FEATURE:

Then Work Came and Made Us Free

Manic Street Preachers’ A Design for Life at Thirty

__________

THIS is undoubtably…

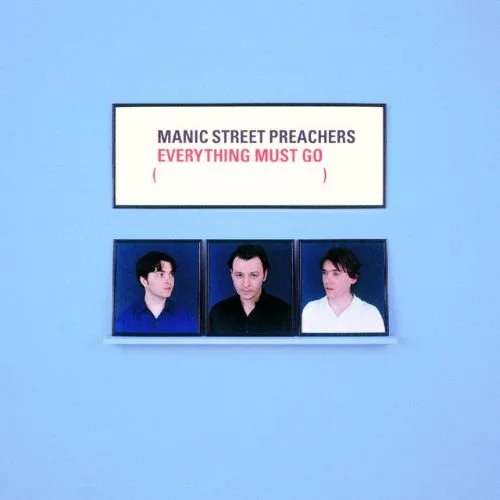

IN THIS PHOTO: Manic Street Preachers’ Nicky Wire (left), James Dean Bradfield and Sean Moore in 1996, shot for the cover of Melody Maker/PHOTO CREDIT: Tom Sheehan

one of the most important songs of the 1990s. The lead single from Manic Street Preachers’ fourth studio album, Everything Must Go, this was the first without Richey Edwards. He went missing in February 1995. It was a huge shock for the band. Not only Manic Street Preachers’ lyricist and rhythm guitarist, he was also a dear friend. You can feel the stress and tragedy of his loss on Everything Must Go. Some of his lyrics appear, whilst other songs talk about the Welsh band making changes and dealing with this loss. On 15th April, A Design for Life was released. It is one of Manic Street Preachers’ greatest songs. This towering with the trio (James Dean Bradfield, Sean Moore, Nicky Wire) credit as songwriters, it reached number two in the U.K. Everything Must Go was released in May 1996 and was a massive critical and commercial success. Its lead single is one of the best lead singles ever. Not only announcing this new direction and sound – a slightly shift from 1994’s The Holy Bible -, it is a song that is widely played to this day. Such stunning lyrics that are so thought-provoking. As this stunning song turns thirty on 15th April, I want to explore it and understand the background/history of the song. I am starting out with a 2014 article from God Is in the TV:

“Libraries gave us power/Then work came and made us free/What price now for a shallow piece of dignity?!” Hollers James Dean Bradfield impassioned with eyes closed, above a backdrop of tumbling arpeggios, cavernous drums and Spector-ish widescreen production that’s steepling strings sway, crescendo and sigh with sadness. This is the unforgettable intro to ‘A Design for Life’ the Manic Street Preacher‘s definitive 90s statement. Tackling the theme of working class identity bassist(lyricist and chief dress wearer) Nicky Wire delivers a staunch defence of the community where he grew up and a belief in the importance of resilience, self-improvement and solidarity as political power attempts to oppress you at every turn– ‘libraries gave us power’ indeed. The memorable video is intercut with quotes and scenes like fox hunting and Royal Ascot to represent what the band saw as class privilege.

This was set against a backdrop of the decimation of their hometown Blackwood, as Thatcher destroyed its mining industry in the 1980s and the economic decline of the early 1990s and many think the miners scars are referenced here with the lines: “I wish I had a bottle/Right here in my dirty face to wear the scars/To show from where I came”.

The bizarre sight of friends arm in arm singing along to its key line ‘We don’t talk about love / We only wanna get drunk’ is an ironic one – are the Manics highlighting the hypocrisy of a working class that only wants to drink and fight, or are they defending its right to do so? I’ll leave that up to you. Regardless, it’s a powerful first statement from the band as a three piece and a epic first single with a elegantly bombastic rock chorus that at the time represented a surprising shift from a band who had musically up until that point dealt only in politically charged glam rock and incendiary proto post punk. It was rather like the shift from Joy Division to New Order…

ADFL bursts to number 2 in the hit parade in 1996, and broke the three Welsh fellas’ album (Everything Must Go) into the mainstream at their time of heaviest loss. Their lyricist and childhood friend Richard James Edwards went missing in 1994 and remains unfound.

In a scene dominated by slogans, crowd like chants and sometimes cartoonish flag waving, Carry on imagery, The Manics were in contrast a band plugged into their surroundings, the working class and their own mythology ‘A Design for Life’ was an epic political statement and stands toe to toe with Pulp‘s superlative ‘Common People’ as the most socially conscious statement of the era. Nicky Wire explained the song’s meaning in an interview with Q magazine April 2011: “It was originally a two-page poem. One side was called A Pure Motive and the other A Design For Life. The song was inspired by what I perceived as the middle classes trying to hijack working-class culture. That was typified by Blur’s Girls and Boys,” the greyhound image on their Parklife cover. It was me saying, ‘This is the truth. GET IT.'”

Drenched in magnificent strings arranged by Martin Greene, and shot with a regret, defiance and a kind of redemption of somehow getting through a tragedy so close to home, the Mike Hedges-produced Everything Must Go recorded in a Normandy Chateaux, was warm and cocooned in its own orbit and quite unlike any other release that year, yet for a very short period the Manics became mainstream, Nicky draped his amp in the Welsh flag at the Brits which was surprising given his views on Wales prior to that, they played a the classic Hillsborough tribute show and rubbed shoulders with Oasis and the like. James Dean Bradfield went onto produce the likes of Northern Uproar and Kylie lending this anthemic string tinged pop sound to them both, the outsiders had become establishment.

The long player Everything Must Go was their most immediate work and struck a chord with a wider public in a way none of their previous albums had. Yet it was tinged with tragedy, regret and a new found functionalism(C&A jeans and t-shirts now replaced feather boas and eye liner)artwork now minimal, as they bravely soldiered on despite still dealing with the grief of the loss of their friend and creative driving force Richard James Edwards”.

There are a couple of interviews I am going to end with. Where Manic Street Preachers speak about A Design of Life and why it is so important. It is a song that must have been emotional to see released into the world after the disappearance of Richey Edwards the year before. I am going to move to this blog post and their examination of the sweeping, epic and wonderful A Design for Life:

“The song’s lyrics are usually thought to be themed around working class solidarity, and make specific reference to the value of libraries, which have historically allowed poorer people to learn on their own terms through books – by contrast, owning books has historically been the preserve of the educated rich (and books of course remain expensive today, particularly factual ones). This line was directly inspired by the band’s time in public libraries when they were young. The lines “we don’t talk about love / we only want to get drunk” are a play on upper class assumptions about poor people – the idea that the lives of “the proles” are dominated by idle pursuits like drinking and that they ostensibly don’t have a capacity for philosophy or independent thought. Naturally, the Manics rail against this narrow-minded idea. By contrast, the song was famously misunderstood by some at the time, who saw the song as a kind of laddish drinking anthem.

Like ‘Motorcycle Emptiness’ before it, ‘A Design For Life’ began as two songs – one written under that title designed to play up the positive aspects of working class life and another, named ‘The Pure Motive’ which was about the darker side and was inspired by ‘To Be A Somebody’, a 1994 episode of Jimmy McGovern’s crime series Cracker. In the episode, Robert Carlyle plays a killer working to avenge the deaths of those who died in the Hillsborough disaster in 1989. This event would itself be the inspiration for a later Manics track, ‘S.Y.M.M.’, the closing track on This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours. Parts of ‘The Pure Motive’ were absorbed into ‘A Design For Life’, resulting in the final version.

Owing to its major impact on popular culture, ‘A Design For Life’ was memorably referenced in the final track of The Man Who, the very successful 1999 album by Scottish band Travis. The song, ‘Slide Show’ refers to the song in the first line of its chorus, which also alludes to ‘Wonderwall’ by Oasis (which it is actually musically based on to some extent) and ‘Devil’s Haircut’ by Beck. Musically, ‘A Design For Life’ was also reflected in the Manics’ own much later single ‘Indian Summer’ – the band initially hesitated to release the song due to it sounding similar, but eventually decided to release it for exactly that reason.

Although it is arguably a little harder to enjoy now due to the enormous airplay it has received over the years, ‘A Design For Life’ is still undoubtedly one of the key Manics singles, a live staple, and a significant touchpoint in their discography”.

Before ending with a 2021 interview from the BBC, I want to flip to 2016 and this interview from The Quietus. They spoke with Manic Street Preachers in 2016, twenty years after the release of A Design for Life. I recall when the song came out. I was familiar with Manic Street Preachers at that point. I bought Everything Must Go and was completely fascinated by A Design for Life:

“I was really struck by seeing the video for ‘A Design For Life’ during the Royal Albert Hall gig, with the footage of Last Night Of The Proms, filmed in the same place, and thinking, ‘Here we are’, in the actual place…

“Here we are!” Wire smiles. “Entertain us… Yeah, the first time we played the Albert Hall, in 1996, I hated it. I was in a right old fucking mood, and I did not enjoy it one bit. But I loved it this time. The gig in Liverpool was amazing, really special, and we invited all the families of the Hillsborough 96. From the very first gig, in Tallinn in Estonia, it’s been spot-on, right through.”

A lot of the songs on the album have been in or around the setlist for years, of course.

“Yeah,” concedes James, “but there’s stuff like ‘The Girl Who Wanted To Be God’, ‘Removables’ we haven’t played that much, or ‘Interiors’, and we haven’t played ‘Australia’ much since the late Nineties, and ‘Further Away’ we haven’t played much. But you’re right, stuff like ‘No Surface All Feeling’, ‘A Design For Life’, ‘Everything Must Go’, ‘Kevin Carter’, ‘Small Black Flowers’, we’ve played the hell out of.”

“That album just breathes, sonically and lyrically,” says Wire. “It’s a communal intake with less intensity than some Manics gigs, if you know what I mean. But we ramp it up so much in the second set, with the production and the visuals which are fucking stunning. It has the scale that we always wanted. And knowing you’ve got that second set in your back pocket, doing ‘You’re Tender And You’re Tired’ which we haven’t done for fucking ever. and… ‘NatWest Barclays Midlands Lloyds’…”

When I saw ‘NatWest’ on the setlist for the second half of the gig, I thought ‘Really?!’ Of all the songs on Generation Terrorists, I’d never have chosen that one. But in the flesh, it properly rocks. I was surprised.

“I actually feel really proud doing that, as well,” says Wire. “Because you still get all these fucking idiots in the broadsheets saying ‘Oh it’s clunky…’ It IS clunky, because we’re dealing with a massive topic (the banking system’s ruinous effects on people’s lives), which we foresaw, and you didn’t!”

The choice of Mike Hedges as producer was crucial to the album’s sound. “We’d been through the thing of Richey’s disappearance,” James remembers, “and subsequently deciding that we needed to do something, so we wrote the song. ‘A Design For Life’, which started the ball rolling. Then we got in touch with Mike Hedges, who came to Cardiff with us. We’d wanted to work with him on The Holy Bible, but he wasn’t available. Meeting him was so brilliant, because he’d done so many records I loved. ‘Swimming Horses’ by the Banshees – what a fucking record that is! I remember there was a kid at school who was, let’s say, not unhinged but definitely on edge. And he’d gone goth-punk, and he brought a copy of ‘Swimming Horses’ 12 inch to school and I sat on it by mistake. And he wanted to kill me. And I remember thinking ‘You really care about that record. I’m gonna have to chase that record down…’ And Mike had also done the Associates and ‘Story Of The Blues’ by Wah!, I’m talking about the records he’d done with strings on. So it was a no-brainer that we wanted him to do Everything Must Go”.

In 2021, BBC spoke with Manic Street Preachers’ lead, James Dean Bradfield, about A Design for Life. How the song saved the band. It would have been incredibly tense releasing a single from an album that was released after the disappearance of Richey Edwardsd. How it would be received and whether long-term Manic Street Preacher fans would bond with it:

“We were just coming out of our own trauma at that point," Bradfield continues. "Design for Life was proving to be something that kept us going as a band, that validated us, that took us past the procedure of not knowing whether we could be in the Manics any more.

"It kind of solved a lot of really awkward emotional riddles for us. We were on our way to something, reaffirming ourselves and staving off having to think about really serious, damaging things with regards to Richey and his family."

'Snow globe moment'

A Design for Life is what Bradfield describes as a "Trojan horse Manics" tune - using epic radio-friendly rock to carry a political message.

Using similar tactics, they managed to subsequently smuggle If You Tolerate This Your Children Will Be Next and The Masses Against the Classes to the top of the UK singles chart. (The former tackled the Spanish Civil War, while the latter contained quotes from both Noam Chomsky and Albert Camus.)

On their 14th and latest album, their trademark big guitar sound has been largely replaced by Abba-inspired, piano-driven pop melodies. Bradfield, the band's main musical force, learned to play piano properly in lockdown after inheriting one from another Edwards - a 105-year-old Mrs Edwards in Cardiff, external.

"It felt like a special gift being stowed upon us", he says. And he soon began to find new joy in the old chords.

"I had that lovely experience on the piano of just tooling around and going, 'Oh my God, I have to call Billy Joel. If the band don't want this he will!'" he laughs.

A Design for Life for was only narrowly kept off top spot by Mark Morrison's Return of the Mack”.

On 15th April, it will be thirty years since A Design for Life came out. Though it should have reached number one, the fact it was kept off the top of the single chart by Mark Morrison is no shame. However, I do think that A Design for Life is a better song than Return of the Mack. A more important one. Released a month before Everything Must Go, a hugely acclaimed album, this song still stirs the soul and holds this incredible power. 1996 found Manic Street Preachers rebuilding and recalibrating after the disappearance of Richey Edwards. The trio figuring just…

HOW to move on.