FEATURE:

Blood Roses

Tori Amos's Boys for Pele at Thirty

__________

IT is quite common…

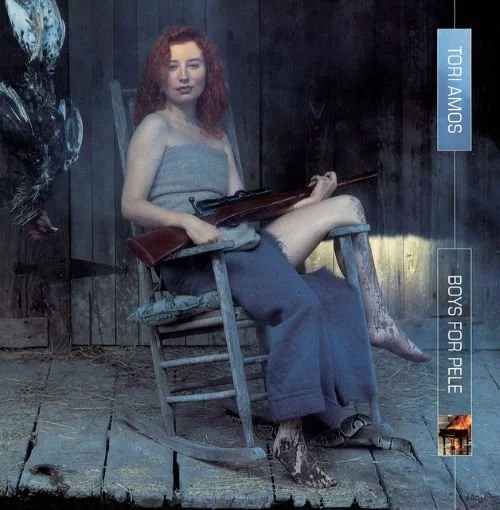

IN THIS PHOTO: Tori Amos in 1996/PHOTO CREDIT: Cindy Palmano

that a third studio album is the moment an artist changes direction and asserts more production autonomy. It happens with a lot of solo artists. I mention it enough when I write about Kate Bush and her third studio album, Never for Ever. Bringing different sounds into her music and co-producing, it was a step forward for her. It has happened with so many artists. I am not sure why the third album particularly is the point in which this happens. It was also the case for Tori Amos. After two successful and hugely acclaimed albums – 1992 Little Earthquakes and 1994’s Under the Pink -, 1996’s Boys for Pele found her recording in rural Ireland and Louisiana. A broader album (of eighteen tracks) that features harpsichord, clavichord, harmonium, gospel choirs, brass bands and full orchestras, she also served as sole producer for her own album. This was a big moment in terms of Amos truly deciding on the direction of her album. Amos had co-produced before, but this was her in the driving seat solo. Even if the songs are seen as less commercial or ‘radio-friendly’, I do feel that Boys for Pele is underrated. Recorded across multiple studios, Boys for Pele reached number two in the U.S. and U.K. It was a massive success for Amos. As it was released on 22nd January, 1996, I wanted to mark thirty years of a truly great album. I am going to come to some features about Boys for Pele, and I will end with a review from Pitchfork. It is fascinating how Tori Amos’s sound, aesthetic and production changed from 1994’s Under the Pink to Boys for Pele. For anyone curious, I would urge people to get the 33 1/3 book about Boys for Pele that was published in 2018. Amy Gentry, the author of the book, published an extra from her book for The Guardian that caught my eye:

“It started with the album art. The cover insert for Little Earthquakes (1992) had been in excellent taste, featuring lots of white space, its bulbous, phallic mushrooms the only hint that something wasn’t quite right; Under the Pink (1994) pictured a miniature Amos, etherised in flowing white and surrounded by crumpled cellophane-like layers of atmospheric transparency. On the cover of Boys for Pele, she was life-sized and filthy, covered in mud and hoisting a gun in front of a dilapidated shack. In other images, her piano was engulfed in flames and appeared to be stranded at a truck stop outside of town, as if it had broken down on the road in the middle of the night. Amos herself seemed trapped in The Waste Land by way of an Erskine Caldwell novel. She suckled a piglet; she posed on all fours in a barnyard, among the animals and garbage, one shoe missing, face turned away from the camera, her once-white clothes now the same soiled colour as the squalid mattress under her knees.

The album sounded like a wasteland, too. A bull groaned in the background of Professional Widow – shades of Tobacco Road again – and other, less identifiable sounds presented themselves throughout the album. On some tracks, the piano was so distorted that it sounded as if it really were being set on fire; and although it still appeared on every track, it had been demoted, replaced as the dominant instrument of the album by the harpsichord, a piano with a head cold and a nasty sneer. Softness was all but missing from Boys for Pele; at once alien and archaic, the harpsichord is not capable of softness. The transitions were too abrupt, the stripped-down songs too stripped-down – Twinkle was a one-finger lullaby, Beauty Queen a single note plunked over and over – and the whole thing sounded as if submerged, not in musical white space, but in something like black space. The more complicated songs, Blood Roses and Professional Widow and In the Springtime of His Voodoo, were exhausting, the thread of their bizarre lyrics and multiple bridges and breakdowns and deliberately contorted vocals impossible to follow. Melodies were stretched like taffy and then suddenly interrupted to make way for abrasive, spitting lyrics: You think I’m a queer, I think you’re a queer! Chickens get a taste of your meat! Stag shit! Starfucker! It better be big, boy! Fragments of prettiness would reenter the scene, skewed and nonsensical, Band-Aids of grace just soft enough to hurt when ripped away.

“Mannered” was not a word I knew to use in high school, but mannered it was. Boys for Pele was Tori Amos’s baroque phase. It was also the last time she ever allowed herself to be quite that ugly, and ugliness, I am now convinced, is much more important for an appreciation of Tori Amos than beauty, though both are always present. On Boys for Pele, their very coexistence is what disgusts. For a woman to be ugly in a way that’s not readable as rebellious, or punk, or cool – ugly in a way that, because of its proximity to the remnants of beauty, reminds you all the time of your potential failure to be the right kind of woman, to be any kind of woman at all – ugly because trying too hard, overflowing, whining and gibbering, too much – not a scream, but a broken soprano – not an abortion, but a pig hanging off a porcelain breast – is worse than tasteless. It’s disgusting.

What if disgust were something every woman had to navigate in order to access the idea of taste – in music, in art, and in life? What if an aesthetics of disgust could show us that what we despise in others is actually something we fear within ourselves – and, with the dreadful, frightening persistence of the disgusting, teach us to love it?”.

I do think that it is important to bring in the entirety of this feature from CRACK. Not to pull things back to Kate Bush, though the critical reaction for Boys for Pele reminds one of The Dreaming. That 1982 album, where Bush was more experimental and it was a real departure, did horrify her label and many critics. I am not sure if Amos was channelling that but, like The Dreaming, the influence of Boys for Pele is huge. This retrospective feature argues how Boys for Pele is the misunderstood magnus opus from Tor Amos:

“On its release at the start of 1996, Tori Amos’ third album was met with responses that ranged from bafflement to outright derision within the music industry. It was the follow-up to 1994’s Under the Pink, a transatlantic best-seller that had spawned a breakthrough radio hit in the whimsically catchy Cornflake Girl. But instead of building on this, Amos had delivered a dark, uncompromising 70-minute opus in which she had stripped her music down and her soul bare – while almost entirely abandoning traditional pop song structure and lyrical directness.

Amos’ label, Atlantic, were horrified; critics, sensing that she had escaped the “confessional singer-songwriter” pigeonhole but unable to pin down exactly where she had gone, lashed out in confusion by dismissing the album as “self-indulgent” and “obtuse”. Throughout the first two months of her world tour to promote Boys for Pele, Amos has said that she was told to cancel her shows and go back into the studio.

Ploughing on was an act of faith in a record so raw that Amos would describe it as a “blood-letting”. The collapse of her relationship with former co-producer Eric Rosse had informed much of its genesis, but the fire of Amos’ cathartic rage was as rapacious as the Hawaiian volcano goddess who gave the album its title. Boys for Pele is nothing short of a full-scale purge of patriarchal repression aimed squarely at its sources of power – religion, history, politics, community – manifest in music which is both the sparsest and most confrontational of her career.

All of this makes it easy to cast Boys for Pele as a difficult record, but the actual listening experience is more complex. It’s an album of extremes, often within the same song, but Amos veers between them with such ease and command that she elides any real distinction between ugly and pretty, soft and hard. The baroque stateliness of Blood Roses is ripped through the middle by the full force of Amos’ latent Diamanda Galás tendencies. A visceral howl of pain gives way to dreamy delicacy, culminating in an astonishing set of triple rounds, on Father Lucifer. Paring her arrangements back for the bulk of the album serves only to expand her range, which takes in thrash harpsichord backed by a sampled bull roaring (Professional Widow), piano tearjerkers that could be standards in a different context (Hey Jupiter, Putting the Damage On) and, briefly, the mimicking of a daytime TV theme tune on a song declaring Jesus to be a woman (Muhammad My Friend) – probably the outright funniest moment of Amos’ career.

Some of Boys for Pele’s ostensibly most forbidding aspects prove to be its most inviting. Experimental song structures simply end up giving Amos’ underrated gift for melody more room to shine: Boys for Pele is secretly one of her most hook-rich works, but the way in which they flow into each other is entirely in keeping with the album’s shifting sands building its own strange internal logic. The same is true of Amos’ lyricism: a stream of consciousness that moves with no explanation between mythological references, startlingly raw imagery, literary allusions, private in-jokes, wordplay that exists only for the pure phonetic hell of it, parsing meaning from any given song is to open a door to many worlds. Amos has been reductively labelled a “confessional” artist, but the oblique nature of her songwriting is a dismantling of the idea that piecing together a straightforward “confession” is a useful goal; rather, Amos communicates the fragmented, blurry nature of trauma in her words and unvarnished emotion in her voice.

Twenty-five years on, Amos largely remains an artist given her due by real heads only. Her position in the canon – such as it is – has not been the result of any large-scale critical re-evaluation, and unlike many of her peers from the 90s rock landscape she has never been deemed a cool touchstone by the music press: her piano perceived as too polite at a time when grunge was in vogue, her virtuoso theatricality an ill fit for a turn-of-the-century indie scene that prized lo-fi mumbling, her earnest feelings a turn-off to generations of critics who have preferred to seek refuge in jaded irony.

Instead, Amos has been a cult artist, a term that may have been once commonly used in the music press to disparage her notoriously devoted fanbase – uncoincidentally, one that skewed heavily female and/or queer – but should instead be a reflection of a rare gift to create the kind of human connection with an audience that is arguably the entire point of art. The past decade has seen elements of Amos’ aesthetic quietly return to prominence, thanks in part to self-avowed fans from Taylor Swift to Perfume Genius to St Vincent. But few comparisons survive much interrogation: Bat for Lashes and Joanna Newsom, for example, bear much the same relationship to Amos as she did to Kate Bush, the point of reference continually and lazily thrown at her by critics unable to hear beyond a shared instrument and vocal range.

Indeed, the best comparison points to Boys for Pele in recent years have been albums that sounded nothing like it, by artists working in entirely different genres. Angel Haze’s 2015 album Back to the Woods turned emotional wounds and religious trauma into a source of power in a similarly cathartic fashion, manifest in Haze’s furiously confrontational rapping and bone-juddering percussion; while electronic R&B visionary Dawn Richard’s headiest experiment yet, 2013’s Blackheart, was also a triumph of inventing its own internal logic. Both, appropriately, are also cult classics that exist on the margins rather than mainstream breakthroughs. Amos’ legacy is as an entirely sui generis artist with an unparalleled ability to strike the realest of chords in the most unpredictable of ways – and Boys for Pele is her most unreplicable work”.

I am going to end with a review from Pitchfork. In 2016, twenty years after Boys for Pele was released, Tori Amos reflected on the album with Stereogum. She also premiered the B-side, Amazing Grace/Til The Chicken. In a year that saw epic releases from Beck, Manic Street Preachers, Kula Shaker, DJ Shadow, Fugees and Suede, I do think that Boys for Pele fits into the year and what was popular. Maybe some critical backlash was less about what the album sounded like and how long it was. Perhaps more misogyny towards a woman who was pushing boundaries and going beyond the Pop mainstream:

“STEREOGUM: Boys For Pele ended up being a turning point in your career. What was going on in your life leading up to the making of this album?

TORI AMOS: I’d been on tour for a long time in 1994 for Under The Pink. We had gone to so many different places and I met so many different people. We had a full crew out there then and that was different for me, because before that it was just an engineer and my tour manager, just the three of us. Then I had a proper crew and they sort of became, I don't know, my band [Laughs] and I became friends with them all. It was a mixed bunch. There were some Brits. There were some Americans. My tour manager was British and the reason this matters is because of Mark (Hawley) and Marcel (van Limbeek), Mark was sound and Marcel was my monitor engineer, and they had worked together in the past. It was just working out really well with them on tour. By October, Mark and I began dating but we had hardly ever really spoken before the tour... It's funny that you and I are talking right now. What's today's date?

STEREOGUM: Under The Pink was a pretty big hit. I’m sure the record label was like "just do some more of that," or wanted to put you in the studio with Rick Rubin or someone like that who can make something palatable to the mainstream, but instead you came out with this record that was more dense and difficult, but great in its own way. What did the record label first think when it first heard it? Were they happy, or like “hmmm...”?

AMOS: Oh my God, it was played in New York and I don’t sit in during the listening sessions, so I was just out to dinner, but not partying or anything, and I walk in and say hi to everybody and it was being played in the recording studio in New York and Mark and Marcel were there in the control room. My God, I’ve never met such frosty reception in my life! [Laughs] I guess I had a frosty reception once with (former band) Y Kant Tori Read. I have had rough receptions, but I just was not expecting the look on people’s faces. I can’t even tell you what it was like. It was really just vicious, the most shocking, awful things you could hear from people. Only the classical music department got it.

STEREOGUM: Did you have to fight to release it the way that you wanted it or did they want you to go back in the studio and cut a few more hit singles or something?

AMOS: By that time, the discussions had already happened. That album was already coming out. I had been warned. I had been warned. But the champion of this record was the legendary Bob Ludwig who mastered it, and he did the remaster. He looked at me and said: “This is the record of your career.” He said that other artists have done this in their career, sometimes later and not on their third record or this early, but it’s respected. It’s raw. He came to understand that about it.

STEREOGUM: You’ve had angry songs on your albums before like “The Waitress,” but for this one we have “Professional Widow” and “Caught A Lite Sneeze,” which is you at your most visceral, in a way. Where did that anger come from?

AMOS: I don’t know, thirty years of processing. I don’t know. Maybe it was about control. Maybe it was about a trigger that I sensed or was happening when people wanted more of the same and I don’t mean... I’m not talking about just hits. I had a great relationship with (former Atlantic Records executives) Doug Morris and Max Hole. They were like my fathers. No that’s not right, they were like mentors. They broke Little Earthquakes, and Doug had been locked out of Atlantic Records, and I say when he left, he’ll correct me and say: “Tori, they threw me out of the building, who are you kidding?” He had to start again, and boy did he start again. He is probably one of the most legendary record men that has ever lived. And listen, I understand with the new people at Atlantic, I understand how this record would just be “what?” after Under The Pink. And the promo people... I get it Michael, I get it. But if you look at it in the way you said before, there's a tradition where any artist that will be around for 20 years will have to make this kind of record at some time.

STEREOGUM: Some of the early reviews were kind of harsh. Wasn't the Rolling Stone review a pretty bad pan?

AMOS: Fuck you, critic at Rolling Stone. Next.

STEREOGUM: It’s interesting, because eventually the album caught on and you started getting a lot of rotation at rock stations. You heard “Caught A Lite Sneeze” and “Hey Jupiter” all the time if you were paying attention back then. Did you notice you were reaching different people and getting into a different strata after that album?

AMOS: Yeah, the audience got a lot younger. A lot of teenage girls started showing up. A lot. Before, I had a lot of heterosexual men in their thirties, and some women of course. But something with this record really kicked in. And the gays were always there. They have always been there. Without the gays, I am nothing. Men and women, I am talking about. But really they were the best, they were just there from day one.

STEREOGUM: What was it about this album that got the teen girls, finally?

AMOS: Well, you know, I didn't set out to do it, but I think that “Me And A Gun” and “Silent All These Years” did speak to people of all ages, but I think there was a kind of... This is how it has been described to me by people over the years; that some of them were 13 years old, 15 years old in their room, listening and experiencing similar emotions of not being able to express that feeling of being controlled by their parents, or their life feeling out of control. They didn't have control of their life. So hearing Tori quote-unquote rationalize that at the time after having a successful couple of records and carving a path that people maybe didn't think she should carve because they knew best about what she should do, and standing up against that was something that they really identified with. It’s kind of like when your parents are telling you: “No, you want to do this, you want to go to college and you want to be that and we’re doing this because we love you.” And you feel like saying: “No, you’re doing this for you. You’re not doing this for me.”

STEREOGUM: Obviously you’re at such different place in your life with your marriage and your daughter and you seem very happy. Do you recognize the woman singing these songs anymore, or does it seem like a completely different person?

AMOS: I recognize her, because I wouldn't be here without her. I recognize her. But I don't know if Tash would want her to be her mother. To be where I am right now and to be chill and to be laid-back, but still present and clear and a decent listener, I had to make some changes in my life and I had to confront some stuff. I had to confront the idea of mending, and control of my life, whether it was corporate or the industry, whether it was my dad, whether it was whomever. I thought, “No, I have to be an equal in my life” as far as not just performing and writing and being the type of artist people want me to be. That, to me, is not honest. That, to me, is you aren't responding as a songwriter to what is happening in front of you today and writing about that. See, what you’re doing is not fabricating, but you’re creating in a way that everybody has agreed is acceptable, and, to me, that is not a liberated woman. A liberated woman who happens to be a songwriter says, “No, I need to write some truthful space,” whatever that truth is at the time”.

I love all of Tori Amos’s albums, though I have dim memories of Boys for Pele at the time. In January 1996 I was twelve, and I was more into Britpop and stuff coming out from my native land (the U.K.). I was well aware of Tori Amos, but tracks like Professional Widow really opened my eyes. It was so different to anything I had heard before. In terms of its themes and lyrics, it perhaps caught some unaware. The Pitchfork review properly salutes a divisive third album that is “a strange and unsettling amalgam of distorted harpsichord and bloody revenge fantasies born of ayahuasca, Mary Magdalene, and the blues”:

“On top of its nonsense lyrics, Boys for Pele also offers little respite from the harpsichord. In keeping with her quest for provenance, Amos traced the piano’s bloodline to its plectrum-equipped ancestor—an instrument she swiftly became obsessed with, despite its scant melodic or textural range, and, more crucially for Amos, its lack of sustain. For someone who pumps her piano’s sustain pedal as if she’s trying to resuscitate the notes back to life, Amos was severely tested by the harpsichord’s constraints. “I wasn’t interested in anything that didn’t challenge me, and as I started finding different parts of myself, I brought in different instruments to express that,” she explained to Spin. The greatest challenge with the harpsichord was to cleave it from its Baroque associations. She wanted to take out the whimsy and give it some ass. To do that, she made the low end growl by feeding a Bösendorfer piano through a Marshall amp . You can hear the rusty buzz and rattle of each of its keys. For Amos, compression was the ultimate taboo.

Amos referred to Boys for Pele as her “thrash harpsichord” record, a descriptor most befitting of two songs: “Professional Widow” and “Blood Roses.” She plays the former in an unnervingly standard waltz time, with parallel fifths that she smashes to smithereens in every other measure. On “Blood Roses,” she growls, “Chickens get a taste of your meat, girl,” alluding to a scene in Alice Walker’s Possessing the Secret of Joy in which the byproducts of female mutilation are tossed to the birds. On the harpsichord, she jounces between rapid-fire triplets and largo sequences, all while traveling across scales so swiftly it inspires the awe and horror of watching someone tap dance themselves into flight. She discovers the instrument’s blood.

Amos’ quest for provenance is also reflected in her deliberate choice of recording locations: a deconsecrated church in County Wicklow, Ireland, and a studio in New Orleans, Louisiana. Boys for Pele, with its bluesy tones and syncopations, re-synthesizes the influences that make up the musical identity of the rural South. She draws particular attention to the way Irish music made its way through the rivers of Louisiana in the 19th century, influencing the blues and the region’s cultural sound. “Mr. Zebra,” with its bouncy piano line, has the feeling of a slip jig; “Horses” rolls in non-linear arpeggios like an Irish air. Boys for Pele is a spiritual as well as musicological investigation of place.

To Amos, these sites symbolized, more specifically, the New World church’s stripping of Mary Magdalene’s sacred sexuality. Much of Amos’ musical project has long revolved around recovering Magdalene’s legacy—a legacy the modern church had reduced from Jesus’ bride to an unrepentant sinner. “If we were going to use a term to describe my music, it would have to be ‘theology of the feminine’,” Amos told The Oregonian in 1996. She believed not only that Mary Magdalene was pregnant with Jesus’ child but that this buried truth formed the blueprint for all women’s sexual culture—and that had the original myth remained intact, Amos would have been raised with a healthier relationship to her sexuality, to men, and to herself. Boys for Pele is her attempt to violently write into existence the sacred Bride that Christian theology has long obscured.

These ideas were so heady that Amos was never quite able to synthesize them into talking points during Boys for Pele’s lengthy press run. Many of the interviews instead concerned Amos’ relationship with the internet, a hot-button topic at the time. A curiously under-remarked aspect of Boys for Pele is how much the internet contributed to its success. Though Amos had touched a computer maybe twice in her life up to that point, she had an unusually devout online following. Her fans were very early adopters. Digital mailing lists devoted to Amos even preceded the World Wide Web as it came to be known, with some fans sending out digests on a daily basis in the early ’90s.

With the dot-com boom, a flurry of Amos fan sites emerged, including the First International Church of Tori, with its own dedicated “Altar Room.” At the time of Boys for Pele’s release, there were some 70 websites devoted to Amos—an extraordinary amount for that nascent era of the internet—and Amos supported those sites by giving them exclusive interviews. Atlantic Records cleverly tapped into the new niche by making “Caught a Lite Sneeze,” the album’s lead single, one of the world’s first songs to premiere as a free digital download ahead of its official release. Amos’ website also debuted samples of three Pele tracks on December 15, 1995, and upon the album’s release a month later, the Atlantic Records website scored two million hits, their most in a single day.

At school, Amos, a self-proclaimed nerd, was voted homecoming queen by the school’s nerd committee. This is sort of how her fame worked then and still does today. Despite significantly less radio play than her previous two records, Boys for Pele achieved platinum status much faster than its predecessors. The album debuted on the Billboard Hot 100 at No. 2, held from the top spot only by the unmovable Waiting to Exhale soundtrack. Her extensive 187-stop Dew Drop Inn Tour, running from February 23 to November 11, 1996, sold out within days and grossed $4.4 million, making it one of the highest-earning ticket sales of the spring.

Amos’ reputation and fame in the ’90s did not carry into the new millennium quite the way it had for her contemporaries Björk and PJ Harvey. She didn’t possess either’s sanguine cool. Before Amos made it as a musician, she’d ousted Sarah Jessica-Parker for a role in a Kellogg’s commercial. The director told her she did a good job, but to “tone it down please.” Instead, Amos toned it up for the rest of her career, transforming herself into a meta-Jungian girlband for 2007’s American Doll Posse and caressing herself onstage with a knife.

Even today, Boys for Pele remains the most distinctive record in her discography. Amos embodied such an extreme scope of emotion that it fell outside any frameworks capable of packaging or aestheticizing it. While other exceptional women of the ’90s transmuted their rage into power, Amos did something more akin to turning excrement into ecstasy, delivering her rage with a barnyard stench. It was an absolutely monumental achievement, a dive into another world from which no sound could escape. On Boys for Pele, Amos truly came undone, un-disciplining music while disassembling the spirit. She was convulsing, untouchable, and often illegible. Mystical Christianity dictates that this kind of abjection is a sign of close proximity to the divine, but on Boys for Pele, there was no God to be found”.

I think that Boys for Pele is a masterpiece and the third in a perfect run from Tori Amos. She would follow 1996’s Boys for Pele with 1998’s from the choirgirl hotel. Not to bring it once more back to Kate Bush, but perhaps there was a feeling that, after an album that divided critics but was a commercial success, some compromise was needed for the next album. Amos’s fourth album was acclaimed and ‘won back’ a lot of people. NME wrote how “The kookiness isn't dominant, she's stopped the attention-seeking lyrics almost completely and, yes, her pianos don't try to be guitars too often…At last, she's putting the songs first, and the band-led From the Choirgirl Hotel is, by any reasonable yardstick, a glorious coming of age”. I think that there was a lot of sexism and misogyny that meant women had to record certain music and could not be different and slightly experimental. Boys for Pele turns thirty on 22nd January. I wonder whether Tori Amos will mark it or write something about one of the best, and most underrated, albums of the 1990s. There is a line from Professional Widow, the third single (it was a U.S.-only single) from Boys for Pele, that seems to sum up the album, or is a mission statement from Amos: “What is termed a landslide of principle”. The glorious, pioneering, hugely intelligent, beautiful and raw Boys for Pele is…

A sublime and fascinating album.