FEATURE:

Be Thankful for What You’ve Got

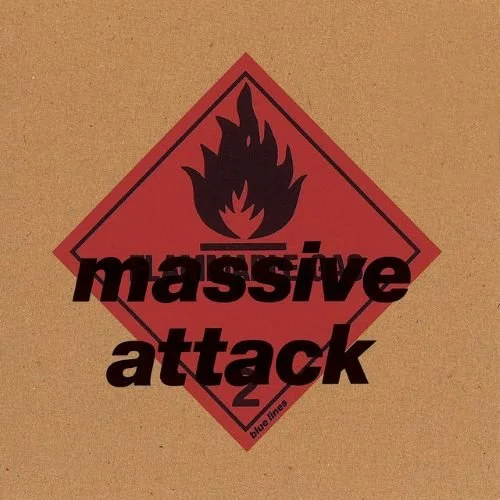

Massive Attack's Blue Lines at Thirty-Five

__________

EVEN if it is not a massive anniversary…

IN THIS PHOTO: Massive Attack (Robert '3D' Del Naja, Grant 'Daddy G' Marshall and Andrew 'Mushroom' Vowles) in June 1991/PHOTO CREDIT: Kevin Cummins/Getty Images

the same way as a thirtieth or fortieth, I think that a thirty-fifth anniversary is still important. That takes me to Massive Attack’s debut album, Blue Lines. Released on 8th April, 1991, it took about eight months for the group to put the album together. Blending genres like Soul, Reggae and Electric, Blue Lines is often simply seen as a Trip-Hop album. I guess it is, though it is so much more than that. Perhaps inspiring other artists like Tricky and Portishead, Blue Lines is one of the most influential albums of the last thirty-five years. Robert ‘3D’ Del Naja, Grant ‘Daddy G’ Marshall, and Andrew ‘Mushroom’ Vowles created a masterpiece with their debut. I previously celebrated thirty-five years of its second single Unfinished Sympathy. Also on Blue Lines is Safe from Harm, Be Thankful for What You’ve Got, and Daydreaming. One Love is perhaps my favourite from the album. A top twenty on the U.K. chart, Blue Lines must go down as one of the best debut albums ever. The Bristol group worked with collaborators such as Shara Nelson and Horace Andy to give the album these different vocal personality and layers. The tracks vary too. One might assume the album to be quite samey in terms of sound, yet Safe from Harm sounds a different beast to One Love or Hymn of the Big Wheel. Prior to its thirty-fifth anniversary, I want to introduce some features about the seismic and staggering Blue Lines. I am starting out with Albumism and their feature from 2021, as they marked thirty years of a classic:

“The origin of Massive Attack dates back to the mid 1980s, when 3D, Daddy G, and Mushroom formed the now-legendary Bristol sound system The Wild Bunch with their kindred musical spirits, including producer Nellee Hooper (Soul II Soul, Björk), DJ Milo Johnson, and Adrian “Tricky” Thaws. Through their shared admiration for graffiti art and various musical styles, downtempo rhythms, and subdued vocals, the collective both embodied and advanced the Bristol underground scene. “[Bristol’s] like a town masquerading as a city, and what it's always been good at is the underground scene, in both art and music,” 3D, a former graffiti artist, told The Telegraph in 2008. “Bands would flourish locally before they reached a national level and because there was never a big media or music industry here, people were doing it for their own gratification. Creativity here never grew in a contrived way, people were just teaching themselves and beating off the competition to become a big fish in a small pond."

From their earliest days to their aforementioned recent recordings, Massive Attack have avoided succumbing to narcissism and the celebrity spotlight, as their mugs have never appeared on any of their albums or singles’ front covers. It would seem, then, that the group prefers for their music, and not their faces, to define their artistic identity whilst preserving their professional integrity. Moreover, their reputation as ambassadors of the so-called Bristol Sound has always seemed to make the group a bit uneasy. “There’s this Bristol myth,” a dismissive 3D insisted during an April 1991 NME interview. “Everyone talks about a Bristol sound, but half our album was done in London and the video for ‘Unfinished Sympathy’ was shot in LA.”

Geographical contextualization aside, Blue Lines, their debut long player from which the masterful “Unfinished Sympathy” originates, was a landmark achievement at the time of its release. Together with Soul II Soul’s Club Classics Vol. One (1989), The KLF’s White Room (1991), LFO’s Frequencies (1991), The Orb’s The Orb's Adventures Beyond the Ultraworld (1991), and Primal Scream’s Screamadelica (1991), Blue Lines proved a vital blueprint for the proliferation of British dance music as the end of the 20th century approached. Its mellifluous mélange of various inspirations characterized by assorted hip-hop breakbeats, expertly selected samples (Billy Cobham, Funkadelic, Al Green, Isaac Hayes, etc.), dense dub rhythms, cerebral rhymes, and soulful guest vocals is unabashedly reverential to the past, but still represents a fresh and novel sound imitated by no one at the time.

Recorded in Bristol and London in 1990 into early 1991 and released on their own Wild Bunch imprint by way of Virgin/Circa, Blue Lines was the outcome not just of Massive Attack’s musical vision, but also a fair amount of coaxing by one of the group’s most devoted champions. “We were lazy Bristol twats,” Daddy G conceded to The Observer in 2004. “It was Neneh Cherry who kicked our arses and got us in the studio. We recorded a lot at her house, in her baby's room. It stank for months and eventually we found a dirty nappy behind a radiator. I was still DJing, but what we were trying to do was create dance music for the head, rather than the feet. I think it's our freshest album, we were at our strongest then.”

Executive produced by Cherry’s musical collaborator and husband, Cameron “Booga Bear” McVey, the album was co-produced by the group and the late Jonny Dollar. (As a side note, due to assumed sensitivities concerning the Persian Gulf War raging at the time of the album's completion and per McVey's urging, the initial pressings of Blue Lines and the "Unfinished Sympathy" single were adorned with the temporarily abbreviated band moniker "Massive." A ceasefire was declared on February 28, 1991, and "Attack" was then reincorporated for all subsequent LP pressings and singles.)

Album opener and third single “Safe From Harm” offers one of the album’s most dramatic and foreboding arrangements, largely built around the sample of the revered jazz fusion composer Billy Cobham’s “Stratus” (1973). The track’s subdued, swirling sonics provide the perfect backdrop for Nelson’s defiant voice to shine, as she vows to protect her “baby” amidst the inevitable madness of the world and convincingly admonishes “if you hurt what's mine / I'll sure as hell retaliate.”

Though Nelson casts a wide spell across Blue Lines, the same can absolutely be said for the prolific, sweet-voiced reggae crooner Horace Andy, who features on three tracks with the geopolitically charged album closer “Hymn of the Big Wheel” the most memorable of the bunch. Andy assumes a paternal tone throughout the track, as he reflects on life (“the wheel”) and the human struggle to preserve one’s innocence in the midst of the world’s destructive forces. He laments the environmental impact of industrialization across the song’s most poignant verse: “We sang about the sun and danced among the trees / And we listened to the whisper of the city on the breeze / Will you cry in the most in a lead-free zone / Down within the shadows where the factories drone / On the surface of the wheel they build another town / And so the green come tumbling down / Yes close your eyes and hold me tight / And I'll show you sunset sometime again.”

Despite its plaintive lyrics, “Hymn of the Big Wheel” concludes with a redemptive refrain, as the sanguine Andy surmises “The ghetto sun will nurture life / and mend my soul sometime again.”

Other standouts include the dubbed-out “Five Man Army,” the slinky groove of the Nelson blessed “Lately,” and slow funk of the title track, which lifts Tom Scott & The L.A. Express’ 1974 single “Sneakin’ in the Back” to great effect. Featuring Tony Bryan on vocals, the group’s cover of William DeVaughn’s 1974 hit “Be Thankful for What You've Got” is faithful to the original—a tad too faithful, perhaps—and easy on the ears, but it’s also the album’s most incongruous moment, largely owing to being the most obviously derivative among Blue Lines’ nine compositions”.

There is a lot written about Blue Lines, so apologies to throw a lot in! Such an important album, I did want to include a few different pieces. This article is one that talks about, among other things, the legacy and impact of Blue Lines. I was seven when the album came out, so perhaps a bit young to remember it. However, in years since, this has become one of my all-time favourites:

“Blue Lines was the work of Massive Attack’s original lineup, with Marshall joined by Robert “3D” Del Naja, Andrew “Mushroom” Vowles and Adrian “Tricky” Thaws, all of whom had previously worked with Bristol-based sound system, The Wild Bunch. However, Blue Lines greatly benefitted from the group’s desire to collaborate, with Jonny Dollar (Gabrielle, Neneh Cherry) co-producing and special guests Shara Nelson and Jamaican reggae icon Horace Andy supplying decisive vocal performances on the record’s key tracks.

Indeed, it’s fair to say both vocalists excelled themselves on Blue Lines. Andy turned in superb performances on the redemptive “Hymn Of The Big Wheel” and an uplifting cover of William Vaughan’s 1972 soul classic “Be Thankful For What You Got,” while Nelson arguably stole the show with her contributions to the album’s twin peaks, “Safe From Harm” and “Unfinished Sympathy.” Featuring neatly-spliced Funkadelic and Herbie Hancock samples, the former made for a compelling listen, but it was “Unfinished Sympathy” which really set Blue Lines apart. Enveloped by a glorious, cascading string arrangement and topped off by Nelson’s soaring, soul-searching vocal, the song was a widescreen pop classic and its U.K. chart peak of No. 13 brokered Massive Attack’s mainstream breakthrough.

With “Unfinished Sympathy” also going Top 20 in several European territories, Blue Lines did brisk business on the charts, rising to a peak of No. 13 and eventually going double platinum in the U.K. In the long run, though, its critical cachet has vastly outstripped its commercial returns.

Rolling Stone went on to declare that Blue Lines was “the blueprint for trip-hop” – the genre-tag later applied to like-minded 90s classic such as Tricky’s solo debut Maxinquaye and Dummy by fellow Bristolians Portishead – and the album is still regularly cited for its role in shepherding dance music into more introspective realms. “On its release, Blue Lines felt like nothing else,” The Guardian’s Alex Petridis wrote in a 2012 retrospective. “But it still sounds unique, which is remarkable given how omnipresent trip-hop was to become.”

“I was still DJ-ing when we made Blue Lines, but what we were trying to do with it was create dance music for the head rather than the feet,” Daddy G reflected in an interview with The Observer in 2013. “I still think it’s our freshest album”.

Prior to ending with a review from Pitchfork, there are a couple more features I want to get to. In 2012, The Guardian focused on the remastered edition of Blue Lines. They write how “In 1991 the laidback Bristol collective roused themselves to unleash their debut album. Reissued 21 years on it remains a landmark. Here, an early champion of the band recalls its making and its lasting influence”. Sean O’Hagan shares why Blue Lines is so important to him – and why it made such an impact:

“With the release of Blue Lines in 1991, Massive Attack were on a creative roll but seemed unaware of their impact or the shape of their future. I accompanied the group to Jamaica in early 1992 to write a feature for the Guardian around the filming of the Dick Jewell-directed video for their planned fifth single, Hymn of the Big Wheel, which featured the veteran reggae singer Horace Andy on lead vocals. In between filming, we visited Studio One, met the great reggae rhythm section Sly and Robbie, bought dozens of old and new reggae 45s, went to Prince Jammy's studio, crossed the hills to Ocho Rios, were held up by armed men at a roadblock and bonded over Appleton's rum and the inevitable bags of Jamaican spliff. Despite a budget of around 60 grand, no video ever appeared.

I met them, again, at the filming of another Baillie Walsh video for Be Thankful for What You've Got, which consisted of a stripper doing her act while miming the song in Raymond's Revue Bar in Soho, London. I sat with the group in the darkened auditorium, wondering what their role in the video was. They did not have one – unless you count the glimpse of a few shadowy figures exiting the strip club towards the end of the act. You can now see the video online but, unsurprisingly, it was never shown on MTV or the BBC. The group seemed unconcerned by these setbacks. They moved to their own unpredictable beat, so much so that I would not have put money on them still being with us today, so laidback was their attitude, so lackadaisical their work rate, so uninterested were they in press or promotion. But Massive Attack, against all the odds, are now seasoned survivors.

They are not, though, the Massive Attack that made Blue Lines. Tricky departed amid some rancour not long after the release of the album, as did Shara Nelson, their first and greatest singer, both claiming they had not been given enough recognition for their contributions to the Massive Attack sound. Since his extraordinary debut, Maxinquaye, Tricky has followed his own increasingly erratic path, while in a sad development Shara Nelson became deeply troubled and was last year given a 12-month community order for persistent harassment of the Radio 1 DJ Pete Tong, whom she claimed was her husband and the father of her child.

Other great guest vocalists worked with the group following Nelson's departure, beginning with Tracey Thorn on the title track of the group's equally brilliant second album, Protection, and erstwhile Cocteau Twin Liz Fraser on the hypnotic Teardrop from their third album, Mezzanine. Then Massive Attack splintered again when Mushroom, the great oddball musical genius behind those albums, departed for reasons that remain clouded in mystery but probably had something to do with the smalltown claustrophobia of the Bristol scene and the inevitable clashes of ego and direction that beset all great groups at some time or another. (I spoke to him by phone a few times last year when he was finishing his long-anticipated solo album but have not heard from him since. He seemed in good spirits.)

Massive Attack endure in the form of 3D, Daddy G and a proper group playing proper instruments that accompanies them when they play live. The collective ethos has been abandoned for something more rigid and functional.

The original idea that was Massive Attack – the collective, elastic, shape-shifting but essentially tight-knit, identity that helped make Blue Lines such a groundbreaking album has long since evaporated. The album, in all its newly polished glory, remains: a testament to a time when their vision was a truly collective one that challenged the notion of the pop group as well as the pop song. It still seems odd to me that the lumpen, guitar-fuelled Britpop years followed its release, the old order re-establishing itself in the most conservative fashion as if Blue Lines had never happened. Twenty-one years on, those guitars still sound old and all too familiar. Blue Lines, though, is like a blueprint for a different kind of pop future: stranger, richer, day-dreamier”.

Lets move on to PopMatters and their informative and illuminating feature. 1991 was a year where more than a few classics were released – including Nirvana’s Nevermind -, but there was something about Blue Lines that meant it created more of an impression than most of the best from that year. In terms of creating this movement or filling a void:

“Yet, while on the whole Blue Lines serves to uplift (swimming in sunshine, buoyed by the joys of its musical touchstones, along with the sweetening vocals of Shara Nelson and Horace Andy), as reportage the album often plumbs dark depths. Braggadocio aside, rap is fundamentally personal in comparison to pop’s clichéd prose. Yet for affecting a more intimate, sometimes almost whispered tone, Massive Attack brought rap in closer, transforming it to become inner-voice — in turn, revealing its men to be seemingly unsure of themselves at heart. Around every party and opened-top car cruise, the creeping fug of reefer-paranoia edges: the downside of free-living. Tempers are barely contained, lovers risk a beating for eggshells stepped on, and the nagging sense that drifting days spent out of work and in pursuit of local peer respect will eventually lead to undoing.

Musically, Massive Attack did more than echo dub; they built by its rules. For dub is all about space within the mix, allowing the rhythms and undulations of its repeats to reverberate. After all, dub is the music of — to quote from the group’s second album, Protection — “Jamaican aroma”, and stress and clutter just won’t do. So, while reggae’s influence is blatant on “One Love”, check out “Five Man Army” or the title track, where that genre’s defining rule — and one of music’s abiding truths — that’s it’s often what you don’t play that counts, holds sway.

As with classic hip-hop, Blue Lines indulged in sampling — those often mysterious, sometimes playful musical quotes and references; covert nods to those in the know. Piratical treasures, it would be impossible to secrete in our Google age, seemingly mapped free of the unknowable. More so, for the simple fact that, eight short months after Blue Lines, the landmark Grand Upright v. Warner copyright case made it law to seek pre-release clearance for — and therefore opened the door to huge fees payable on — sample use, which effectively priced samples beyond most acts’ recording budgets.

However, for all its underground thought and means, it cannot be overlooked that Blue Lines also marked a commercial shift in the relationship between dance music and the mainstream music industry. Previous to mid-1991, dance music had proven steadfastly immune to major label advances, instead choosing to run itself. Newly-affordable bedroom samplers and the role of handy backstreet vinyl-pressing shops (let alone the lax state of copyright laws) kept dance creatively nimble, self-produced, and (borderline trunk-of-the-car) independently distributed. All of which served to render it — irritatingly, for the majors — utterly self-sufficient.

Furthermore, dance music had always been about the 12″ single, not the preferred, higher mark-up, industry format of choice — the album. So when Blue Lines proved (along with Unknown Territory by Bomb the Bass and Seal’s first album, all released within months of each other) that dance music could if given the opportunity, creatively handle — but more importantly, sell — albums, the major labels were across the dance-floor in a shot. In short, no Blue Lines: no Leftfield, Chemical Brothers or Portishead’s Dummy. Fat of the Land by the Prodigy couldn’t have happened; Bjork’s Debut wouldn’t have come to pass. And it’s doubtful Norman Cook’s Fatboy Slim guise would have championed.

Looking back, it’s hard to fathom Blue Lines is 29 years old, simply because it remains relevant. 3D’s stencil-based sleeve-art still resonates; its nods to and progressive riffs on street-graffiti did much to legitimize that hotly-contested art-form, bridging the street-gallery divide over which Banksy would later cross. Furthermore, sonically, the album has yet to age, in the same weird way classics from any decade refuse to. Partially because the influence of dance and hip-hop still reverberates in our pop palettes two decades on; if not stylistically, then for modern pop production’s insistence on a heavy bottom-end — the rattling bass kick and boom of that distant Jamaican sound-system — which mainstream records lacked previously.

Granted, the album’s deployment of rap draws a line in history, previous to which it could never have emerged. Yet Blue Lines is timeless stuff. Massive Attack smartly pondered beyond that which rap, sadly, became too much about — the easy sway of machismo–in favor of life’s eternal concerns: doubt, sadness and the warmth of smiles; weakness and strength — and love. The same record-like cycles we all revolve through, but can never resolve; the conundrums to which great music becomes our antidote, the soothing balm — our accompaniment for the road.

As Oscar Wilde once assessed, “The moment you think you understand a great work of art, it’s dead for you.” To which, I can only conclude: long may Blue Lines mystify”.

I am going to end with Pitchfork and their positive review for Blue Lines. I do wonder if there will be any special celebration around its thirty-fifth anniversary. Massive Attack would go on to release other genius albums. I still think that their debut is their best offering. Such an incredibly powerful album. Not knowing much about the group, you are not sure what to expect from Blue Lines. It definitely created shockwaves in 1991:

“When Massive Attack first arrived, hip-hop in the UK was still figuring itself out. For years the scene there, such as it was, focused mainly on reproducing trends that had already fallen out of fashion by the time they made it across the Atlantic. That lack of identity was probably an asset for Massive Attack. They didn't have to compete against their contemporaries to see who could sample which Jimmy Castor Bunch break first, or worry about conforming to any outsider whose preconceptions about hip-hop authenticity might not include prog-rock samples or a lush chill-out anthem like "Unfinished Sympathy". Another asset was Neneh Cherry, whose Raw Like Sushi, which Del Naja and Vowles worked on, provided a genre-bending inspiration for Blue Lines, as well as a bankroll to record it. (Cherry even paid the group a salary and let them turn her kid's bedroom into an impromptu studio.)

In fact, those Raw Like Sushi credits (Vowles' for programming, Del Naja's for co-writing "Manchild") were the only real music-industry bona fides any of the principal contributors to Blue Lines had going into it, aside from vocalists Shara Nelson and roots reggae veteran Horace Andy. But somehow the group realized a remarkable and seamless sonic identity. That's clear from the arresting opener "Safe From Harm", which spins an aggressive drumbeat, Del Naja's rap, Nelson's soulful vocals, and a mist of sustained minor-key synths around an intimidatingly muscular bass loop. From that moment, every major part of the Massive Attack profile is already present, from the collaging of genres to the spacious, nocturnal sonic environment to the heavy dose of paranoia that permeates it all.

They spend the rest of the album exploring variations on these themes. "One Love," with Andy on vocals, has a digital dancehall feel, a creepy-funky electric piano riff, and a scratched sample of a blaring horn section that predates Pharoahe Monch's "Simon Says" by almost a decade. "Daydreaming", with its scratchy breakbeat drums, is more directly hip-hop than most of the rest of the album, but the layers of atmospheric synthesizers and Tricky's felonious near-whisper make it clear that Massive Attack was up to something entirely different from what every other rap producer at the time was doing.

Blue Lines brought producers around to its unique vision. By the time Massive Attack released Protection three years later, the group's renegade approach had been copied enough times to become a full-on movement. They'd go on to produce their masterpiece, Mezzanine, a couple of years after, but by then the project had already started to splinter. Tricky split from the collective after Protection to follow his own solo vision, while the core trio behind it would eventually burn out acrimoniously, with Vowles and then Marshall leaving Del Naja to produce increasingly less rewarding music under the group's name. Meanwhile, trip-hop in general had its edges polished off by genteel musicians who transformed it into soundtracks for fashionable hotel lobbies.

Still, that doesn't change the fact that Blue Lines was a startling record when it came out, and it remains one now. For this reissue it received a new mix and a new mastering job straight from the original tapes. It's available as a CD, in digital form in standard and high fidelity formats, and as a set of two LPs and a DVD of high resolution audio files. There aren't any bonus tracks, and aside from a reproduction promo poster in the vinyl edition there aren't any add-ons either. Frankly they'd just be a distraction from the underlying theme that becomes clear once you get absorbed into the music, which is that Blue Lines is still Blue Lines, and most of the world is still trying to catch up to it”.

On 8th April, it will be thirty-five years since Massive Attack’s Blue Lines came out. One of the best albums of all time, it is seen as landmark moment in music history. There are features such as this and this that provides even more detail and insight. Go and listen to this album in full and immerse yourself in its glory. One of those listening experiences you will not forget, Blue Lines has not aged and still reveals something new. You do not hear many Trip-Hop albums today, though I do feel artists need to nod more to Massive Attack and Blue Lines. It is a masterpiece that…

HAS the test of time.