FEATURE:

I’m the Fear Addicted

The Prodigy's Firestarter at Thirty

__________

ONE of the…

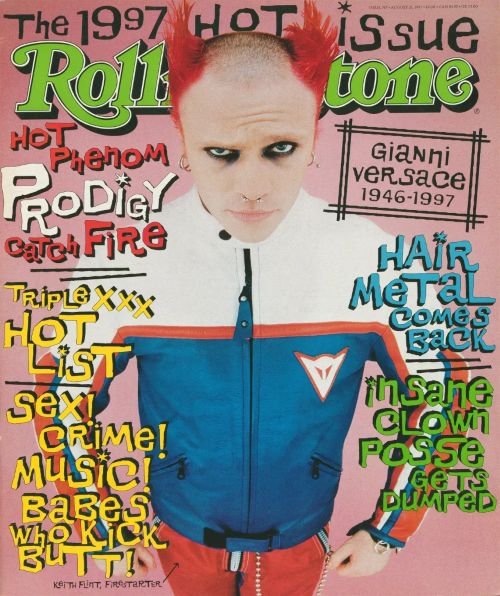

most important and highest singles of the 1990s was released on 18th March, 1996. The lead single from The Prodigy’s third studio album, The Fat of the Land, was like an explosion! A song that still resounds to this day. A song that has credited writers of Liam Howlett, Keith Flint, Kim Deal, Anne Dudley, Trevor Horn, Gary Langan, Jonathan Jeczalik and Paul Morley, Firestarter reached the top of the charts in the U.K. Because the song turns thirty soon, I am focusing on, for the most part, its creation and legacy. I will end with a 2020 feature from The Guardian. They placed it eighth in the list of the one-hundred greatest U.K. number one singles. A song that is defined by the electrifying and distinct vocals of the much missed Keith Flint, I remember when Firestarter came out. It was a revelation. This was the first timer Flint provided vocals for The Prodigy. More of a dancer with the group prior to that, he knew this was the song he had to sing on. Writing these incredible lyrics and so committed to working on the music video and making it as unforgettable as possible, Firestarter is one of the defining tracks of the 1990s. I want to highlight a 1997 Rolling Stone cover, which has this sub-headline: “How a faceless ass-rumbling hard rock techno band found a voice (and a haircut) and set the world on fire”. I wanted to highlight the sections below, as we learn how Keith Flint being from someone in the background for The Prodigy to being at the front. He would also sing on another The Fat of the Land single, Breathe, but Firestarter is his finest moment. The best song he ever put his vocals to:

“Before “Firestarter,” the only singing that anyone had heard Keith Flint do was the routine he and Thornhill would sometimes perform, bored, in the back of the tour van: crooning U2’s “One” as they waved their lighted-up mobile phones in the dark, pretending they were lighters. But Howlett had this instrumental, and Flint announced one day that he’d like to try doing something over the top. They wrote the lyrics together. Howlett thinks he came up with the “Firestarter” idea and masterminded the structure. The words are simply a picture of Flint. “He’s got not a cent of common sense, but he’s actually really intelligent,” says Howlett. ” ‘I’m the self-inflicted mind detonator’ — that’s him. He’ll build things up in his head until he’s on the edge of going mad. That lyric was spot-on.”

Flint highlights both the “self-inflicted” line and “I’m the bitch you hated.” They’re both ways that he thinks of himself. “It’s quite deep,” he mutters. “I don’t know if I want to say.” He eyes the tape recorder. “I could explain it to you, but I wouldn’t for the magazine.”

Listening to you spit out those words, I say, you get the feeling of energy and joy mixed up with self-hate.

“That’s absolutely spot-on. That’s absolutely spot-on.”

I’m the bitch you hated. That’s a very weird thing to say about yourself.

“Yeah. I don’t know that I’d want to describe it,” he says. “That is a very deep thing to me personally, and I can deliver that with far more power than the other lyrics.”

Why, suddenly, did you decide to write lyrics?

“That’s unexplainable,” he says. “Why does a river turn into an oxbow lake? I’ve spent six years expressing myself with my body, shouting with my body. It’s like a conductor of the music. From the party scene, when a tune came on and it was your tune, I wanted everyone to know it was my tune. Yes! Fuckin’ hell! Rockin’! Just yelling at each other, dancing away. This is just an extension of that. If I could get a mike and just go, ‘Fuckin’ hell! Fuckin’ hell!’ I would do it. That is the punk-attitude, DIY aspect of the Prodigy.” And this was an age of change for Flint. The nose bolt. The pierced tongue. The new hair. “Fuck it,” he reasons. “I’m in a band. I’ll do what I want.” He worries that it’s becoming too much. An image. He might dye his hair all black. (He wants to get his penis pierced, partly because that one will be just for him. That’s one that will not be on display.) He also got inflicted tattooed onto his stomach. He got Howlett to design the letters. Inflicted. It was saying what people were thinking when they looked at him.

The night that Flint and Howlett wrote “Firestarter,” they played it about 30 times in the car. “I don’t think either of us could quite believe it was me,” says Flint. “I’m not a singer. I love the fact that there’s people out there that have been trying since the age of 9 to sing and get the voice right — do, re, mi and all that — and I can roar in, not ever written anything or performed lyrically anything, and write a tune that’s so successful. I think that’s a brilliant piss take on a lot of people, and that gives me a buzz.”

It was the video that best communicated the hyperactive psychosis of “Firestarter”: Flint leaping and leering around in a disused London subway tunnel. It is said that when it aired on Top of the Pops, Britain’s most-watched music TV show got a record number of complaints, simply because Flint was so scary”.

The Fat of the Land received some huge reviews when it was released on 30th June, 1997. If there are problematic songs on it such as Smack My Bitch Up (which many saw as glorifying domestic abuse and being misogynistic), there are some underrated classics like Diesel Power. Breathe is the second single, and I always see it as too similar to Firestarter. A slightly inferior version. It is weird that Firestarter is track eight on The Fat of the Land and not nearer the top. It does sort of get buried towards the end when it should have been the lead track or the second one. However, it has this incredible legacy. It created shockwaves and tremors when it came out on 18th March, 1996. Over a year before the album arrived, fans of The Prodigy were realising why Keith Flint should be front and centre. His lyrics and incredible vocals, tied to his distinct look, huge energy and infectiousness – and some chaos into the mix! – helped bring the band to a new audience. I was one of those people who became a convert in 1996. There are two features I want to include before wrapping up. The Delete Bin reviewed Firestarter in 2015. They have some interesting takes. I forgot about the furore and controversy the song caused. Especially the video. It does seem insane that thee was this sensitivity around a song that was not exactly urging people to start fires or incite destruction and violence:

“The Prodigy were dogged with controversy over many aspects of their presentation and their content. With this song, maybe controversy was stirred up because of the video, and the meaning of what a “firestarter” really is, too.

Controversy aside for moment, the reason I think that this song, and the album off of which it came, was so popular is because it provided a series of varied musical textures that Brit-pop guitar bands didn’t provide, while still managing to reflect the guts of rock music which so many guitar bands were trying to capture in a new paradigm. The first time I heard this, I didn’t really process it as dance music. To me, it was punk rock. Maybe this is because it sampled the Breeders. But, there was more to it than that.

Not too many dissenting critics took into consideration that “fire” as a concept isn’t necessarily about destruction, or pain, or murder, or hell, or whatever. Fire is about creativity, too. Think about Prometheus in Greek myth. And about “holy tongues of fire” in the book of Acts in the Bible. Fire is a classic double-edged sword in storytelling. It can be destructive. But, it can be used as a literary device, emblematic of a force that sweeps away the old to make way for something new. It can be about inspiration and about clean slates. That’s what I think the band were really driving at, and what really makes this song as punk rock as it is.

As Flint spits out “I’m the firestarter!” all punked up and full of feral and wide-eyed fervour as he is in the video, he seemed like some Anti-Christ figure to some, maybe. It followed that a lot of people just took it all at face value. But in the song, he also asserts “You’re the firestarter!” which seems to undercut all that, not that too many people noticed. As such, this tune is actually pretty empowering. It’s the dance-rock, punk rock expression of Ghandi’s “be the change”. Or at least that’s certainly one fair interpretation, and certainly an example that makes it important to always question the wisdom of most decisions that lead to bans on things in the name of public decency”.

I am going to visit NME’s 1996 article. They followed The Prodigy on the set of Firestarter. As they say in this revisit (published in 2019): sensitivity: “Please be aware that sensitivities may have changed since publication”. This unfiltered band that wanted to definitely shake things up and ruffle some feathers, it did seem like it was a handful being around them! However, by all accounts, the band were perfectly amiable. Especially Keith Flint. A lot different to the impression people had of him. Definitely after the Firestarter video:

“People say Keith looks insane these days,” shrugs Liam, during a break from overseeing the filming.

“But he’s been insane for five years! He was insane the day I met him dancing in The Barn in Braintree. People only started to notice when he dyed his hair. And obviously the press and the fans are going to latch onto him now. But it was always going to be like that. It’s a natural progression.”

His public profile is surely set to go ballistic in about two weeks, though, in the wake of his starring role on ‘Firestarter’. And Liam may not be responsible for the ensuing carnage.

“I recorded it as an instrumental,” recalls Liam.

“And as usual, all three of the others come round to have a listen. Keith happened to be the first, and I said to him, ‘We need one more element’. Now I’d have been happy with a good sample, but Keith says, I’d really like to try some vocals on that’. And I’m like, ‘Whaaaaaaat?!”

“We had no idea how it was gonna sound,” admits Keith, “because the only singing Liam’s ever heard from us is me and Leeroy singing U2 songs on the way home. We always harmonise on ‘One,’ and instead of lighters, we put up our mobile phones and wave ‘em in the air!

“It was so ridiculous because my English isn’t my strong point, by any stretch of the imagination. So I end up singing in this weird accent (puts on a daft yokel voice), ‘Oi’m a muckspreaderrrrr, twisted muckspreaderrrr’. But it ended up sounding quite… menacing.”

So are we to assume that ‘Firestarter’ is autobiographical, then? Have you burnt down any houses lately?

“Oh no, man!” counters Keith. It’s never that direct. It does make you think though. They played the white label at Stamford Bridge the other day, and I was thinking, ‘I hope it don’t start any Bradford fires!”

“Leeroy knows me inside out, though,” he concludes, “and when he heard it he said, ‘That tune sums you up, man’. So there you go.”

This is the second video The Prodigy have made for ‘Firestarter’. The first one was directed by the man responsible for a Mustang jeans ad the band liked. “It didn’t represent us properly,” according to Liam. Which roughly translates as, “We were barely even in it”. Presentation and representation are a high priority, some might say absurdly high, for The Prodigy, possibly the only successful band in Britain who refuse to appear on Top of the Pops or, indeed, most other TV programmes. It’s not a ‘real vibe’ is their usual argument. But Keith, inevitably, has something more to say. And there could be casualties.

“TV corrupts people, I think. A lot of acts get that little break and they change from T-shirt and shorts to designer stuff, swanning around like arseholes. I mean, to me Goldie and Björk are like that. Goldie’s coming on as the bad boy of the jungle scene — and then next thing you know he’s going on to give an award to his girlfriend at The Brit Awards. Now to me, that was as sickening as Michael Jackson and Lisa Marie Presley. I’m not dissing him, right, but if I watch that, it’s Bon Jovi. It’s Hollywood. You give ‘em a few front covers and they wanna play the pop-star game.”

“Nah, that’s bollocks, Keith,” Liam calmly corrects his colleague. I’ve got respect for Goldie, because all he’s doing is bringing a music that’s actually quite small – ’cos jungle’s not as big as the press make it out to be – to a new audience. He hasn’t commercialised his music. And he hasn’t sold out. It’s good stuff man.”

“Sure,” says Keith, slowly trying to dig himself out of the the hole his big mouth has created. “But I’m just saying, you put a camera in front of someone and they do something a little bit cheesy. It’s just the hypocrisy, man. If you slag off the mainstream when you’re small, you shouldn’t embrace it later.”

Never mind. I hear Goldie takes criticism with good grace.

Bit of a shame about Top Of The Pops, though. Just imagine the nationwide tea-choking that would doubtless be introduced by Keith Prodigy breaking and entering your living room at 7pm on a Thursday evening…”.

I know 18th March is a little way away, but I wanted to be the first to mark thirty years of Firestarter. There will be anniversary celebrations coming soon enough. It is bittersweet as we lost Keith Flint in 2019. He is not around to see those words published. How people are responding to the song today. Firestarter still sounds like nothing else! I think it is the best thing The Prodigy ever did. A Molotov cocktail of a song where Flint seems fevered, hallucinatory and raving, his lyrics are genius. His performance is iconic.

IN THIS PHOTO: The Prodigy’s Keith Flint performing at the Phoenix Festival in 1996/PHOTO CREDIT: Mick Hutson/Getty Images

I am ending with The Guardian and their article from 2020. When deciding the best one-hundred U.K. number ones in 2020, Firestarter was placed in eighth. A huge recognition of its legacy and importance. Revolutionary and still so powerful to this day:

“It starts with a riff: not a distorted guitar but a contorted squeal from a twisted fairground. It’s a riff nonetheless, the instantly sticky sign of an unstoppable hit single. Firestarter was one of the biggest pop-cultural events of 1996 and by the end of the year the Prodigy were one of the world’s biggest bands. The Essex four-piece’s first No 1 was a flashpoint of teen angst, TV infamy, moral panic and tabloid outrage, carried aloft by big-beat pyrotechnics and a lethal barrage of lyrical vitriol. “Ban This Sick Fire Record,” squawked the Mail on Sunday – but it was much too late.

The Prodigy were already a dominant force in pop. All but one of their singles since 1991 had made the Top 15, including 1991’s Charly, the cartoon-sampling hit that famously “killed rave”, according to clubbers’ bible Mixmag. Liam Howlett, the band’s musical engine, was bored with cranking out rave hits to a formula and started experimenting with elements of hip-hop and rock on their second album, Music for the Jilted Generation. Now the Prodigy were ready to reintroduce themselves as stadium-sized heroes with The Fat of the Land, taking dance music deep into the moshpit while promoting dancer-cum-hypeman Keith Flint to songwriter and vocalist. As an opening salvo, Firestarter was flamboyant, surreal, terrifying – and, like all the best pop songs, totally novel.

I have a faint recollection of watching Firestarter on Top of the Pops that week. The Prodigy didn’t want to perform, adamant that their anarchic live energy wouldn’t translate to the nation’s living rooms, so after Gina G and PJ & Duncan had done their thing, the BBC exposed millions of young minds to the video, depicting a diabolical figure in a reverse mohican twitching and gurning like a thing possessed. Too young to have any context for the music, I was transfixed but repelled, vaguely aware that this was something I probably shouldn’t be seeing.

That scuzzy black and white clip, filmed in a disused tube tunnel, was Firestarter’s second video, produced on a shoestring after the Prodigy had blown £100,000 on a hated first attempt. Flint flicks his pierced tongue at the camera, eyeballs glowing against his black eyeliner. The Prodigy came from the rave scene but this was more Marilyn Manson than Orbital, and Flint was a tortured rock god, snarling lyrics about mental anguish and self-harm: “I’m the self-inflicted mind detonator / I’m the bitch you hated, filth infatuated.”

The music press had been building them up as the “electronica” act that could finally crack the US, but the Prodigy didn’t see themselves in that lineage. They weren’t avant-garde like Aphex Twin and Autechre, and they weren’t purveyors of what rock writers liked to call “faceless techno bollocks”. Firestarter proved that the Prodigy was a squirming, sweating, fleshbound beast – the very opposite of the futuristic “braindance” coming from the electronic vanguard. It was pure boiling animus, doused in petrol and set off to ruin someone’s birthday party. “I have a philosophy that most of our music works on a really dumb level,” said Howlett, “which is the level most people understand.”

He imagined the Prodigy as a stadium-filling spectacle on a level with the rock bands such as Red Hot Chili Peppers and proto-nu-metallers Biohazard. “No glow sticks, no Vicks, people spitting everywhere – brilliant,” as Flint put it. They even brought in spiky-haired guitarist Gizz Butt, who’d played in early punk bands such as the Destructors and English Dogs. But where so many rock-historical references of the mid-90s felt like cosy nostalgia, Firestarter squeezed a final gob of spit from the spirit of 77 while becoming a legitimate stadium-sized alternative to Oasis. The Gallaghers so desperately wanted to be adored. The Prodigy didn’t give a toss. Howlett’s harsh sample collisions (a vocal scrap saying “hey”, from the Art of Noise’s Close to the Edit, and that squealing riff, pinched from the Breeders’ SOS) reflect his roots as a hip-hop DJ and breakdancer, but although he took production cues from righteous outfits including Rage Against the Machine and Public Enemy, he wasn’t interested in their message.

Firestarter doesn’t care about anything, nor does it contain a shred of self-regard. When Flint brought his “twisted” persona to life, he aligned himself with a 90s seam of edginess that brought us Fight Club, Tank Girl and Scream. It’s strange to imagine that we gawped and laughed. The decade’s flippant treatment of “insanity” is risible now, and especially tragic after Flint’s death in 2019. Journalists compared him to cartoon characters, but in those lyrics he is nothing but human. Firestarter is the worst of us, splattered on the kerb for all to see. “I wasn’t trying to say, ‘look at me, I’m Satan!’ But certainly I’m not nice,” Flint told Q magazine. “We’re everybody’s dark side”.

I was completely in awe of this song when it came out in 1996. I was twelve and had heard nothing quite like it. The extraordinary and seismic lead single from 1997’s The Fat of the Land, there is no doubt Firestarter is one of the most important and groundbreaking…

SINGLES of the '90s.