer-songwriter whose star has been in the ascendent since the mid-pandemic release of her first single “Shotgun” - a delectable slice of francophile summer-of-love-inspired pop that has been championed by the likes of Jo Wiley and Lauren Laverne, becoming a firm favourite on the BBC Radio 6 playlist. Effortlessly channelling the style of the yé-yé’ girls of the 60s, it's fair to say that Mancini has a somewhat encyclopaedic knowledge of every element of her craft, having DJ’d rare northern soul and funk sets at festivals all over the world as one-half of the disc-spinning Smoking Guns, and via hosting her own weekly radio show on Soho Radio. And she is a musician with strong pedigree, being the daughter of the singer, dancer and composer Warren Peace, who worked extensively with the legendary David Bowie throughout the 70s, among many others. Culture Collective caught up with the soul songstress to talk about the new single from her forthcoming debut album "Undo The Blue", and to get the lowdown on manifesting your dreams as reality.

What set you out on the path to be a musician?

I grew up in a very creative household, my mother was a photographer and my father was a music producer, so I was surrounded by the importance of expressing yourself through art as a kid, whether it was watching my mum develop film in dark rooms or sitting in on music sessions at my dad’s studio. My dad used to sing with David Bowie back in the day, from Aladdin Sane through to Station to Station, so I used to listen to old tapes and watch videos of him on stage – all of that had a huge impact on my life. My love of singing started at a super young age – I used to do vocals for dad in the studio when he had an advert or film to write for, so, even at the age of four, I was singing on a song he wrote for an Italian clothing brand, hilarious! I also had a music teacher at school that really believed in me. I used to write songs, and he used to push me to sing them in church in front of the whole school. When people started to ask for copies of the songs afterwards, I knew that perhaps I was okay!

Why is musical expression important to you?

If I have gone though a bad patch, I tend to need a way to vent those feelings, and emotion and tension can be expressed so beautifully through melodies and harmonies. I have always had a crazy love affair with music, though. There have been times when I have had long breaks from writing, then, all of a sudden I will get a creative burst and won’t be able to stop. It was actually during the pandemic when my music seemed to take off the most, which was interesting. I really had time to focus on it. I released my first single ‘Shotgun’, and that did really well – it got picked up by lot of radio stations and was playlisted on BBC Radio 6, so that was kind of when I thought, oh, okay, hold on, this is kind of working. Then I really buckled down, and, as with all things in life, when you really focus on something, it kind of works out.

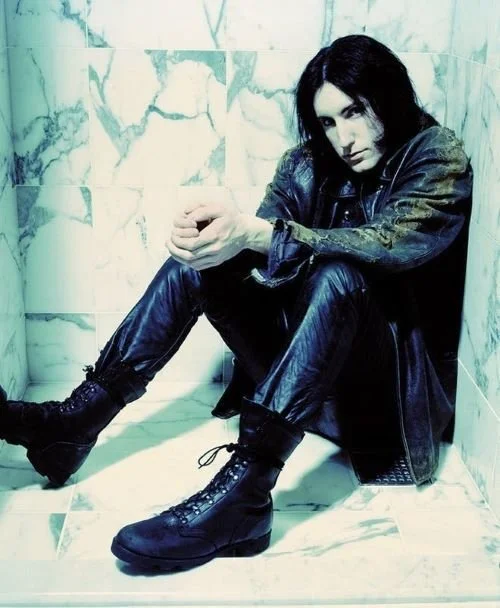

PHOTO CREDIT: Kirk Truman

How would you describe your music?

I would describe it as psychedelic pop. I am very inspired by the 60s and French singers, I love the style of that era. I discovered the album Melody Nelson by Serge Gainsbourg in my 20s and I just fell absolutely in love. I love all the music Serge made. I love the grooves. I love all the girls who he picked to be on the records. I mean, probably chosen because he liked pretty women as well, right? But I don't know – that's one of those things, isn't it? (Laughs) I mean, he was obviously a bit of a player, let's say, but I'm not particularly interested in that side of him, more just the music he made. I think he was a bit of a genius. Nowadays, of course, it's as much about the personality and the way that they choose to live, as well as their art, which can cause problems. I think pre-social media you could actually have some mystique.

What are the key themes on the album?

A lot of it's about a fresh start and letting go of stuff. I had a big relationship end, and I went through a period of self-reflection, and started kind of questioning what was going on inside? I kind of started again, and built myself up again – I did so much work on myself. I really felt like a brand new person afterwards. So, a lot of my songs like “Undo The Blue”, which, which is my latest single, is all about that thing of starting again and undoing the negative. I do find it it's really odd when I write, though. It's like kind of a button I push and it just all comes out – sometimes I don’t know what I'm going to write about at all, I'll just write, and then I'll read the page and it kind of tells me what I'm feeling, and I'll go, oh yeah, that is what's going on in my head”.

Undo the Blue, in my view, is a modern classic. It does nod heavily to classic and older sounds, though it sounds so modern and fresh because of the production and songwriting. It was a shame that this year-best album was not featured by bigger publications. As a result, some people have not heard Undo the Blue. The Afterword were among those to recognised the sublime brilliance and majesty of a phenomenal debut album:

“The first song Deep End has an incredible brass intro and becomes a driving, breathless opener in the style of Republica’s Ready To Go. It certainly got me interested. Iraina gives us a 90s vocal masterclass. Intense and dramatic. OK, I’m in.

Cannonball is more of the same putting me in mind of Garbage this time. I suspected this was where Iraina’s influence lies before I found out more about her. It’s an era that almost passed this 80s boy by but this song has that voice, guitars, organ, passion and plenty of hooks to drag me along.

Sugar High is a lovely shift in styles. Jazzy and dreamy. Iraina’s voice sounds amazing and my crazy brain is getting Olivia Newton John pre-Grease during the chorus. Imagine Olivia doing a Style Council or Blow Monkeys song and we’re there. The string arrangement is exquisite. This is absolutely lovely.

The title track is another smooth delicious piece of pop. I’m going back to Dusty now or Lenny Kravitz doing It Ain’t Over. In fact, such is the range displayed here there it goes from those unlikely sisters Swing Out and Shakespears. It has a fabulous crescendo moment, harmonies and swoon. Some song this.

Do It (You Stole The Rhythm) and we’re back in the 90s with a baggy rhythmed slightly underwhelming song only elevated by Iraina’s voice. Maybe it’s a grower, a slow burner lost in an inferno.

My Umbrella has more than enough hooks for any one song. It’s the Astrud Gilberto moment. Even my old hips are moving (in their own time but moving none the less). I need a hot day, a fast car and an open road to seal the deal on this song. Ooh it’s very good.

Shotgun could be the theme to a smart 60s / 70s detective thriller. It’s no Shaft but it has that smokey late, hot New York night vibe. If Netflix don’t start developing Shotgun on the back of this then they’re not really trying. If Regé-Jean Page doesn’t get Bond somebody send him this song.

What You Doin’? Annoys me in a good way. I’m failing because there’s a 70s glam song in there that wants its groove back and I can’t bloody get what song it is. Suzi Quatro maybe? Showaddwaddy? Can someone help? I am also afraid that What You Doin’? the monster earworrm it is will be rattling round my head at 2 am denying me sleep. Especially if I can’t find what it reminds me of.

Need Your Love is, surprise surprise, a love song with a feel of a Bond theme. A great showcase for Iraina’s vocal range but doesn’t really get going until a lovely spoken section. I will grow to love it I’m sure. Just needs more listens.

In a flash we are at the last song Take A Bow. Come on Iraina let’s finish on a high. She goes back to the 60s again. Join her and float on a gorgeous ride through the great chanteuse of our time. Pick out the voice of your choice it’s in there somewhere. Take A Bow Indeed.

What does it all *mean*?

I’d seen so much about this album on Twitter that it had become like white noise. I came to it with quite a bit of negativity. Come on then, prove you’ve worth all the fuss. I should have trusted Pete. This is something very special that I wouldn’t have listened to without the relentless plugging. Maybe this is the album that will prove to me that despite me being so entrenched musically there is other stuff out there for me. New stuff. You know that special place you always wanted to go but just couldn’t bring yourself to Dave? It’s right here now go and find some more. Cheers Pete. And Iraina obviously.

Goes well with…

Anything really. It’s the sort of album you could put on anywhere and it will lift yours and the mood of anyone listening. Dare I mention Sade here?”.

Undo the Blue was my favourite album of last year for a reason: every song is unique and has you completely gripped. Pete Paphides said Undo the Blue is an album with only singles on it. All the classic albums feel like every song could do well in the charts. That is the case with Undo the Blue. I am not sure whether Iraina Mancini is tempted to release one more single from the album – I know many would love to see a video for the stunning album closer, Take a Bow -, though I guess moving on and creating the blueprints for the second album are in her mind. Seriously, if you have not heard the wonderous and unforgettable Undo the Blue, then go get the vinyl, drop the needle and let it…

TAKE you somewhere blissful!