FEATURE:

Family Business

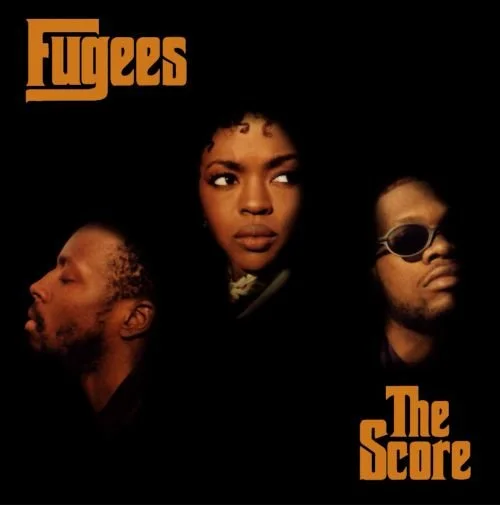

Fugees’ The Score at Thirty

__________

ONE of the most important…

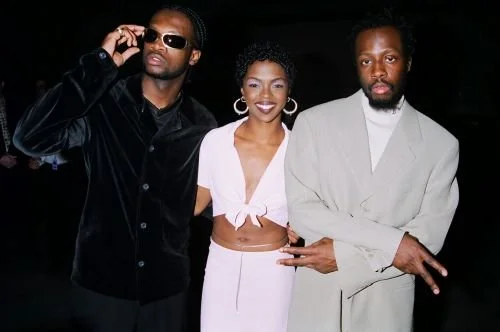

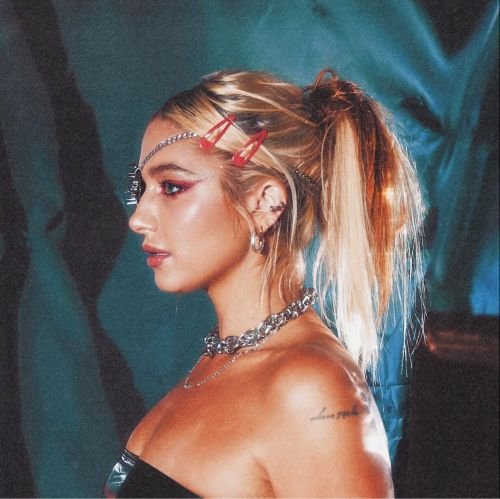

IN THIS PHOTO: Pras, Lauryn Hill and Wyclef Jean of Fugees/PHOTO CREDIT: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic

and extraordinary albums of the 1990s turns thirty soon. The masterpiece second studio album from Fugees, the trio consisted of Ms. Lauryn Hill, Pras (Michel) and Wyclef Jean. I shall finish with a review for The Score. It is one of the biggest creative leaps ever. 1994’s Blunted on Reality is an okay album, but it only has moments of brilliance. The Score was a huge step forward. I think because it featured more of Ms. Lauryn Hill. Her voice seemed to be more prevalent. She would release one solo album, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, in 1998. Released on 13th February, 1996, The Score reached number one in the U.S. Production was handled by the Fugees, Jerry Duplessis, and Warren Riker. In terms of he tracks on the album, it features Ready or Not, Zealots, Killing Me Softly with His Song, and Fu-Gee-La. It also has incredible deeper cuts such as How Many Mics and Family Business. Fugees have performed together since The Score was released, though there has been nothing in terms of huge gigs or anything significant. I feel there are splits and tensions within the group. At the end of last year, Pras (Pras Michel) was sentence to fourteen years in prison for using money to peddle political influence in the U.S. It means that the trio will not reform or play any gigs together. It sort of gives The Score a more complex legacy than it would otherwise have had. Not that members of Fugees have been free from controversy through their careers. However, with the sentencing of Pras Michel, it does mean that any hopes of a fully-fledged tour or reform is now impossible. Certified seven-times platinum in the U.S. and one of the most popular and influential albums in Hip-Hop history, I do hope there is retrospective about The Score around its thirtieth anniversary. Controversy and splits within the group do not take away from the brilliance and importance of The Score.

In 2021, SPIN shared an article that they first published in April 1996. An interesting interview with Fugees, it must have been exciting seeing the trio release this amazing new album after what could only be described as a somewhat middling debut. The Score was the album they had been promising. Their second studio album would prove to be their last:

“In hip-hop’s cosmology, “hardcore” rap means a cantankerous MC kicking rhymes like bodies over harsh, skeletal beats. “Alternative,” on the other hand—singing, melodies, instrumentation, any sort of peace-and-love attitude—translates as “no skills.” So hip-hop trio the Fugees—Wyclef “Clef” Jean, Lauryn “L” Hill, and Prakazrel “Pras” Michel—aren’t at all pleased to be in this section.

“We are a hip-hop group, point blank,” says 20-year-old Hill, a doe-eyed gamine of startling beauty and as brawny and nimble a rapper as she is a rapturous soul singer. “‘Alternative’ is like saying ‘she’s attractive for a dark-skinned girl,’ a backhanded compliment. Just because we can play instruments, we can’t be real hip-hop? The reason I make the kind of music I make is to bring musicality back to the ghetto. It’s about being creative, and sometimes adding a motherfucker if it means getting my point across.”

The Fugees titled their sophomore effort The Score because it settles that issue the best way possible, with moody spaghetti-Western riffs, noodling jazz horns, R&B memories, Jamaican rude-boyisms, a radical reinvention of Roberta Flack’s “Killing Me Softly With His Song,” and the Refugee Camp’s own live instrumentation. The Score leads off with “Red Intro,” a street-corner poetry rant from Ras Baraka, son of poet Amiri Baraka. A flowing edit takes us to the Fugees, smoked out and ripping lyrics back and forth to sound an old-school battle cry. “I used to be underrated / Now I take iron / Makes my shit constipated / I’m more concentrated,” raps Hill.

“That gangsta shit is B.S.,” says Jean, the group’s live wire guitar hero and at 26 the oldest. “The real thugs and gangsters got the rappers saying that shit. The gangster to me is the guy who owns Sony [the Fugees’ label], the guy who owns SPIN, the guy who owns MTV. Hardcore is like being in the house with the eight of us, mom on welfare. That’s what I call hardcore. I don’t mean to sound preachy ’cause we’re a bug-out group.” “Hardcore for hard times,” says Hill more succinctly.

The trio met eight years ago at Columbia High School in South Orange, New Jersey, when Hill entered her freshman year. Haitian-American Michel, a junior and the son of a church deacon, asked her to sing on his rap tracks. They were joined by his older cousin Jean, a self-taught musical prodigy, himself the son of a fire-and-brimstone preacher who hated Jean’s “devil’s music” and once refused to sign a label contract his then-underage son was offered. In a gesture of proud defiance, they named themselves the Fugees for the Haitian refugees who were then washing up on U.S. shores.

Except for Salaam Remi’s straight-up hip-hop remix of “Nappy Heads,” the Fugees’ 1993 Blunted on Reality debut pleased music critics and confused radio programmers and hip-hop purists. No wonder: Jean cites as influences an eclectic mix ranging from Eek-a-Mouse and Peter Tosh to B.B. King, Thelonious Monk, and even the Pet Shop Boys and Yes. The classic-R&B-loving Hill, who worked as a teen cabaret singer and theater actress, today studies history at Columbia University. “In class, I’m always like ‘hey, does anyone else notice that this is the same shit that made it so conquest and subjugation was the basis upon which America and the West was built?’ You know what I’m saying? It’s always Machiavelli, Hobbes, Locke.”

As the album flopped, Hill’s featured appearance in Sister Act II inspired suggestions that she take up the mic solo. “I don’t find it a compliment when people say that,” Hill says heatedly. “These brothers are like members of my family. Families sing together and they blend. There’s something that we do together that makes perfect chemistry. It’s been perfect since I was 14 years old.” Jean raps his response in The Score‘s “Zealots”: “The magazine says the girl shoulda went solo / The guys should stop rapping vanish like Menudo / Took it to the heart / But every actor plays his part. / As long as someone was listenin’ / I knew it was a start.”

This time around, the Fugees produced the album themselves, creating the same impromptu spirit in their New Jersey Booga Basement Studio that they have in their dynamic live act, a revamp of an old-time soul revue that’s one of the best shows in hip-hop. Steering clear of “A” audiences, they’ve been playing to the hip-hop heads in the hoods, the “hardcore audiences, blunt smokers, weed smokers, gun toters, like kids on our block who we grew up with,” says Jean. “I can hold my guitar or sing, but it’s with a rebel voice.”

Their efforts seem to be paying off. In late December 1995, the Fugees won “The Battle of the Beats” on Hot 97 (a New York City hip-hop radio station) five nights in a row with The Score‘s “How Many Mics,” defeating the Wu-Tang Clan and “whatever is so-called hip-hop today,” says bass-voiced Michel, a tall, lanky 23-year-old not easily impressed. “Hip-hop is a culture—dance, lingo, style, music—and that’s what the Fugees is. Anyone can rap”.

In 2021, Consequence wrote a feature celebrating twenty-five years of Fugees’ The Score. For anyone who wants to understand the rawness of '90s Hip-Hop, they recommend that people listen to this album. One, they say, that remains an oracle twenty-five years after its release. A further five years later, and whilst its legacy might have changed or been affected by circumstances within the group and around its members, the power of the music remains undiminished. Maybe as powerful now as it was in 1996:

“Part of its lasting impact stems from the trio of Wyclef Jean, Lauryn Hill, and Pras Michel having released their classic sophomore effort in a year where the fabric of Black music was palpably changing. In 1996, the world would witness 2Pac’s last release (All Eyez on Me), the beginning of Jay-Z’s musical reign (Reasonable Doubt), and debut albums from game-changers Lil’ Kim (Hard Core) and Foxy Brown (Ill Na Na). Influential groups like Outkast and A Tribe Called Quest also released notable projects that year (ATLiens and Beats, Rhymes and Life, respectively), but the presence of women emcees in rap groups was practically nonexistent. Blunted on Reality, the Fugees’ vastly underrated debut record, had first introduced hip-hop audiences to Ms. Lauryn Hill and her New Jersey outfit back in 1994, but it would take the group’s groundbreaking follow-up a couple years later for them to gain widespread notice.

That punched ticket was 1996’s The Score, which rightfully cemented Fugees’ place in hip-hop history and boasts the hardware to prove it. The album was certified six times platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America. At the 39th Annual Grammy Awards, The Score won for Best Rap Album. The sonic eclecticism that set the group apart from their contemporaries stemmed from their Haitian roots. “Everybody seeks refuge,” Jean told Vibe magazine in 1996. “We find refuge in music.” The way the album infused Caribbean melodies and sounds with soul, reggae, pop, and R&B — in addition to their use of timeless samples and potent lyricism — made it an instant classic.

“Red Intro”, featuring an appearance from Ras Baraka (son of poet Amiri Baraka), acts as a gritty and dramatic harbinger for The Score’s esoteric and gripping themes regarding capitalism, identity, and the normalization of hyperviolent masculinity. The spoken-word dimensionality of “How Many Mics” reveals that Hill, who rips through the introductory verse with equal parts passion and skill, plays second fiddle to absolutely no one: “Laced with malice/ Hands get calloused/ From gripping microphones from here to Dallas/ Go ask Alice if you don’t believe me/ I get in her visions like Stevie /See me ascend from the chalice like the weed be.”

She continues to ride her own wave on the explosive “Ready or Not”, which boldly samples Enya’s “Boadicea”. Hill proves her mellifluous prowess as a vocalist and rapper and venomously declares: “So while you imitating Al Capone/ I’ll be Nina Simone/ And defecating on your microphone.” Jean’s precocious wordplay coupled with Michel’s knavish similes (“I refugee from Guantanamo Bay/ Dance around the border like I’m Cassius Clay”) showcases the chemistry that makes the Fugees such a formidable trio on The Score. Jean was the provocative mouthpiece that teetered between revolution and redemption; Michel was the stern, yet playful, poet who would often get enthralled with his own musings; and Hill was the unpredictable virtuoso that bonded them together so remarkably well.

“Zealots” playfully and boldly pays homage to the ’60s doo-wop era. “The Beast” treads into political territory with razor-sharp precision by bashing Republican figures like Newt Gingrich by name, calling out the disturbing regularity of police brutality and America’s racist prison problem. Jean’s poignant observation of how wealth won’t save him from discrimination since he’s still a Black man is piercing: “My inner conscience says throw your handkerchief and surrender/ But to who? The “Star-Spangled Banner”?/ Oh, say can’t you see cops more crooked than we/ By the dawn early night, robbin’ niggas for keys/ Easy, low-key crooked military/ Pay taxes up my ass/ But they still harass me.”

Hill effortlessly floats on its follow-up, “Fu-Gee-La”, as she interpolates Teena Marie’s 1988 hit “Ooh La La La (If Loving You Is Wrong)” for the chorus while adding a bit of her own pomposity: “Ooh, la-la-la/ It’s the way that we rock when we’re doing our thing/ Ooh, la-la-la/ It’s the natural la that the Refugees bring.” As the lead single from The Score, “Fu-Gee-La” epitomizes how the three artists aptly complement each other: Hill’s vocal lucidity is a perfect contrast to the ebb and flow of Jean and Michel’s forward-thinking verses.

However, the album’s signature moment remains when Hill takes center stage on the Fugees’ rendition of the 1973 Roberta Flack classic “Killing Me Softly”. It feels bare and extremely intimate even as the bass drops 90 seconds into the song. Jean’s adlibs (“One time! Two times”) add a little gusto on a record that is already perfect. In the UK, this famed cover was the biggest-selling single of 1996. It was massive in the States as well and hit No. 2 on the Hot 100. It also won Best R&B performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal at the 39th Grammy Awards ceremony. “Killing Me Softly” celebrated Hill’s powerhouse range, which remains entirely immersive whenever it is showcased.

From beginning to end, The Score is a cogent representation of the arduous, yet resplendent, nature of hip-hop. All of its complexities — which encompass poverty, sexism, institutional racism, and inter and intraracial violence — are harrowing to hear but necessary to know and understand. Fugees acted as truth oracles whose inventiveness went on to inspire generations of rappers to come. The Score has stood the test of time and is a necessary listen for those looking to understand the rawness of ’90s hip-hop. Reflecting on its impact 25 years later confirms something that the group knew when they started making music together: The Fugees were always ahead of their time”.

I am going to end with a Pitchfork review of The Score. However, in 2016, they marked twenty years of a Hip-Hop classic. They also spoke with those who collaborated on and affected the album, including the late great Roberta Flack (who recorded the original version of Killing Me Softly/Killing Me Softly with His Song). It is a fascinating read:

“From the group to the label to the producers to the guest stars, no one had predicted the impact The Score would have on the music world. Once the album landed on the Grammys stage in '97, where it took home two awards, it seemed like the Fugees had it all together. Internally, though, it was another story. The tumultuous romantic relationship between a very young Hill and Clef, who was married and six years her senior, reached its peak during the recording of The Score. L-Boogie would loosely document the affair in her 1998 opus, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, while Wyclef would be more blatant in his 2012 memoir. Specifics remains hazy and have evolved into urban folklore—everyone who touched the project has one story or another. Pras recounted one harrowing tale of Wyclef breaking up with Lauryn moments before she entered the booth to record "Ready or Not," Hill crying her eyes out as she sang the hook. Then there are the stories surrounding The Score's tour, where Hill and Jean briefly reconnected before Lauryn got together with Rohan Marley. And to this day, fans speculate that Hill’s suicidal thoughts on "Manifest" were because of Clef, but who really knows? What we do know is that the love child of this toxic romance became one of the best-selling hip-hop albums ever. Strip the love, the hurt, the bickering—strip it all, and you still have a masterpiece that made history.

Salaam Remi

Producer on "Fu-Gee-La" (The Score’s lead single), "Nappy Heads" remix (from Blunted on Reality), "Vocab," and "Ready or Not" remixes (from Bootleg Versions EP)

"Going into ’95, I was working on music for Spike Lee’s Clockers. I had [the Fugees] come down [where I was working], and we did a song that was supposed to be on The Score but never got on there, called ‘Project Heads.’ During the session for ‘Project Heads,’ which I was also trying to get into Clockers, there was a beat I had made for Fat Joe that Lauryn heard. She was like, ‘Look, where’s that Fat Joe beat?’ During that session, I played the beat on her request and Wyclef jumped up and pretty much spit his verse, ‘We used to be number ten, now we’re permanent one…’ What I did was—on my dime and my time—I recorded ‘Fu-Gee-La’ in my studio. That song was done, and then they went and got the budget for that second album. Then, they started working on beats. First David Sonenberg [Fugees’ manager] wanted me to produce the whole album along with them, but I wasn’t really with it at the time. So I was like, ‘Come to me if you need some advice and I will chime in here and there.’

"Basically, the vibe of The Score was based around ‘Fu-Gee-La.’ If you take away ‘Fu-Gee-La’ it’s there, but ‘Fu-Gee-La’ is The Score, so that’s why it ended up being the first single. With that, Wyclef had his verse, and Lauryn went through singing a lot of different things, from ‘Never Dreamed You’d Leave In Summer’ [which she would later sing on Common’s 'Retrospect For Life'] to Chaka Khan records to all types of stuff. When she finally hit that ‘ooh la la la,’ that was the hook. During that process, Lauryn probably recorded her 16 bars every day for seven days straight. She came back in every day to redo it, because she’s that level of a perfectionist.

"At one point Lauryn hit me and said she was doing a singing record on the album and wanted me to produce it. But at that time they didn’t really have the budget. So Pras calls me one day like, ‘Yo, let me ask you something. If we wanna do "Killing Me Softly," how would you approach that song?’ I was like, ‘Hmmm, I would kind of do it like "Bonita Applebum."’ He said, ‘Oh, that was the same thing I was thinking. I’ll call you right back.’ And there you go: They literally made ‘Bonita Applebum’ into ‘Killing Me Softly.’

"The combination: Wyclef was very eclectic, Lauryn knew every soul song under the sun—she’s like a jukebox—and then Pras. If you look at that album, it says the executive producer is Pras, co-executive producers are Wyclef and Lauryn. It’s because Pras has the pop ear. From my perspective, a lot of their process during The Score was, ‘What would Salaam tell us to do?’ It’s because we had gotten to that point where I mentored them into now taking their talent and molding it into a record that people liked..."

Roberta Flack

Fugees covered "Killing Me Softly With His Song," the most famous version of which—a No. 1 in 1973—was Flack’s.

"Honestly, I had not [heard of the Fugees prior to 'Killing Me Softly']. The Score came on us like a mighty wind, and I was totally blown away by the power of the group—their musicality, their political message, and their creativity. They wanted to change the lyrics [to 'Killing Me Softly'] to make the song about anti-drugs and anti-poverty. They were all about politics. Given their name and all, the (Re)Fugees, it made sense. It was more Norman [Gimbel] and Charlie [Fox] [the songwriters behind 'Killing Me Softly With His Song'] that wanted their song to not be changed. I feel that the meaning of the song changes depending upon the singer, depending upon the listener. They gave the song a new meaning and exposed it to a new generation. They invented a new version of the song, using some musical ideas from my version. I was surprised they picked that song to be included with the others on that album, as it didn’t have the political emphasis, but then again it depends on the frame of reference from which you listen, right?"

In 2021, The Ringer shared a compelling piece that argued how, on The Score, Fugees disguised resistance as art. This huge political statement as any Hip-Hop album of the decade, songs like Fu-Gee-La, are especially important when it comes to representing and putting into focus those displaced. Refuges and those oppressed. The Score gave voice to hose people. In some ways, The Score has a new relevance in the modern-day. In terms of asylum seekers and refugees who are being villainised and risking their lives to find safety. Those murdered by genocidal regimes. There is nothing in modern music like The Score:

“The Score matters because there are places where the blatant political statement, extremely effective as it is, cannot go. When I was 12, I was at a fairly conservative school where a Black friend was ordered to remove his Malcolm X T-shirt by a member of the staff. As my friend retreated to his bedroom to change, the staff member offered her verdict on the civil rights activist. “Horrible man,” she scoffed. However, if she had seen a T-shirt bearing the faces of the Fugees, she might not even have looked twice, even though their underlying message was just as radical as so many of Malcolm X’s speeches. The Fugees disguised resistance as art, the same way that enslaved Africans once hid martial arts from their colonial masters by pretending that they were a dance.

They needed this disguise all the more, particularly because—as historian and professor Tricia Rose has observed—this was an era when major radio stations and media outlets were aggressively promoting hip-hop that celebrated materialism, which generally made it harder for music with the content of The Score to cut through. So much of that period featured feuds that were aggressively stoked by outsiders, especially by media outlets seeking controversy: It is poignant to remember that, even at the height of the supposed Cold War between the East Coast and the West Coast, rappers from both of those areas hung out with each other—Pras, a friend of Tupac’s, was in touch with him shortly before the rapper was murdered. That the Fugees managed to fight their way through that toxic fog, and to show the world that their style of hip-hop was commercially viable—it sold 22 million copies worldwide—is an understated part of their legacy.

At the core of the Fugees’ resistance was their assertion that, contrary to most current and historical narratives, it was cool to be a refugee. The name of their group, chosen to honor the Haitian heritage of Pras and Wyclef, suggested that a refugee was an outlaw, a warrior-spirit; the name of the album, The Score, implied that the act of fleeing one’s country for another was as daring as carrying out a heist at a heavily guarded casino. (If anything, it is much more so.) This reframing of escape as a courageous act rather than a cowardly one spoke to those times, and it speaks to ours now.

When the Fugees released The Score, the West had just witnessed—and, if we are being honest, refused to prevent—two of the most horrifying human rights abuses in recent memory, both of which had led to the mass exodus of people from their homelands. In just a few weeks in 1994, hundreds of thousands of people were slaughtered by their fellow citizens—in many cases, their neighbors—in Rwanda. In 1995, over the course of just 12 days, the same thing happened to 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys in Srebrenica. In the global consciousness, the stock of the refugee was therefore particularly low—people in conflict zones were meant to be killed and not heard. The Score arrived in that world, defiant and unashamed, daring and endlessly epic.

If we fast-forward to the present day, we see that the position of the refugee is similar, perhaps worse. When war came to Syria in 2011, the thousands of people who escaped were largely seen as part of a crisis, their suffering portrayed as a burden for the countries they ran to rather than a tragedy. When those people, along with others fleeing horror of similar intensity in Libya, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, started drowning in huge numbers as they attempted treacherous trips to Europe, the response of much of the European media and politicians was merely to mock them. In the most infamous case, a British tabloid referred to refugees as “cockroaches”—a description which drew a horrified rebuke from the United Nations’ high commissioner for human rights, who compared it to language used by the Nazis.

The Score recast these people, the most disposable of all humans, as mythical figures. “I, refugee from Guantanamo Bay / Dance around the border, like I’m Cassius Clay,” raps Pras on “Ready or Not.” And this album did not portray images of gentle souls, either. These were not the type of refugees who would arrive in a new country and live quietly and fearfully in their buildings, hoping that no one paid them too much attention. In other words, the Fugees were not “good immigrants.” Their work was a blend of heavenly melody and lethal wit. As Hill put it, they were “sweet like licorice, dangerous like syphilis.” Even their heritage was radical, with Wyclef hailing from Haiti—a nation long maligned for its poverty, but which in the early 19th century was the home of the world’s first successful revolt against enslavers”.

I am going to end with a 2021 review from Pitchfork. They awarded The Score 9.3 (and unusually high score for them!). Such a seismic and enduring album, they dissected and passionately discussed “a socially conscious blockbuster grounded by the realities of the immigrant experience”. I heard the album for thew first time at the end of the '90s. It had an impact on me. In years since, its significance has grown. It is one of my favourite albums of the mid-1990s. A masterpiece:

“Upon its release, few would believe that The Score would represent nearly a quarter of Lauryn Hill’s creative output. She had long been identified as the group’s breakout talent, fending off suggestions—and offers—to leave her group behind long before it eventually dissolved. She seemed to have been anointed for stardom from a young age; Before graduating high school she had already acted in an Off-Broadway play (Club XII, the hip-hop Twelfth Night), daytime soap (As the World Turns), and two feature films (Sister Act 2, King of the Hill), as well as releasing the Fugees debut. In the face of the undeniable talent on display on The Score, she grew tired of feeling that people (and press) assumed that her male collaborators were largely responsible for her—and the group’s—success, tired of being seen as Wyclef’s girl.

And while she would evolve into something bigger than hip-hop on her 1998 solo debut The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, her work on The Score remains unparalleled in the genre; no MC has ever sung with such soul, power, and grace, nor has any singer ever spit as hard as she does here. If that statement sounds histrionic, just try to come up with a list of her peers that sing and rap even remotely as well as she did. Cee-Lo? Pharrell? Drake? It’s laughable. There’s a reason why everyone freaked out when Azealia Banks dropped “212”; the skillsets just do not often intersect, despite the AutoTune crooners that have since flooded the pop charts. And even the OGs place her at or near the top of their best-ever MC lists. Yet even after all the praise and recognition, she still felt somewhat unseen, somehow unappreciated. This would manifest itself in Miseducation, both in its powerful expressions of vulnerability and in her tyrannical exclusion of her collaborators from that album’s writing and production credits.

The Fugees recording career barely lasted three years. Flooded with offers and opportunities in the wake of their multi-platinum opus, the group began to fracture. Wyclef began recording The Carnival, supported—both emotionally and creatively—by Pras and Lauryn, who both make guest appearances. But when Lauryn started writing songs for her own solo debut, Wyclef gave her the cold shoulder, a stinging rebuke in the wake of the many solo opportunities Lauryn had spurned in solidarity with her group. The dynamic was made all the more awkward by their clandestine romance, despite his marriage to another woman, and later, Lauryn’s with Bob Marley’s son Rohan. And when the birth of Lauryn’s first child became embroiled in a paternity scandal, the fracture became a fissure, ending hopes of a prompt reconciliation.

The Score was the product of chance alchemy, made by three artists whose independent visions coalesced just long enough to create something remarkable. In the process, they laid out a template for hip-hop’s cleared-sample era, where the curation of old records was more important than how you chopped it up and disguised it. Rappers and producers quickly realized that if you had to pay for it, you might as well make the sample recognizable to those that remember the orginal, and court that new audience in the process. “Killing Me Softly” exists across several decades: It borrows from the Roberta Flack version, which itself a re-arranged cover of the Lori Lieberman original; the Fugees version adds the boom-bap drum beat from A Tribe Called Quest’s “Bonita Applebum,” which itself samples “Memory Band” from Minnie Riperton’s Rotary Connection.

The Fugees managed to diversify the voice of the ghetto, one often depicted in a single dimension. They reclaimed pride for Haitians worldwide, a heritage maligned for its postcolonial poverty and strife but still remembered as the setting for the new world’s first successful revolt of enslaved people against their oppressors. Their sound was multifaceted because they were, too, their music diverse, just like the Black experience”.

Ahead of its thirtieth anniversary on 13th February, there will be new pieces and articles written around Fugees’ The Score. The landmark album has this incredible legacy. That is the main takeaway and thing to remember: the sheer brilliance of the music and the dynamic within the trio. I think Ms. Lauryn Hill’s growing role as a vocalist is what makes it such a powerful masterpiece The Score stronger and more immediate than Blunted on Reality. The confidence in the group and the consistency is higher. After thirty years, few other Hip-Hop albums have such weight and importance. Its relevance is still so huge. Even though Fugees would not last much longer beyond 1996, The Score is an album that shows them…

AT the peak of their powers.